If you travel about 3 km southeast of the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM), along the Niho River, and then head up into the ravine to the north, you will find a Tendai sect temple called Hikamisan Kōryūji. Today, all that remain are a few tiny buildings among the fields and houses, and it seems to have hardly any functions as a temple at all anymore. However, this temple was founded in the year 611 by Prince Imseong (Rinshō Taishi), the ancestor of the Ōuchi clan. It is said to have become the clan’s tutelary temple and shrine once Myōkensha Shrine was built in its precincts in around 827, forming an extensive complex of buildings that embodied the syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism.

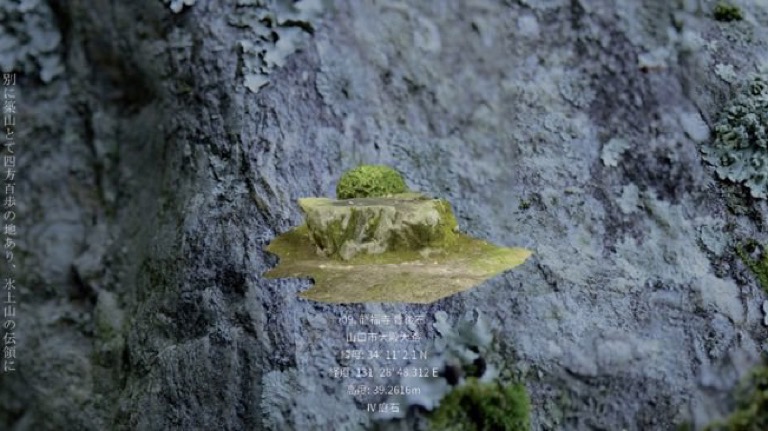

Although another building now stands on the site of the Kōryūji sub-temple once called Jōrakubō, careful scrutiny of one of the stone walls separating the garden from a field reveals the character “ri (理)” carved into a stone. (Fig. 1) Another of the stones in the garden of that building is engraved with the characters “myōji (名字).” (Fig. 2) If you climb 600 m north from there further up Mount Hikami, you will reach the old site of the main building of Myōkensha Shrine’s upper shrine; a stone bearing the characters “bunshin (分眞)” has been solemnly placed on the central stone platform. (Fig. 3) This clearing amid the dense vegetation of the mountain forest is plain for all to see and the “bunshin” stone towering above the stone platform is swathed in a mystical ambience.

It is said that these three unusual stones were once stones called Rokusoku stones (六即石, literally six Soku stones) that were repurposed. *1 The following passage appears in the latter volume of the Hikamisan Hiōki (The Secrets of Mount Hikami), a book about this temple composed in 1750.

*1. Takayuki Maki, “Suōkoku Hikamisan Kōryūji no keidai to sono dōsha haichi,” in Yamaguchi Daigaku Bungaku-kaishi (Yamaguchi: Yamaguchi Daigaku Bungakukai, 2015), pp.49-50.

The origins of the Rokusoku stones. The distance from the Hōkai-mon Gate to the main hall was six chō, so Rokusoku stones were erected on the basis of the 42 stages and six steps. Stones for “ 下乗” or “ 下馬” (instructing people to alight from their dismount from their horse there) are said to have been modeled on those at Rinnōji Temple (also known as Nikkō-san). All of the stones were erected by Gyōkai, the monk who restored Kōryūji Temple. *2

*2. Takayuki Maki, “Hikamisan Hiōki honkoku narabini kaidai (2),” in Yamaguchi gaku no kōchiku (‘Yamaguchigaku’ kōchiku purojekuto, 2008), p.87.

Kōryūji Temple’s precincts were laid out ascending from south to north, with stones called Rokusoku stones erected every chō (approx. 109 m) along the six-chō approach path from the entrance at the southern Hōkai-mon Gate to the main hall to the north. Along with the stones instructing visitors to alight from their dismount from their horse, these Rokusoku stones are said to have been erected by the monk Gyōkai, who restored Kōryūji Temple in the latter half of the 17th century.

The “Rokusoku” are the six steps that the Tendai school of Buddhism taught were required to reach the ultimate satori, or enlightenment: “Risoku (理即),” “Myōjisoku (名字即),” “Kangyōsoku (観行即),” “Sōjisoku (相似即),” “Bunshinsoku (分真即),” and “Kukyōsoku (究竟即).” The “42 stages” are the 42 stages that a bodhisattva must go through to reach the level of enlightenment of the Buddha. By placing six stones along the path from south to north, Gyōkai likened it to the six-step path leading to ultimate enlightenment. As far as I have been able to ascertain, there are no other examples of stones, etc. being used to render the Rokusoku steps in real-life spaces in this way.

Three of these Rokusoku stones are today being used for alternative purposes in unusual ways, as seen above. In particular, the Bunshin stone was, until recently, believed to signify the “alter egos” of the gods. *3 The remaining stones (“Kangyō,” “Sōji,” and “Kukyō”) have not been found. These stones once provided a visible reminder, in a real space, of the six steps to ultimate enlightenment. Three of the stones have been repurposed in an extraordinary way, while the other three have been lost to us. Perhaps they can lead us along the path to learning some kind of lesson.

*3. Takayuki Maki, “Suōkoku Hikamisan Kōryūji no keidai to sono dōsha haich,” p.50.

1.

Etymologically speaking, the word “park” means “an enclosed place” and was used in particular to indicate a royal hunting ground. These went on to become places open to the public, so the word “park” acquired the meaning with which we are familiar today, signifying a public park. The word “garden,” which is strongly associated with parks, has a similar etymology, but, to put it in somewhat simplified terms, whereas a garden can be described as purely a private space for a privileged class, a park is a public space open to the common people.

