Promise Park Project [Research Showcase]

- Date: Nov. 1, 2014 to Jan. 11, 2015

- Venue: Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

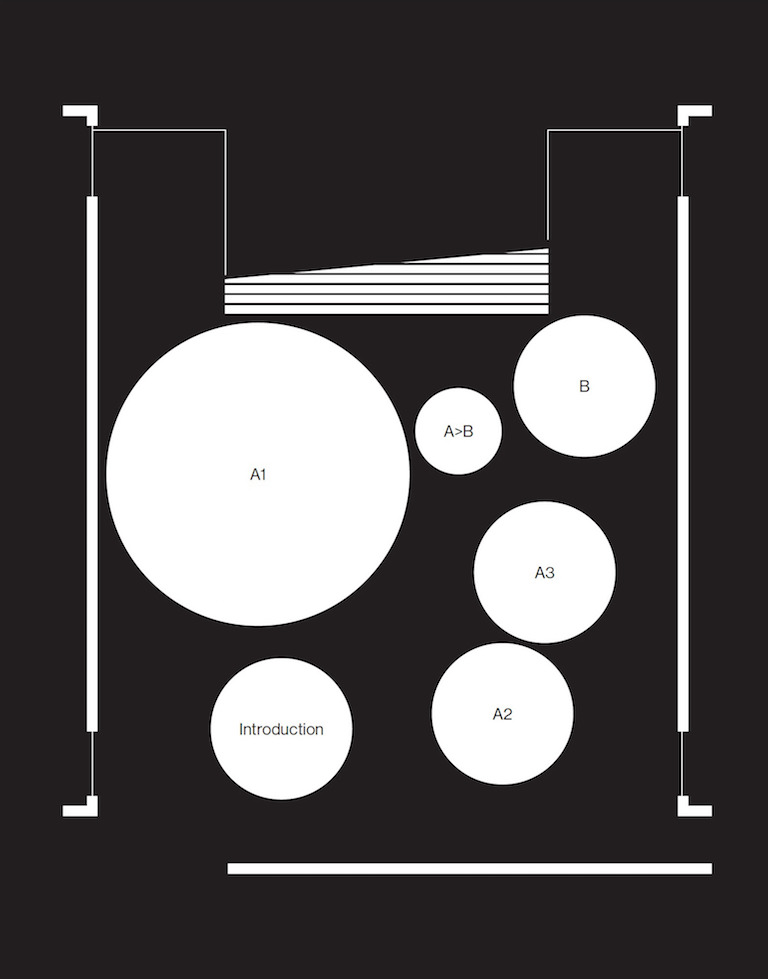

Responding to the “Promise Park” that MOON unveiled in 2013, the YCAM staff has been conducting research together with invited guest researchers of respective fields such as cultural history, folklore, art history, media and architectural history, with the aim to find clues for discussing possible forms of parks in the future. The results were then presented in the form of a research showcase exhibition. In the archive part (section A1, A2, A3), we introduce three different historical cases of Cultural History, Folklore, Architectural History, Art History, and Media History, are referenced for consideration of future parks. In addition to texts and other materials, a system using virtual reality (VR) technology for translating the results of studies and investigations into sensuously experienceable imagery, and other basic technologies that had been previously developed by the YCAM InterLab, were introduced during the exhibition period in demonstrations by members of the InterLab (section B).

A1

St 1.0 – From «Niwa» Stone to Park

Our first case shall explore the genealogy of the ancient Japanese “park-like” space, focusing on the “stones” seen in gardens (“Niwa”), usually perceived as the origin of parks, and also in various natural or urban spaces. Mankind has always created ideal natural scenery in an enclosed space, the garden. And at the very core of garden making is the setting of stones. The setting of stones could be traced back to the stone circles in the Jomon period (c.12,000 B.C. – 300 B.C.) created at the heart of settlements as ritual sites and public cemeteries. The stone arrangements had an intense relationship with the surrounding mountains and the celestial movements. By contrast, boundary spaces like Tsuji, or crossroads, were ancient Japanese open spaces, where people came and went and trades, performing arts and fortune telling took place. Stones were placed to protect these spaces, prevent the invasion of evil, and were worshipped as deities assuring family and business prosperity. Taking these into consideration, Presentation 1 (“Erected Stones and Surrounding Mountains”) would situate gardens and stone circles on the same context and propose a system exploring the relationship between the stone arrangements in such locations and the surrounding mountains. Presentation 2 (“Archive of Stones in Yamaguchi City”) would present the result of fieldworks conducted on various stones in Yamaguchi City, as a means of further microscopic approach towards the involvement of stones in people’s lives.