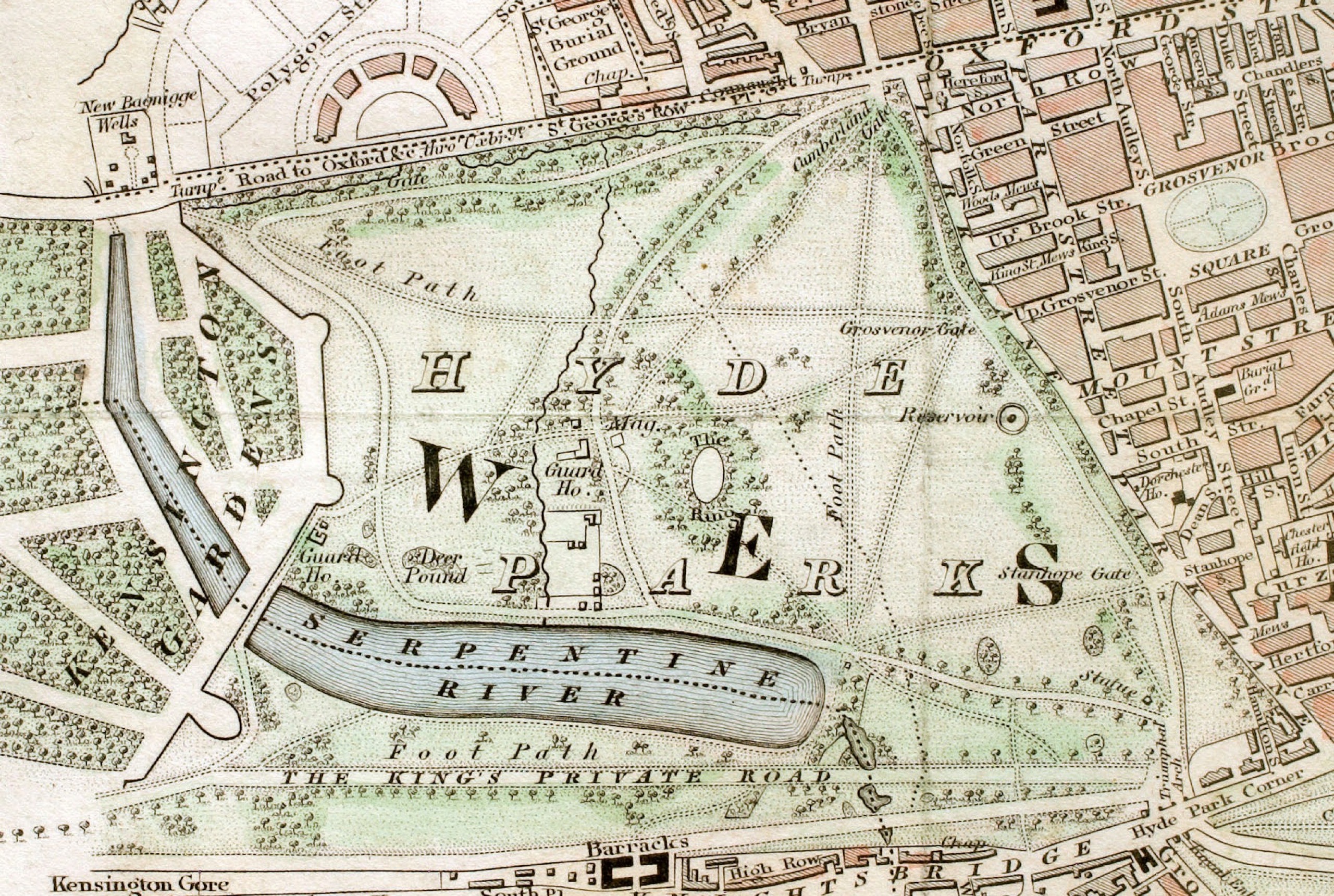

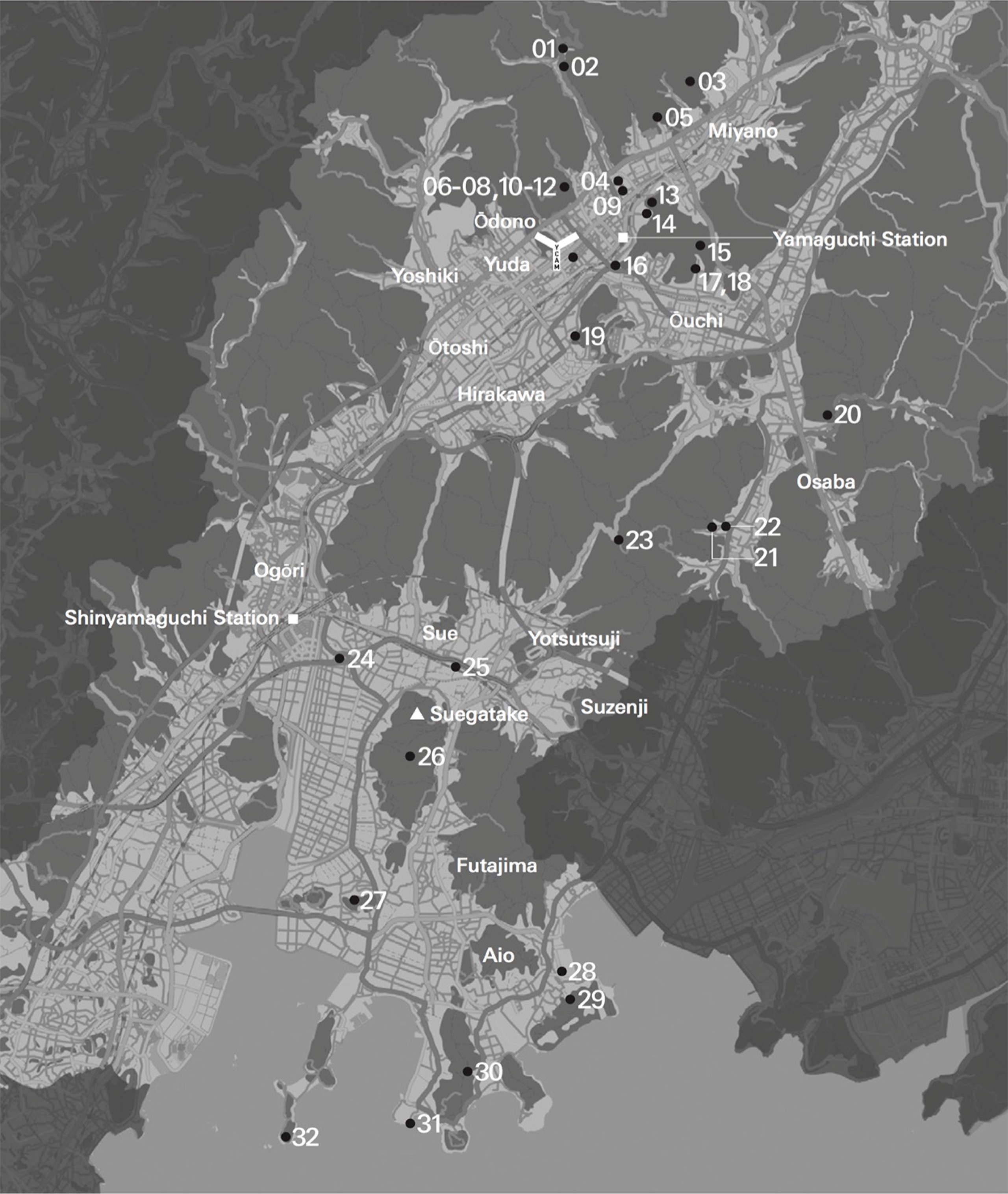

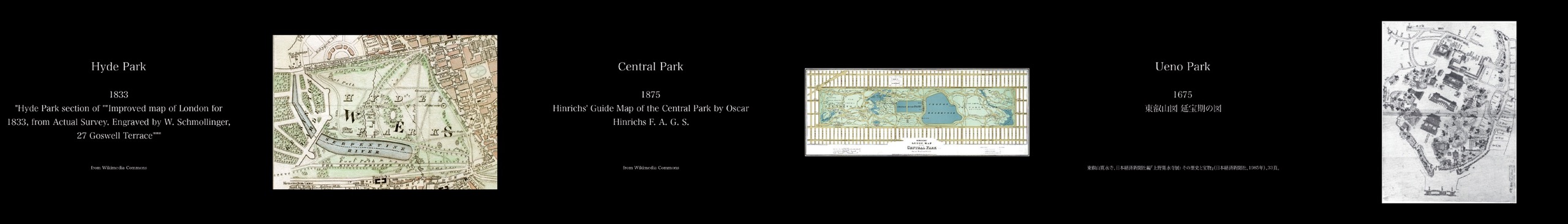

The world’s first park is said to be Hyde Park in London, UK. The land on which Hyde Park stands originally belonged to Westminster Abbey, but it was confiscated by Henry VIII in 1536 and became a royal hunting ground. However, Charles I opened this hunting ground to the public in 1637, temporarily creating the world’s first public park. Thereafter, Hyde Park was repeatedly closed and reopened as political regimes came and went; the activities that the park hosted over the centuries were many and varied, including sporting events and military parades. At the same time, Hyde Park underwent a series of changes wrought by various people: in the 18th century, at the instigation of Queen Caroline, the world’s first man-made lake, the Serpentine, was created there, giving the park the appearance of a typical English landscape garden; then, in the 1820s, further development was carried out to a design by the architect Decimus Burton (1800-81), giving it the layout that remains more or less unchanged today. (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4. Hyde Park (1833)

Amid the rapid population rise and environmental degradation resulting from the expansion of cities in the early 19th century, in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, public parks came to be regarded as playing a crucial role as “the lungs of the city.” Thus, having been pioneered with Hyde Park, the modern park was formed.

One of the key events in the history of Hyde Park came in 1851, when the Crystal Palace ─ said to have blazed a trail for modern architecture ─ was built to host the world’s first Universal Exposition. (Fig. 5) This immense, breathtaking structure was built from around 4,500 tons of iron and about 300,000 sheets of glass; it measured about 563 m (1,851 feet) long and around 124 m wide, and the top of its dome towered approximately 33 m above the ground. The exhibits from 34 countries around the world numbered in excess of 100,000, categorized as raw materials, machinery, manufacture, and plastic arts. A total of approximately 6.04 million people visited the Great Exhibition over the 141 days for which it was open between May and October.

Fig. 5. Crystal Palace (1851)

Joseph Paxton (1803-65), who designed the Crystal Palace, was originally a gardener, rather than a highly trained architect. Aiming to improve greenhouses for the purpose of plant research, he created a new, larger kind of greenhouse from glass, iron, and wood at Chatsworth, and the Crystal Palace was simply an even more gigantic version of this.

From time immemorial, various plants have been grown in gardens worldwide. For example, in ancient China during the Han dynasty, Shanglin Park is said to have had 123 km in circumference or 139 km square and to have contained countless rare plants. Greenhouses are structures that enable plants that do not ordinarily grow in a particular area to thrive in a garden, by creating a different climatic environment from the natural one there. This made it possible for an even more diverse array of plants to be cultivated in gardens; the construction of the Crystal Palace, which evolved from these greenhouses, provided a venue for showcasing not only plants and other products of nature, but also man-made objects from across the globe. All of these were nothing less than “the fruits of the imperialist gaze seeking to colonize the world,” as described by Shunya Yoshimi. *4

The Crystal Palace was dismantled as originally planned once the Great Exhibition ended and the proceeds of the event were used to purchase land in South Kensington, a little way south of Hyde Park. This is, in fact, the land on which a cluster of cultural facilities stands today, among them the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Natural History Museum. *5

The 1851 Universal Exposition established a pattern that other countries followed when they held the Universal Exposition: the construction of a huge building in a park. As such, it would be fair to say that, as well as being places where a wide variety of different things coexist, parks are, by virtue of the fact that they are open to everyone, a kind of matrix that enables people to come into contact with those things. coexist, parks are, by virtue of the fact that they are open to everyone, a kind of matrix that enables people to come into contact with those things.

*4. Shunya Yoshimi, Hakurankai no seijigaku: Manazashi no kindai (Tokyo: Kōdansha, 2010), p.46.

*5. A second Universal Exposition was held in South Kensington in 1862. The Crystal Palace was then rebuilt in the south London suburb of Sydenham, serving as a larger cultural complex, but it was destroyed by fire in 1936 and the site where it stood is now Crystal Palace Park.

2.

The system of public parks was instituted in Japan around the time of the Westernization movement during the Meiji period. Asakusa Park, Shiba Park, Fukagawa Park, and Asukayama Park were the first to be opened as a result of the 1873 promulgation of Great Council of State Decree No. 16, which dealt with the establishment of public parks. Ueno Park was opened slightly later, in 1876. The key point is that these parks had all previously been part of the grounds of a temple or shrine, or a notable beauty spot, namely Sensōji Temple, Zōjōji Temple, Tomioka Hachimangū Shrine, Asukayama, and Kan’eiji Temple, respectively. Many public parks were created thereafter, most of which were, similarly, places that had originally been “park-like” spaces in pre-modern times or the gardens of feudal lords that had been opened to the public. It was only in 1903 that the first park created from scratch opened: Hibiya Park, which was Japan’s first western-style park.