A2

The Millennium Village Project

As the second example, “The Millennium Village Project” runs organizational activities such as Norihito Nakatani Seminar (Architectural History) at Waseda University, Tsuyoshi Kinoshita Seminar (Landscape Architecture) at Chiba University, and Shigeatsu Shimizu Seminar (Architectural History) at Kyoto Institute of Technology participate. “The Millennium Village” are villages and areas that are older than 1,000 years which survived through several natural disasters and changes, and produced a social fabric based on certain ways of living and working while maintaining the same geography. “The Millennium Village Project” is the platform for research and study and it’s run voluntarily by researchers who carry out tasks on architecture history, architectural design, landscape architecture, social and environmental engineering, landscape and civic design, folklore, historic geography, and web design. The website discloses the research process by publishing the millennium village on the map including detailed research examples such as geological maps, aerial photographs, and simplified maps. At the exhibition, images taken from the sky above the millennium village will be published. Analyzing villages that survived more than 1,000 years can be a hint to predict the way communities would be in 1,000 years time.

A3

Re-trace Central Park in New York in 1973

The third case study involved a historical review and analysis of New York’s Manhattan Island, which is regarded as a leading-edge example of a modern, man-made city, and Central Park, the pseudo-natural space to which it is home. Seeking to consider the relationship between the natural environment and humans, which continues to change at a dizzying pace, the artist Robert Smithson wrote an essay about Central Park, which is a park in an urban society. Central Park is an urban park in New York that was designed by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, among others, in the latter half of the 19th century, a time of remarkable population growth. Olmsted is said to have designed the park after studying the effects that the glacial period several million years earlier had had on topography. Smithson demonstrated an interest in deposition, which is a constant process of change, regarding Central Park as a place where environmental change and anthropogenic intervention intersected, having been designed through this process. Furthermore, first-person reportage has been used to understand parks in terms of their value as spaces for living. Based on Smithson’s essay, this case study traced back the ideas of both Olmsted and Smithson and interpreted changes in terrain, environmental change, changes in the activities of the humans within that environment, and shifts in urban spaces as well as a “park” as the product of these elements in terms of both its temporal and spatial aspects.

Connecting A to B

Fine Art History and Park in the Air / Drifting Space

A profusion of different examples of parks can be found throughout art history. This part examines the perspectives on the world with which the symbolism and singular nature of parks as “enclosed spaces and an act of enclosure” are associated in artistic expression. To start with, we can see that throughout the history of civilization, regardless of era or culture, parks have, via gardens, been associated at a fundamental level with some kind of paradise (utopia) separate from life here on Earth. By creating an enclosed sphere, parks, while remaining public spaces, could be regarded as entities that differentiate themselves from the surrounding external environment or context, giving rise in the space within to a sense of the imaginary or saltatory that transforms sight lines and perceptions. What are the boundaries of images separating “the park” from “outside the park”? This task will identify the multi-layered phenomenon that arises from the act of delineating the framework that a park constitutes by taking leaps into works of art. Alternatively, the connections between one park and another, and the multiplying chain of nested networks of park-like spaces outside parks could well come to have a strong significance in artistic imagination.

B

Future Part: Future Sense–Boundary between mankind and technique

“Future park” is not immune to the changes in the boundary between communities and individuals, mankind and technologies through technical innovation. A future society is already coming about. In this kind of society, people will have wearable computers as a part of our body to connect to the network any times, artificial intelligence will communicate with others like a human. It can be said that people’s consciousness will lose the boundary between reality and data. Moreover, through the innovation of bio technology, such as data sensing of heartbeat, myoelectric, and brain waves, and such as cloning technology and gene modification. By these innovations,living creatures other than humans, such as animals and plants,are connecting to engineering technologies seamlessly.

The significant integration and development of these technologies and network society would create new boundaries beyond imagination while almost eliminating the boundaries between mankind and technologies. Under these circumstances, we consider how park connect the public and individuals in urban spaces and such as a possibility of that human can internalize a “park” or not, are discussed through introducing technologies developed by YCAM InterLab.