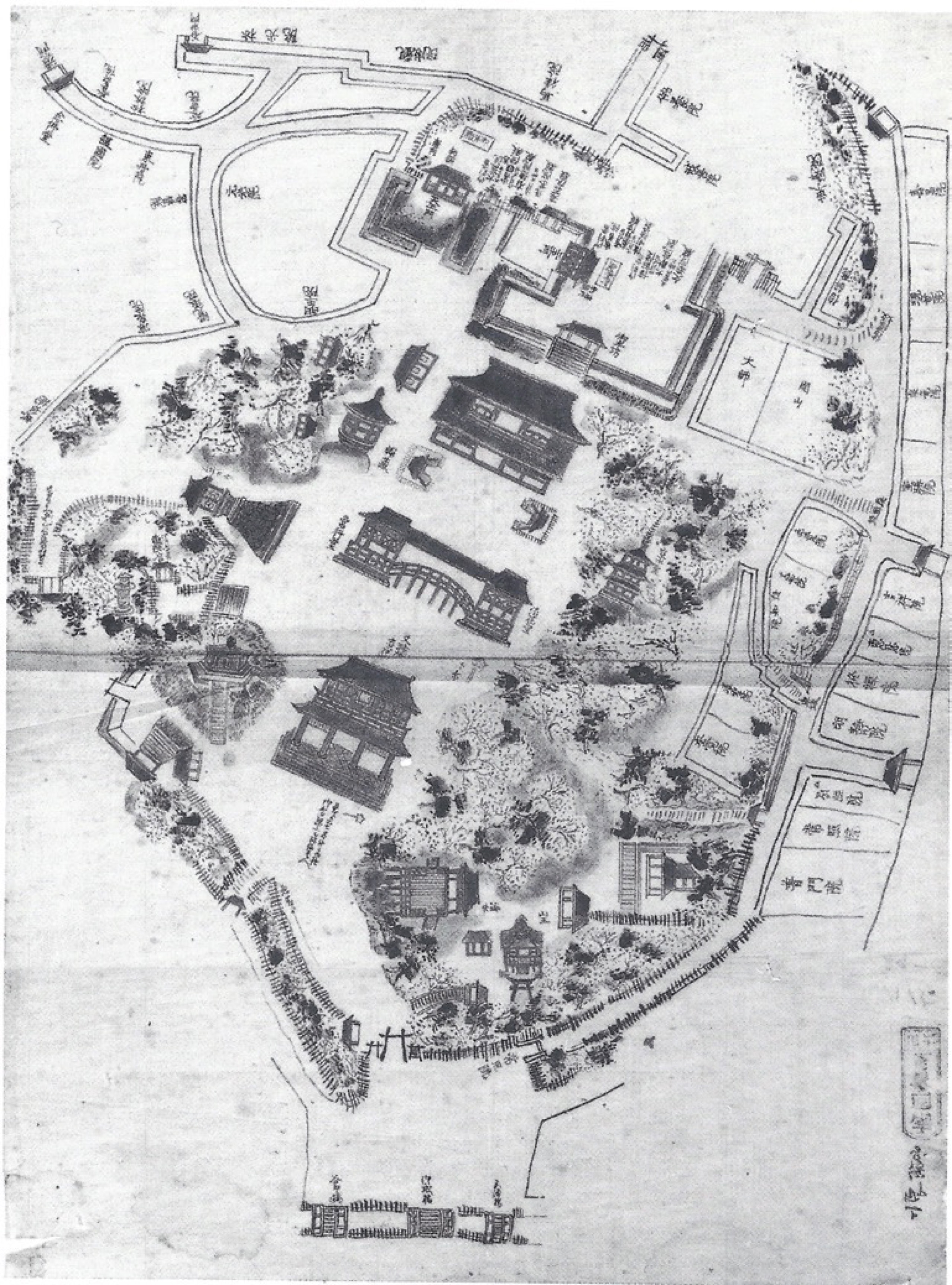

Today, Ueno Park covers an area of approximately 534,000 m2; all of this huge area of land fell within the boundaries of Tōeizan Kan’eiji Temple during the Edo period. (Fig. 6) Kan’eiji is a Tendai sect temple founded in 1625 by the high-ranking priest Tenkai. Modeled on Hieizan (Mount Hiei) Enryakuji Temple in Kyoto, it was, just like Enryakuji, built in the northeast of the city ─ that is to say, the corner from which evil spirits were traditionally believed to enter ─ to serve as the “kimon” (demon gate) for Edo Castle (today’s site of Imperial Palace), in order to protect the castle, as the heart of the city, and therefore the nation as a whole. Shinobazu Pond, in the southwest of the land of Kan’eiji, corresponds to Lake Biwa, as seen to the east from Mount Hiei, and the Buddhist goddess Benzaiten is enshrined on the pond’s Nakanoshima Island, just as she is on Chikubu Island in Lake Biwa. Kiyomizu Kannondō Temple, which faces the pond, equates to Kyoto’s Kiyomizudera Temple. Later, Kan’eiji also served as the family temple of the shogunal branch of the Tokugawa clan and, in its heyday, was a magnificent complex symbolizing the prestige of the Tokugawa shogunate, with around 30 halls and stupas and as many as 36 sub-temples. It was around this time that a large number of Yoshino cherry trees were planted in the precincts of the temple and it became a popular spot for the common people to gather to view the cherry blossom, a tradition that survives there today.

Fig. 6. Map of Kan’eiji Temple (1675)

However, in 1868, amid the upheaval that accompanied the transition from the old regime to the new government, virtually the whole of Kan’eiji and its grounds were reduced to ashes during the Battle of Ueno, when the new government’s army ─ led by Masujirō Ōmura, who was from Suzenji in Yamaguchi City ─ quashed the Shō gitai (a group of former Tokugawa retainers). (Fig. 7) Thereafter, Kan’eiji’s boundaries were reduced substantially and, after various twists and turns in the development of the remaining land, it ultimately became Ueno Park.

Fig. 7. Ruin of Kan’eiji Temple (1868)

Since its opening, Ueno Park has served as a key venue for expositions and other national events. In 1873, the Japanese government embarked for the first time on full-scale participation in a Universal Exposition, taking part in the event held in Vienna’s Prater park, with a view to holding an exposition in Japan at a later date. Another goal of its participation was the establishment of museums similar to those in South Kensington in due course.

Japan’s first exposition, the First National Industrial Exhibition, was held in 1877; the galleries and museums that housed the exhibits were built on the site of Kan’eiji’s main temple, while the temple’s inner gate, which had escaped the fire, was used as the main entrance. The event featured around 84,000 exhibits, attracting 450,000 visitors over its 102-day duration. Ueno Park continued to be used frequently for expositions thereafter, including for the Second National Industrial Exhibition, in 1881. Today, the southwest-facing Tokyo National Museum is an imposing presence in Ueno Park; this is none other than the successor to the exhibition venue built on the site of Kan’eiji’s main temple, while the garden and pond at its rear date back to Kan’eiji’s heyday. The fountains in front of the museum accentuate the building’s axis of orientation toward Shinobazu Pond’s Nakanoshima Island, an axis that remains unchanged since Kan’eiji was a commanding presence, stretching toward the main keep of Edo Castle. Ueno Park was gifted to the city of Tokyo by the Imperial Household Department in 1924, on condition that no buildings were erected in front of the museum and that the axis of orientation that had existed since Kan’eiji was built was preserved. *6

*6. Ryōhei Ono, Kōen no tanjō (Tokyo: Yoshikawakōbunkan, 2003), pp.131-32.

Many art galleries and museums were constructed in Ueno Park after the Tokyo National Museum was built. Thus, what was once a grand temple complex with numerous halls, stupas, and sub-temples, which symbolized the prestige of the Tokugawa shogunate, has today been completely transformed into a public park serving as a mainstay of culture and the arts, with a large cluster of cultural facilities.

3.

The 1851 Universal Exposition in Hyde Park was a chance not only to showcase Britain’s national might, but also to spread the English-style public parks to all four corners of the globe. In fact, there was an American who had been to see the UK’s various types of public park a year earlier. His name was Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903). Of particular interest to him was Birkenhead Park in the up-and-coming town of Birkenhead, across the river from Liverpool. Birkenhead Park was the first park to be created by a local government using public money; designed by the aforementioned Joseph Paxton, it opened in 1847. The 400,000 ㎡ area on the periphery of the park, which covers an area of around 510,000 ㎡, is a residential district; revenue from the sale of that land for housing was used to fund the development of the park. Olmsted was not only astonished by the sophistication of the technology used in developing Birkenhead Park, but also impressed by the sight of so many people freely enjoying the beautiful grounds, irrespective of wealth or class. He decided that the United States, as a democratic nation, should also have a “People’s Garden” like this. *7

*7. Frederick Law Olmsted, Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England, ed. Charles C. McLaughlin (1852: rpt. Cambridge: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003), p.91.

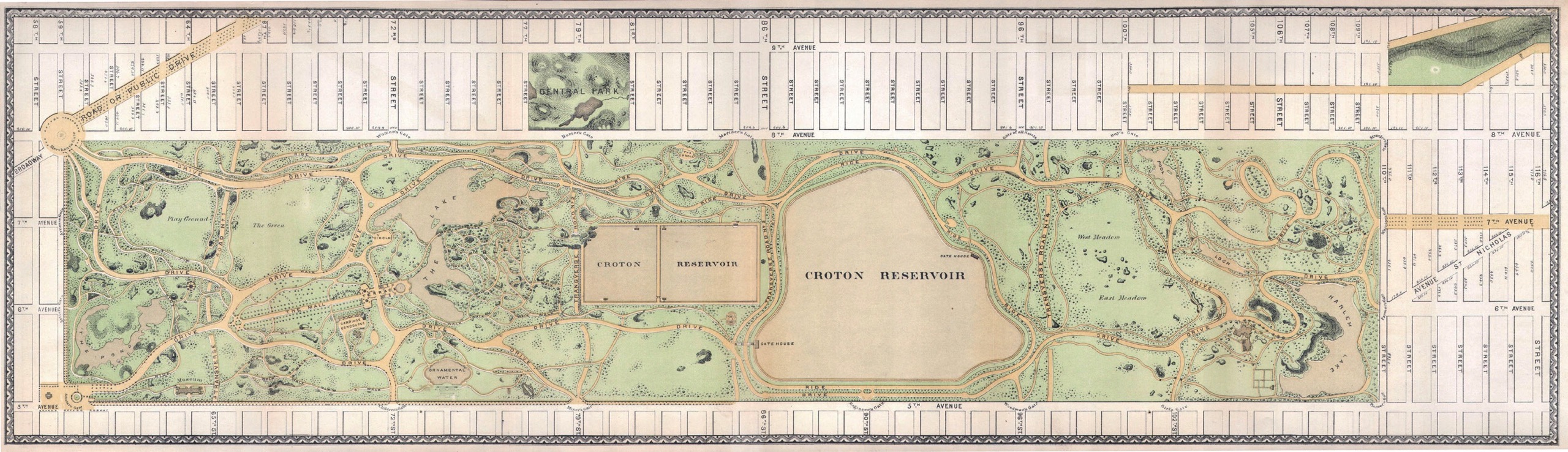

Olmsted eventually went on to design the USA’s first public park: Central Park, in the Manhattan area of New York. The march of urban development and population growth were driving the desire to create a park in New York at that time. The architect Calvert Vaux (1824-94) invited Olmsted to enter the competition to design Central Park with him and their “Greensward Plan” was adopted in 1858. It would be 1873 by the time the plan was completed and Central Park officially opened; what had initially been a poorly drained wasteland with exposed bedrock in places, which was dotted with the huts of low income earners, was transformed into an entirely bucolic landscape that made the most of its natural topographic features. Thus, its designers succeeded in creating an immense urban park covering a rectangular area of around 4 km from north to south and about 0.8 km from east to west, right in the middle of Manhattan Island’s grid-like network of streets. (Fig. 8) It really is just like a “synthetic Arcadian Carpet, grafted onto the Grid,” as Rem Koolhaas described it. *8 Various groundbreaking experiments were trialed in the park, including separate circulation systems for crosstown traffic, horse-drawn carriages, horseback riders, and pedestrians.

Fig. 8. Central Park (1869)

*8. Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York: a retrospective manifesto for Manhattan (New York: Monacelli Press, 1994), p.22.

As a model of a city park, Central Park’s influence was felt not only within other parts of the USA, but also worldwide. The role that Olmsted fulfilled in the construction process did not fit neatly into such conventional categories as gardener or architect, so he called the field “landscape architecture” and referred to himself as the first landscape architect. Olmsted was involved with a huge number of park design projects in the USA thereafter, as well as contributing to the establishment of “park systems” ─ a way of linking multiple parks in a single city ─ and the founding of Yosemite and other national parks.

Although Central Park was not used as the venue for an exposition, *9 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, one of the world’s largest art museums, is located on the park’s central eastern edge. It originally opened in a building at 681 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan in 1872, becoming the USA’s first international art museum, but moved into a purpose-built museum designed by Calvert Vaux at its current location in 1880. It subsequently underwent frequent structural alterations and extensions to house its growing collection, which now runs to more than three million items, making it the USA’s largest art museum. Plans to build cultural facilities in Central Park were repeatedly formulated thereafter, but no construction other than that required for the Metropolitan Museum of Art was permitted. Nevertheless, many cultural facilities, such as the Guggenheim Museum mentioned below, are located facing the park.

*9. However, Olmsted designed the layout of the World’s Colombian Exposition in 1893, which was held in Chicago’s Jackson Park.

4.

As described above, the five public parks established in accordance with a Great Council of State Decree in the 1870s had all previously been part of the grounds of a temple or shrine, or a notable beauty spot. In other words, this means that they had been park-like spaces prior to the founding of the public park system. In particular, during the rule of Tokugawa Yoshimune in the first half of the 18th century, cherry trees were planted at Asukayama and a number of other locations around the city of Edo, creating numerous beauty spots that the common people could access freely to enjoy viewing the trees when in blossom.

However, the lineage of park-like spaces can be traced back even further. For example, places called “Ichi no Niwa,” or market gardens, formed in marginal areas, including riverbanks, sandbars, beaches, moors, and hills. One could describe them as Japan’s most ancient open spaces, which not only served as a place for a variety of people to exchange goods, but also played host to a diverse array of activities, including performing arts, games, rain-making rituals, fortune-telling, and executions.

Interestingly, stones frequently played an important role in these places. These stones not only served as markers identifying the place, but were also believed to be tutelary deities blocking the entry of evil spirits, guardian deities of the city and its marketplace, which ensured that business would prosper, or phallic deities promoting the prosperity of people’s descendants.

At the same time, while Japanese gardens evolved into a variety of styles throughout the ages, their common feature was a composition of natural stones that served as the skeletal structure of the garden. Even Sakuteiki (Records of Garden Making), which is Japan’s oldest extant book on gardening and is believed to have been compiled in the latter half of the 11th century, documents that the fundamental part of gardening is “erecting the stones.”

Although Japan’s public parks, which were established at a time of extreme Westernization during the Meiji period, developed out of temple and shrine precincts and gardens, they were modeled on Western parks, so it is questionable whether they are actually grounded in Japan even today. Since ancient times, there must have been park-like spaces other than those that we know today as public parks. In exploring these, we can find clues in not only the stones of “closed gardens” such as private gardens, but also the stones of “open gardens” such as the aforementioned Ichi no Niwa.

To put it in somewhat simplified terms, the gardens and parks of the Western model are formed by enclosing a space, as the etymology of these words suggests. However, in the case of Japan, erecting stones comes before enclosure, so gardens are formed around stones with a perpendicular quality. Similarly, park-like places grow up around stones that survive in a variety of locations in urban spaces.

For example, temple and shrine precincts are often park-like places because they were believed to have a sanctuary-like character as a refuge due to the deities enshrined there. Today, the statues and buildings at temples and shrines are objects of veneration, but if we look at the reasons why they were originally erected there, we can see that they often had their origins in a specific natural object of some kind. The most important of these were natural stones that became objects of faith called Iwakura/Iwasaka, which were believed to be dwelling places in which deities were enshrined. Accordingly, we can say that the park-like places that sprang up there originate from stones.

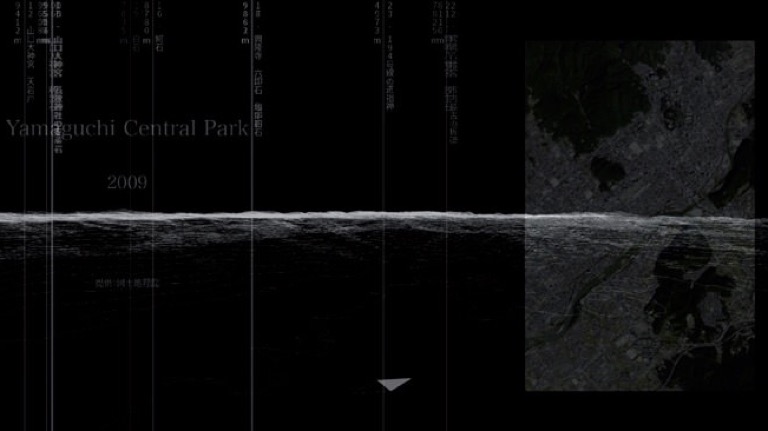

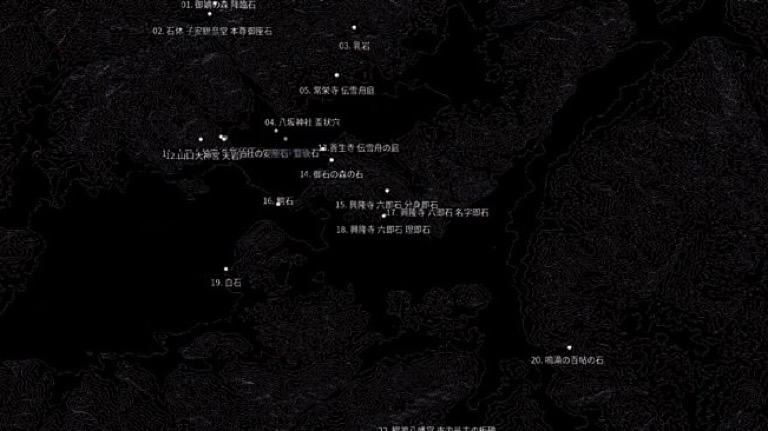

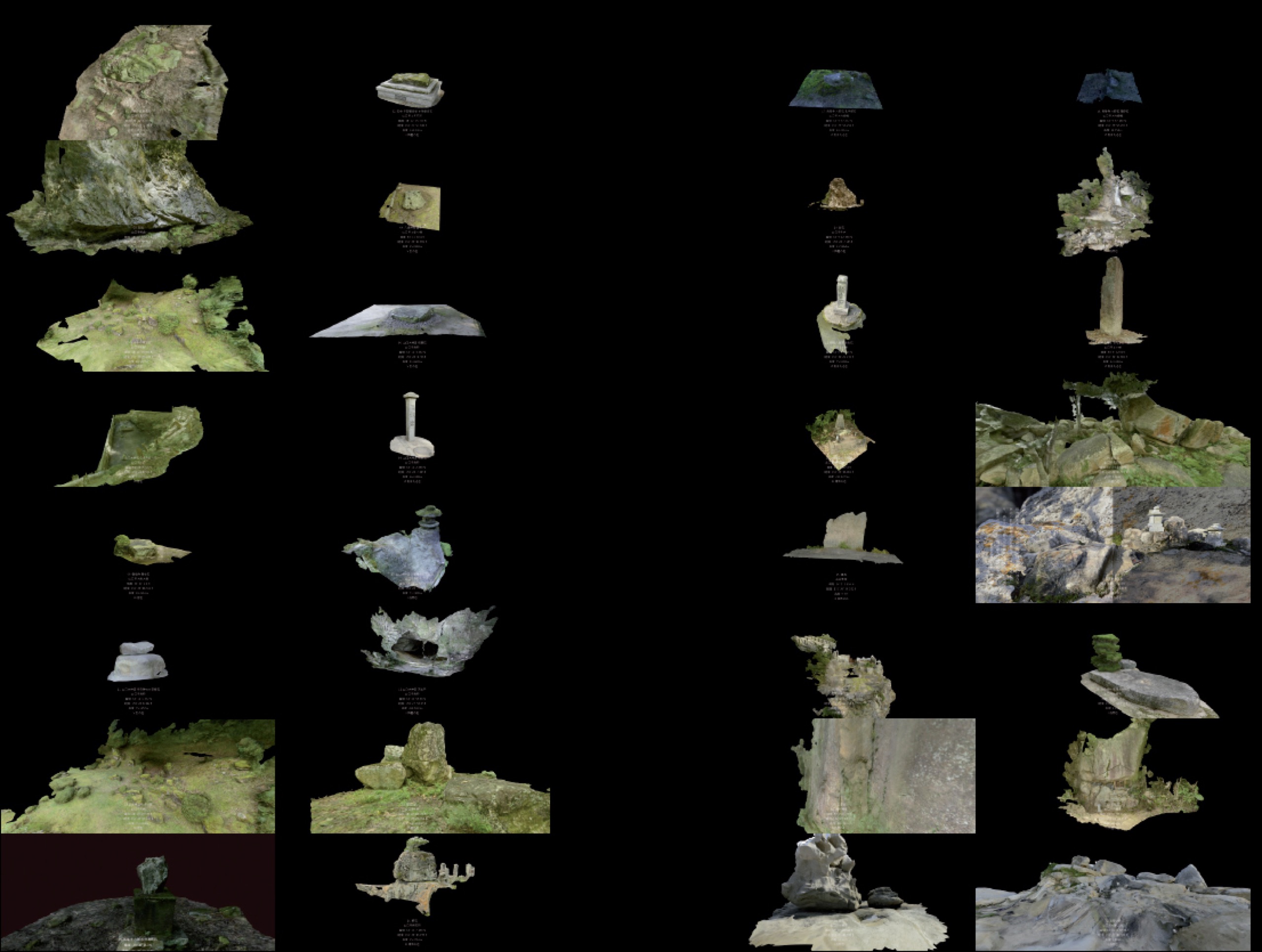

Using stones as clues in this way opens up a whole new angle on the lineage of Japan’s wealth of park-like spaces. For the PPP, we carried out fieldwork focused on stones in the city of Yamaguchi, where YCAM is located. The first output from this work was “St 1.0 ─ From «Niwa» Stone to Park,” *10 which was presented at Promise Park Project [Research Showcase] (2014). In 2015, we developed this work further and ultimately highlighted stones at 32 locations in Yamaguchi City in Park Atlas. (Fig. 9) A detailed discussion of the stones at these 32 locations can be found in “Archive of Stones in Yamaguchi City.” In the course of our research, we came to believe that stones in Japan can be classified into the following six categories. Stones that exist in their natural state among countless others (I. Natural Stones) and those among them that frequently became objects of worship as the dwellings in which deities were enshrined, because their strong sense of consistency could be construed as giving them a certain permanency (II. Theophany Stones). Stones remain consistent in shape and position over time, so they are also used as distinguishing marks to indicate boundaries (III. Boundary Stones). Sometimes, several natural stones are combined because of their aesthetic appeal; as described above, throughout the history of Japanese gardens, this has been the act of laying the foundations of a Japanese garden (IV. Garden Stones). Stones with a shape resembling male or female genitalia are often believed to bring fertility or prosperity (V. Stones of Life). Most of these stones are basically used unprocessed, but some stones are inscribed to provide written information or visual representations (VI. Inscribed Stones). Of course, not all stones are easily classified and a single stone may fulfill multiple functions, in many cases. This multilayered nature is another attribute of stones and is the reason why it is possible to repurpose stones, such as the Rokusoku stones referred to at the beginning.

*10. For details, see "A Park Established over Ruins".

Fig. 9. Archive of Stones in Yamaguchi City.

Humans, other animals and plants live and die; buildings decay and are rebuilt; urban environments change. Amid this process, stones survive unaltered because of their powerful sense of permanence. Each stone that survives in each key place in a city retains an accumulated memory unique to that location, making them the most primitive form of archive media. One could therefore describe them as the key to temporal and spatial communality. Accordingly, tracing back the history of these stones enables us to uncover the oldest layers of the city and also throws into relief the overall shape of collective parks woven by the network of park-like spaces ─ a constellation of stones, if you will. (Fig. 10)

Fig. 10.

1. Ochaku Forest, Kōrin-seki / 2. Sekitai Koyasu Kannondō, Honzon Goza-seki / 3. Chichi-iwa / 4. Yasaka Shrine, Haijōketsu / 5. Jōeiji Temple, the Garden attributed to Sesshū / 6. Yamaguchi Daijingū Shrine, Momioki-ishi / 7. Yamaguchi Daijingū Shrine, the Garden attributed to Sesshū 8. Yamaguchi Daijingū Shrine, Sekikantō / 9. Ryūfukuji Temple, Bungo-ishi / 10. Yamaguchi Daijingū Shrine, Sagi-iwa of Yasaka Shrine / 11. Yamaguchi Daijingū Shrine, Anzan-seki of Taga Shrine / 12. Yamaguchi Daijingū Shrine, Ama no iwato / 13. Zenshōji Temple, the Garden attributed to Sesshū / 14. Stone in Goishi Forest / 15. Kōryūji Temple, Rokusoku-seki, Bunshinsoku-seki / 16. Wani-ishi / 17. Kōryūji Temple, Rokusoku-seki, Myōjisoku-seki 18. Kōryūji Temple, Rokusoku-seki, Risoku-seki 19. Shira-ishi / 20. Hyakujō-iwa at Narutaki Waterfall / 21. Waninaki Hachimangū Shrine, Hōjō-seki / 22. Waninaki Hachimangū Shrine, the oldest Stone Stupa in the city 23. Dōsojin God on Route 194 / 24. Kōgō-iwa / 25. Tate-ishi / 26. Hi no yama / 27. Takuhi Shrine / 28. Akasaki Shrine, Shiomachi-ishi of Yoshitsune / 29. Sanjō-iwa / 30. Gyōja sama / 31. Saru-iwa / 32. Iwaya no hana

5.

The three parks showcased by Park Atlas as the origins of modern public parks are Hyde Park, Central Park, and Ueno Park. Of course, parks have developed not only in the UK, USA, and Japan, but also across the globe in a variety of ways and there are countless parks with distinctive features worthy of attention. In Park Atlas, we highlighted three examples of new parks: the Mundaneum project, Parc André Citroën, and Yamaguchi City Central Park.

The PPP started by focusing on the collective intelligence held by parks. As already stated, parks have been readily used as venues for expositions; moreover, as well as temporary events such as these, parks have also frequently functioned as a matrix for the coexistence of multiple cultural facilities, including art galleries and museums. Parks were not just spaces where natural objects ─ namely animals and plants ─ from around the world were gathered in one place, but also places where even man-made objects from all four corners of the globe were exhibited; these were places that should have been called “archive spaces of the world.” The key thing is that these were open spaces that anyone could enter.

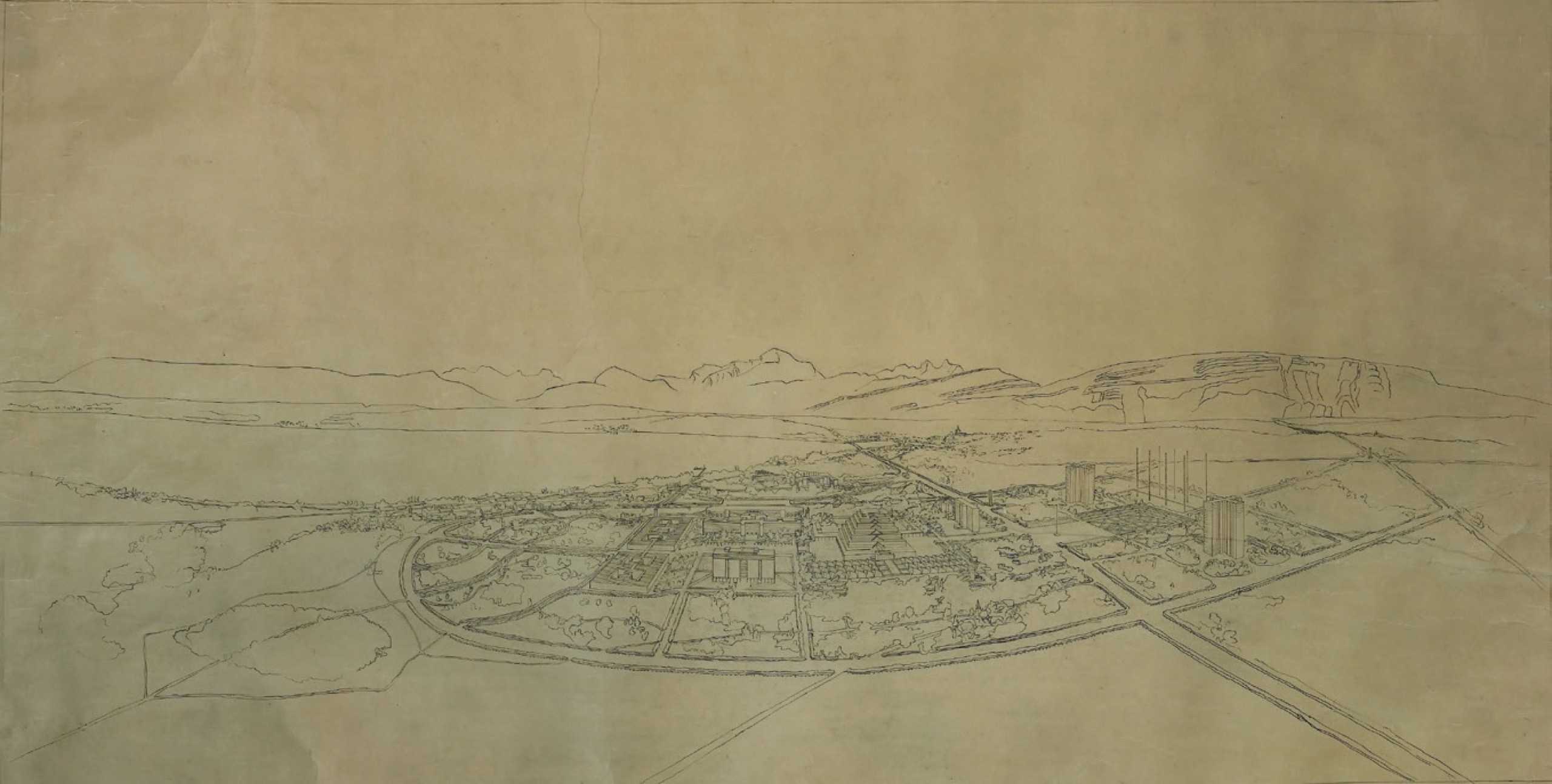

Pursuing this aspect of parks to the utmost extreme was the Mundaneum project. Over the course of the 1910s and 1920s, the Belgian Paul Otlet (1868-1944), who is renowned for his contribution to the establishment of the League of Nations and has been described as the father of the Internet, envisioned the Mundaneum, a central repository for the world’s knowledge. In 1925, he commissioned the architect Le Corbusier (1887-1965) to design it.

Seeking a method of gathering and sorting books from around the world, Otlet and Henri La Fontaine (1854-1943) had devised the Universal Decimal Classification (which is still used today) in 1905. Otlet also advocated “documentation,” which was the term he used for collecting not merely books, but all information, such as that contained in newspapers and photographic images. At the Brussels International 1910 exposition, he and La Fontaine jointly presented a plan for an organization to carry out this task, and they went on to establish the Palais Mondial (World Palace) in 1920, in the Parc du Cinquantenaire in Brussels. This later became known as the Mundaneum, a neologism coined from “mundus,” the Latin word meaning “world.” Otlet developed this idea further, devising a plan for a Mundaneum in the form of a city. Initially, he thought of founding this in Brussels, but eventually switched the location to Geneva, where the League of Nations was based, and asked Le Corbusier to design it.

In Le Corbusier’s plan, the Mundaneum was to be an extension of Ariana Park, where the United Nations is now sited, and was to incorporate not only a world museum, a library and a university, but also a stadium and infrastructure such as a road and a railway. This was a utopian vision of a park city. (Fig. 11) Particularly worthy of attention is the pyramid-shaped World Museum. Each floor of the World Museum was to deal with a different era and was designed so that visitors would take the elevator to the top floor and then descend the square spiral corridor in a clockwise direction, viewing exhibits on a circuit that would take them on a journey through humanity’s progress in each historical period worldwide as the exhibition corridors gradually widen outward. *11

Fig. 11. Le Corbusier, Mundaneum. ©FLC/ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2017, E2502

*11. This structure is also thought to have been linked to the configuration of the venues for the Universal Expositions. The venue for the International Exposition of 1867, which was held at the Champ de Mars, a public open space in Paris, consisted of multiple concentric ellipses; by making a circuit of each ellipsis, visitors were able to view all of the exhibits in the same category from different countries, while moving in a straight line radiating out from the center enabled them to view all of the exhibits from a particular country. This configuration was maintained at the Second National Industrial Exhibition (1881) in Ueno Park, among others. One might say that the structure of the World Museum was almost a three-dimensional spiral version of this. As is frequently pointed out, this structure, in which visitors first take the elevator to the top floor and then descend in a spiral, is also similar to the Guggenheim Museum (1959) designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, which adjoins the southeastern side of Central Park. Hajime Yatsuka, Ru Korubyuje: Seiseiji toshiteno yurubanisumu (Tokyo: Seidosha, 2014), pp.129-61, for example, also provides a detailed description of the positioning of the World Museum’s structure.

This Mundaneum project ultimately never came to fruition, but the structure of the World Museum repeatedly featured in Le Corbusier’s plans thereafter as a “Museum of Unlimited Growth.” One example of this is the National Museum of Western Art, which opened in Ueno Park in 1959. *12

*12. Other examples of museums of unlimited growth include an art museum in Ahmedabad (designed in 1951) and a museum and art gallery in Chandigarh (designed in 1958), both in India.

On the other hand, Parc André Citroën is a park with an area of around 140,000 m2, which was developed in 1993 on the site of the former Citroën motor company plant on the banks of the river Seine, in Paris. The overall composition and the southwestern half were designed by landscape architect Alain Provost (1938-), while the northeastern half was designed by gardener and thinker Gilles Clément (1943-) and architect Patrick Berger (1947-). The latter half contains seven gardens laid out in linear fashion from northwest to southeast: the Garden in Movement, the Blue Garden, the Green Garden, the Orange Garden, the Red Garden, the Silver Garden, and the Golden Garden. Of these, it is the Garden in Movement, which appears at first glance to be just a wild, untended patch of land, that actually embodies Clément’s advanced concept of a garden. (Fig. 12)

Fig. 12. Garden in Movement

Usually, if a garden’s form changes with the passage of time, maintenance is carried out to restore it to its original shape. However, in Clément’s Garden in Movement, the natural movement resulting from the growth and change of plants is respected; the role of the gardener is to select which of these multiple movements to keep and which to reject. The Garden in Movement in the Parc André Citroën began with the sowing of seeds on a patch of waste ground in 1991. Clément observed and recorded the changes that the plants went through; in addition, birds and the wind introduced plants that were not among the seeds initially sown, so today it is home to a complex array of flora.

The Garden in Movement is a microcosm of jumbled flora on a global scale; Clément himself sees the garden as a “planetary index,” which also “anticipates the configuration of the flora in tomorrow’s landscape.” *13 Moreover, visitors themselves are involved in the movement in this garden, stepping on the plants as they pass through; consequently, all visitors to this garden have the potential to be gardeners.

*13. Gille Clément, Le Jardin en mouvement: de la vallée au champ via le parc André-Citroën et le jardin planétaire (Paris: Sens et Tonka, 2007), p.186.

Thus, the Parc André Citroën’s Garden in Movement emexhibbodies the forefront of modern garden ideas, presenting new ways of handling nature in public parks and pointing up the relationship between nature and humans. French gardens were traditionally formal gardens, like those at the Palace of Versailles. Nevertheless, radical ideas ─ which one could even describe as oriental ─ that overturn this concept of gardening have become established within the very same country.

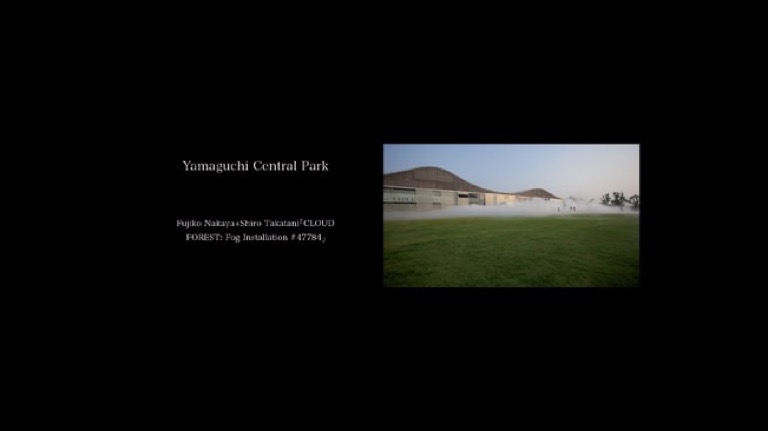

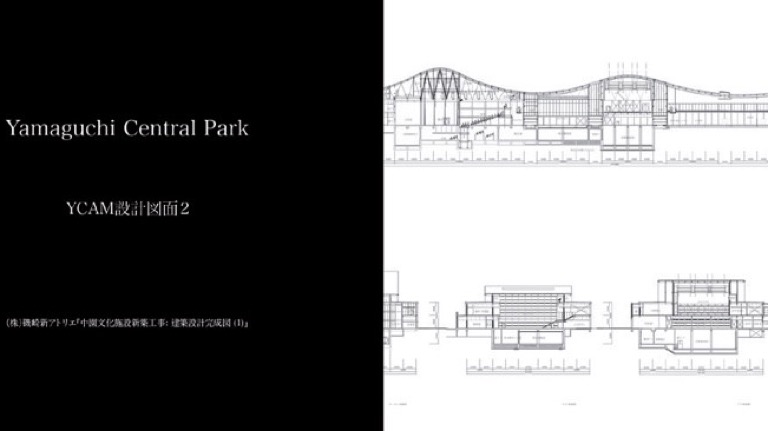

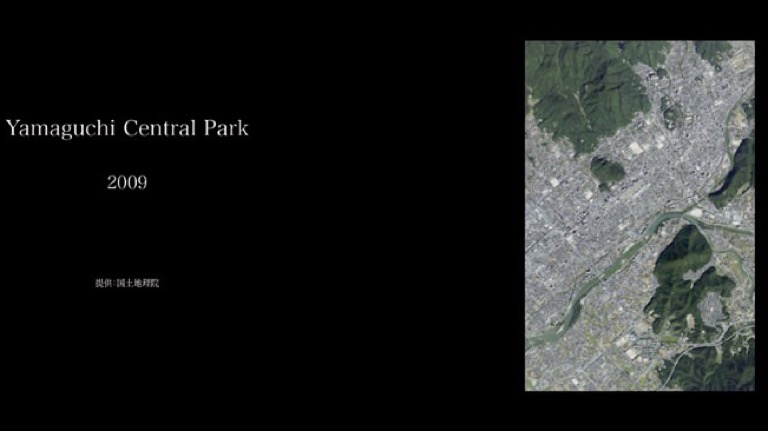

The third park, Yamaguchi City Central Park, is the park in which YCAM is sited. A detailed description of the park is beyond the scope of this chapter. YCAM is a complex consisting of exhibition spaces, a theater, a cinema, and a library, which was, along with Yamaguchi City Central Park, designed by the architect Arata Isozaki (1931-). Since its opening in 2003, YCAM has invited artists and researchers from across the globe to work with YCAM InterLab, its inhouse research and development team, to produce works of media art and engage in a variety of other activities. The park’s lawns are always full of people, but they are also an exhibition space; works exhibited there to date include “CLOUD FOREST” (2010) by Fujiko Nakaya + Shiro Takatani (Fig. 13) and the “Korogaru Pavilion” (2013).

Fig. 13. “CLOUD FOREST” (2010) by Fujiko Nakaya + Shiro Takatani

6.

The number six seems to have been frequently used as a figure signifying a massive system. This is particularly the case in the Eastern world.

For example, there were Rikkei (六経, the Six Classics of Confucianism): the Odes, the Documents, the Changes, the Spring and Autumn Annals, the Rites, and the Music. Rikugi (六義, Six Forms) are the forms of writing in the Odes, namely folk song, festal song, hymn, narrative, explicit comparison, and implicit comparison. Adhering to this classification, the Kokin Wakashū categorizes the six forms of waka poetry as allegorical, enumerative, metaphorical, allusive, plain, and congratulatory. In addition, kanji characters are classified into Rikusho (六書, Six Methods) by composition and use: pictograms, simple ideograms, compound ideographs, phono-semantic compound characters, derivative cognates, and rebus (phonetic loan) characters. In Buddhism, as well as the Rokusoku, there are Rokudō (六道, the Six Realms of Karmic Rebirth): hell, hungry ghost, animal, demi-god, human, and gods. There are also Rokusō (六窓, Six Windows), Rokujō (六情, Six Emotions), and Rokkai (六界, Six Worlds ), the six internal sense organs ─ eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind ─ and Rokkyō (六 境, Six Borders) or Rokujin (六塵, Six Dusts), the six external sense objects — material objects, sound, odor, taste, touch, and conceptual objects. Then there are Roppō (六方, the six directions) (north, south, east, west, up, and down) and Rokurin Ichiro Setsu (六輪一露説, The Theory of Six Circles, One Dewdrop), a principle of Noh. The examples are endless and too numerous to list in full here.

Park Atlas is composed of two parts: case studies of parks on the so-called Western model and ancient Japanese park-like spaces. The former focuses on six parks, showcasing Hyde Park, Central Park, and Ueno Park as examples of modern public parks, and the Mundaneum project, Parc André Citroën, and Yamaguchi City Central Park as examples of new parks. The latter is an archive of stones at 32 locations in Yamaguchi City, classified into six categories. These two parts contrast the Western model with the Eastern, or Japanese model; the modern with the premodern; the macroscopic perspective with the microscopic perspective; and inclusive spaces with divergent spaces.

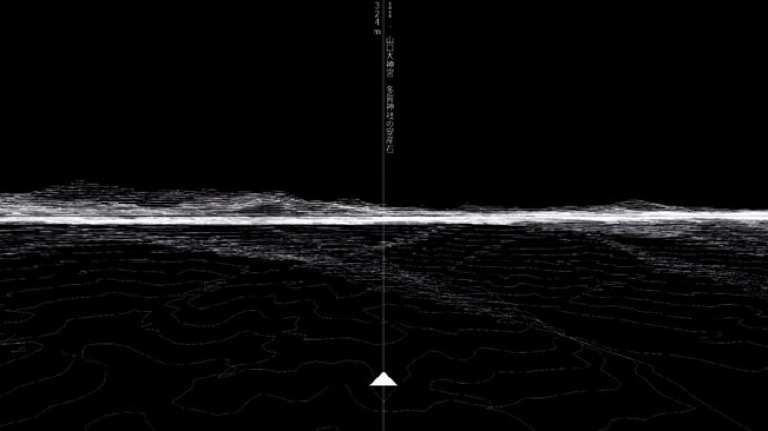

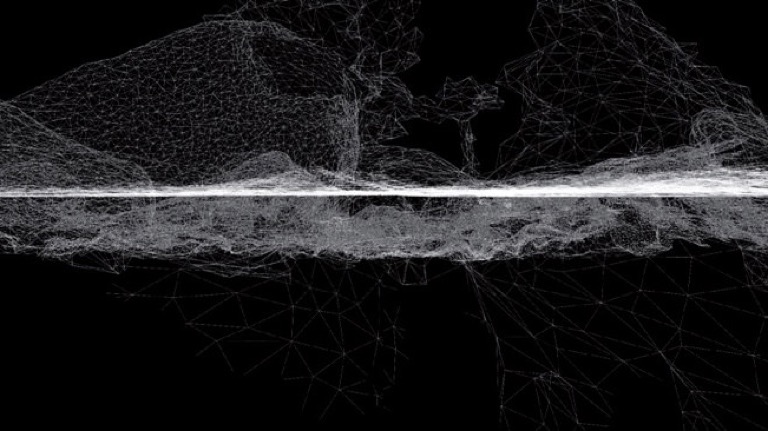

We have adopted the format of an atlas (i.e. a collection of maps or visual archive) to serve as a system for visualizing and exhibiting these archives. A screen measuring 1,800 mm high by 12,800 mm wide was hung in YCAM’s second-floor gallery, in front of the window facing out toward the mountains to the northwest. Four projectors projected landscape-oriented images onto the screen, which was basically divided into six areas, effectively creating “six windows.” (Fig. 14)

Fig. 14.

The first half presents around 1,000 drawings, maps, photographs, and paintings of the six parks, as well as providing a chronology and bibliography. Initially, the development of Hyde Park, Central Park, and Ueno Park is traced separately, in parallel, but eventually the images of the three parks become intertwined. Each image is tagged on the basis of its format and content; for example, in a scene in which the tags “bridge” and “statue” have been selected, images from the three parks are displayed across the top of the screen. This enables the visitor to understand the similarities and disparities between the three different parks, rather than simply looking back over the development of each park. The rules for each scene are predetermined, but the combination of images in each scene and their layout is not fixed, differing each time. As images of the three parks become entangled with each other, images of the Mundaneum project, Yamaguchi City Central Park, and Parc André Citroën also enter the mix, marking the transition to the part about new parks. The jumble of scenes then progressively unravels and images of the three new parks appear side by side. (Fig. 15 – 17).

The last scene in the first half is an aerial photograph of the area around YCAM, which transitions into the latter half’s archive of stones in Yamaguchi City. (Fig. 18 – 25) This part presents a computer-generated 3D topographic representation of Yamaguchi City, 3D CGI representations of stones at 32 locations in Yamaguchi City and high-resolution images of the texture of the stones, and text from relevant old documents. The images on the screen change from perspectives providing an overview of Yamaguchi City from the air to a close-up of a spot where one of the stones is located, before showing 3D and high-resolution images of the stone, including its texture, as well as text from historical sources. The perspective then returns to an aerial view before flying to the location of another stone. This virtual tour of the stones using 3D computer images sometimes unfolds on three screens simultaneously and sometimes on just a single screen; sometimes the next stone is chosen at random, but sometimes it is the next one in sequence in the same group, based on the aforementioned set of six steps. Earlier, I stated that stones alone remain constant as animals, plants, and cities undergo change. This system enables the viewer to gain a palpable sense both of the relationships between the stones in each location and the surrounding topography that has survived the centuries, as visualized through abstract information in the form of contour lines and 3D data, and of the texture of the stones as an interface with which people have come into contact over the generations.

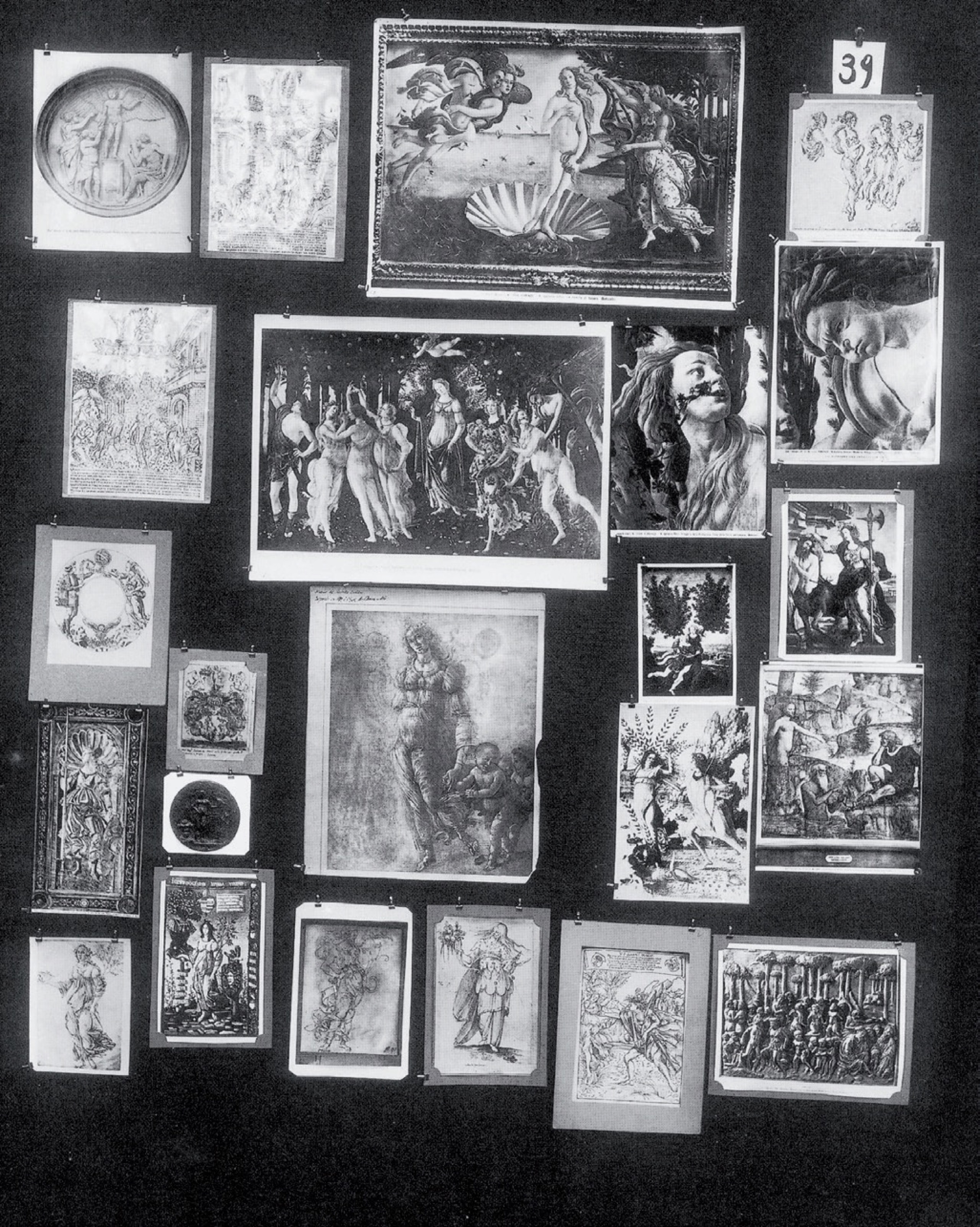

One atlas technique that we found a useful point of reference was “Mnemosyne Atlas,” an unfinished work by the German art historian Aby Warburg (1866-1929). (Fig. 26) In his twilight years in the late 1920s, he pinned onto a black canvas a variety of images, from pictures of ancient sarcophagi to photographs from contemporary news reports and constantly rearranged their layout while attempting to analyze the immense and labyrinthine history of visual images. Those photographs of the 63 panels remain today, with 971 images in total, but Warburg’s commentary on them has not survived. *14

Fig. 26. Mnemosyne Atlas, Panel 39.

*14. Interestingly, the time that Warburg was compiling Mnemosyne Atlas overlapped with the period when Otlet was working on the Mundaneum project and “atlas” was an important concept in Otlet’s ideas as well. For example, see Raphaèle Cornille et autres, Le Mundaneum: Les archives de la Connaissance (Bruxelles: Les Impressions nouvelles, 2008), pp. 47-49.

The intentions behind Mnemosyne Atlas were many and varied, but among others, it was an attempt to understand the schizophrenic nature of the Western world ─ the nymph in a state of ecstasy (mania) and the grief-stricken river god (depression); the vita activa and the vita contemplativa ─ from an immense bundle of images. *15 One should note that Warburg himself suffered from a psychiatric disorder and was hospitalized for several years before producing the Atlas. After returning to his work, he sought not only to assemble his thoughts in a linear way in writing, but also to use an atlas to juxtapose images on canvas, to serve as a nonlinear embodiment of his thoughts. The positional relationships between the collection of assorted images laid out on the canvases were not fixed at all and Warburg is said to have rearranged them constantly.

*15. According to the entry in Warburg’s diary for April 3, 1929 (Aby Warburg, Tagebuch der Kulturwissenschaftlichen Bibliothek Warburg mit Einträgen von Gertrud Bing und Fritz Saxl, hrsg. von Karen Michels und Charlotte Schoell-Glass [Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2001], p.429).

With this nature, Mnemosyne Atlas would seem to resemble the miniature gardens used in play therapy, a technique used in psychology. One might call it an “upright miniature garden of created images,” through which Warburg sought to analyze the schizophrenic nature of the Western history of images, as well as attempting to maintain his own mental stability. Jun Tanaka likens Warburg’s constant rearranging of the images on the canvases to the behavior of someone continually dealing cards to tell their own fortune, stating, “This act was an exploration of the past, tunneling down through the strata of European memory stretching back over thousands of years; sometimes... it was even a prophecy of the future, potentially a premonition of doom.” *16

*16. Jun Tanaka, “Kaidai Vāruburuku no tenkyū he (AD SPHAERAM WARBURGIANAM): “Munemoshune Atorasu” no tasōteki bunseki,” in Munemoshune Atorasu (Tokyo: Arina shobō, 2012), p.671.

As described above, the section of Park Atlas featuring the six parks presents around 1,000 images in combinations and configurations that vary each time, while the section that constitutes an archive of stones takes a tour of 32 locations where stones can be found. The former really is just like shuffling and rearranging an enormous pack of cards to tell one’s own fortune, while the latter is like a game of sugoroku (双六; a Japanese board game), in which one continually rolls the dice and moves the counters, in a closed circuit that has no goal. Thanks to these two game-like systems, Park Atlas evokes two conflicting things ─ modern parks following the Western model and the lineage of park-like spaces in premodern Japan ─ discovering similarities and disparities between them and seeking to identify lessons for the parks of the future.

This might also be an act of exploring through parks the optical unconscious or the mediated unconscious on which Kazunao Abe focuses. *17 As Georges Didi-Huberman says, Mnemosyne Atlas could not have been created without photographs. *18 Photography became established at the same time as modern parks. Focusing on the relationship between parks and photography in his discussion of Central Park, the artist Robert Smithson wrote, “The notion of the park as a static entity is questioned by the camera’s eye.” *19 Although Park Atlas is an atlas of parks, parks can also, as described hitherto, be regarded as archive spaces of the world, so one could describe them as atlas spaces in physical form. Therefore, Park Atlas is an atlas of atlases. Moreover, I stated above that Mnemosyne Atlas was a “upright miniature garden of created images.” Park Atlas is also a miniature garden of images of parks as an atlas, while the archive of stones in Yamaguchi City is a miniature collective park woven by a constellation of stones, rendered in 3D computer imagery. In conclusion, Park Atlas itself is a small park in its own right.

*17. See pp.186-187 of this book.

*18. Gerges Didi-Huberman, L’image survivante: Histoire de l’art et temps des fantômes selon Aby Warburg (Paris: Minuit, 2002), pp.452-56.

*19. Robert Smithson, “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Dialectical Landscape” in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, eds by Jack Flam (California: University of California Press, 1996), p.160.

It is a form of telling one’s own fortune by shuffling the images, and a game of sugoroku on a closed circuit with no goal. It is a miniature atlas of parks, which continually envisages parks as archive spaces of the world by means of these two game-like systems. That is Park Atlas.

Postscript: I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Mr. Ryosuke

Kondo for his invaluable assistance in the writing of this text.