That is what I mean when I refer to the necessity for ruins: ruins provide the incentive for restoration, and for a return to origins. There has to be (in our new concept of history) an interim of death or rejection before there can be renewal and reform. Old order has to die before there can be a born-again landscape. (…) Many of us knew the joy and excitement not so much of creating the new as of redeeming what has been neglected.

─ J.B. Jackson, The Necessity for Ruins

In many cases, people believe an urban park equals Central Park. This park in New York City, which dates back to the 19th century, has become an archetype for parks worldwide and was originally aimed to be a green refuge where people could rest peacefully even amid the hustle and bustle of city life. The park was established in a picturesque style, full of green romance, and one that attempted to become an island refuge that is distinguished from the outside of the park, including high walls to protect against the city’s daily life and culture. In the 20th century, most urban parks, regardless of region or country, have made dichotomous relationships with the city while wearing a Central Park “uniform,” which is to say the city is seen as evil and the park is seen as good. There was no exception with modern parks in Seoul that were influenced by the West and Japan during the Korean Empire and Japanese colonial eras.

In the 20th century, romantic landscapes in parks similar to Central Park were transplanted to many Korean cities, one of which was Seoul. With many park projects led by the government, old-fashioned parks were reproduced with wide lawn carpets, areas with ample foliage and shade, pavilions built in exactly the same style, and playgrounds for kids. However, not a few parks degenerated into a nuisance for people in cities. Parks always suffered from the pressure of urban development. Even a little negligence in management led a park to become a hotbed of crime or a haven for the homeless. Parks were becoming places of contradiction that took up large spaces in a city yet which everyone was hesitant to visit. Changes in the concepts of speed and movement brought by automobiles, the brilliant development of the tourism industry, the development of suburban homes with better environments than parks, and the popularity of multi-functional shopping malls that were far more attractive than parks all questioned the necessity of parks.

The situation drastically changed after the turn of the 21st century. Only then did parks become popular once again. Indeed, parks emerged as a medium for urban regeneration and even a political product in Seoul, which shows proof of this change in mentality. If we consider it a natural phenomenon that originated from people’s nostalgia about an eco-friendly life, that would be too narrow a viewpoint. Modern cities, which have been transformed in an unpredictable direction over a cycle of change, came to require a major operation called “regeneration,” and a strategy to create parks in this spirit is now being carried out. However, a park that is re-connecting to 21st-century metropolises is not an isolated refuge like Central Park. A park is a main character in a city. It is like a blood vessel that moves through the city and takes the initiative in the transformation and evolution of the city while continuously conversing with the city. Sites such as brownfield sites, polluted land, post-industrial sites, landfills, and relocation sites for military camps ─ the types of sites which were not found in cities in the past ─ are now being turned into parks. We don’t even need to take examples of foreign parks such as the Duisburg- Nord Landscape Park (a ruined factory complex that turned to a park for urban regeneration), New York’s Fresh Kills Park (which is turning from a vast pile of waste to an environmental park), Volks Park Potsdam and Downsview Park in Toronto (both examples of military bases turned into parks). Seonyu Water Purification Plant itself became a park filled with sublimity and synesthesia. The Nanjido waste mountain became a park full of landscapes that arouses the senses. The American military base at Yongsan will become a national park. Well-known parks in Seoul from the 21st century such as Seoul Forest, Cheonggyecheon, West Seoul Lake Park, and Gyeongui Line Forest Park are all examples of post-industrial ruins turned into parks. One more, Seonyudo Park, is a leading example of a post-industrial ruin revitalized into a park.

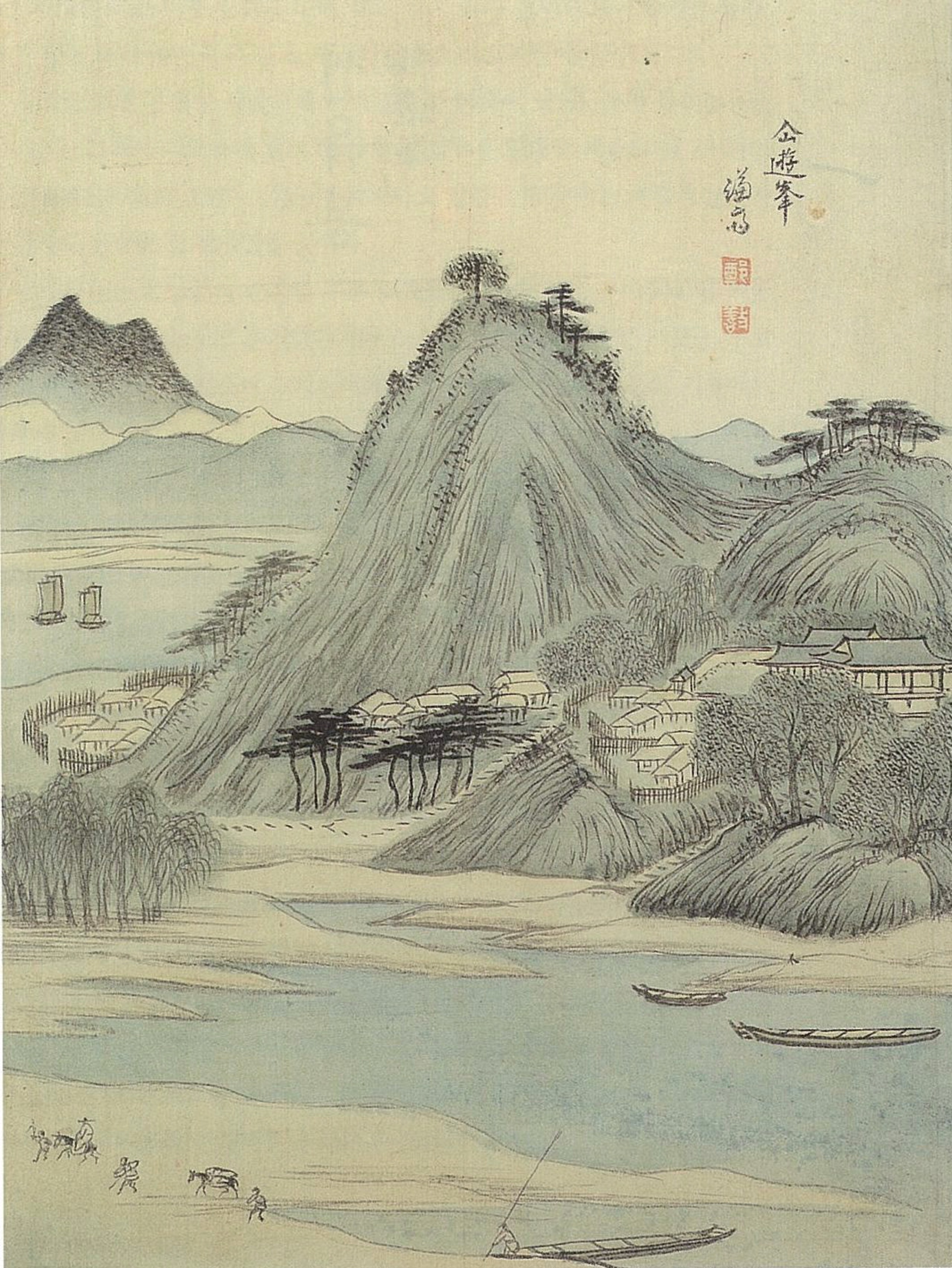

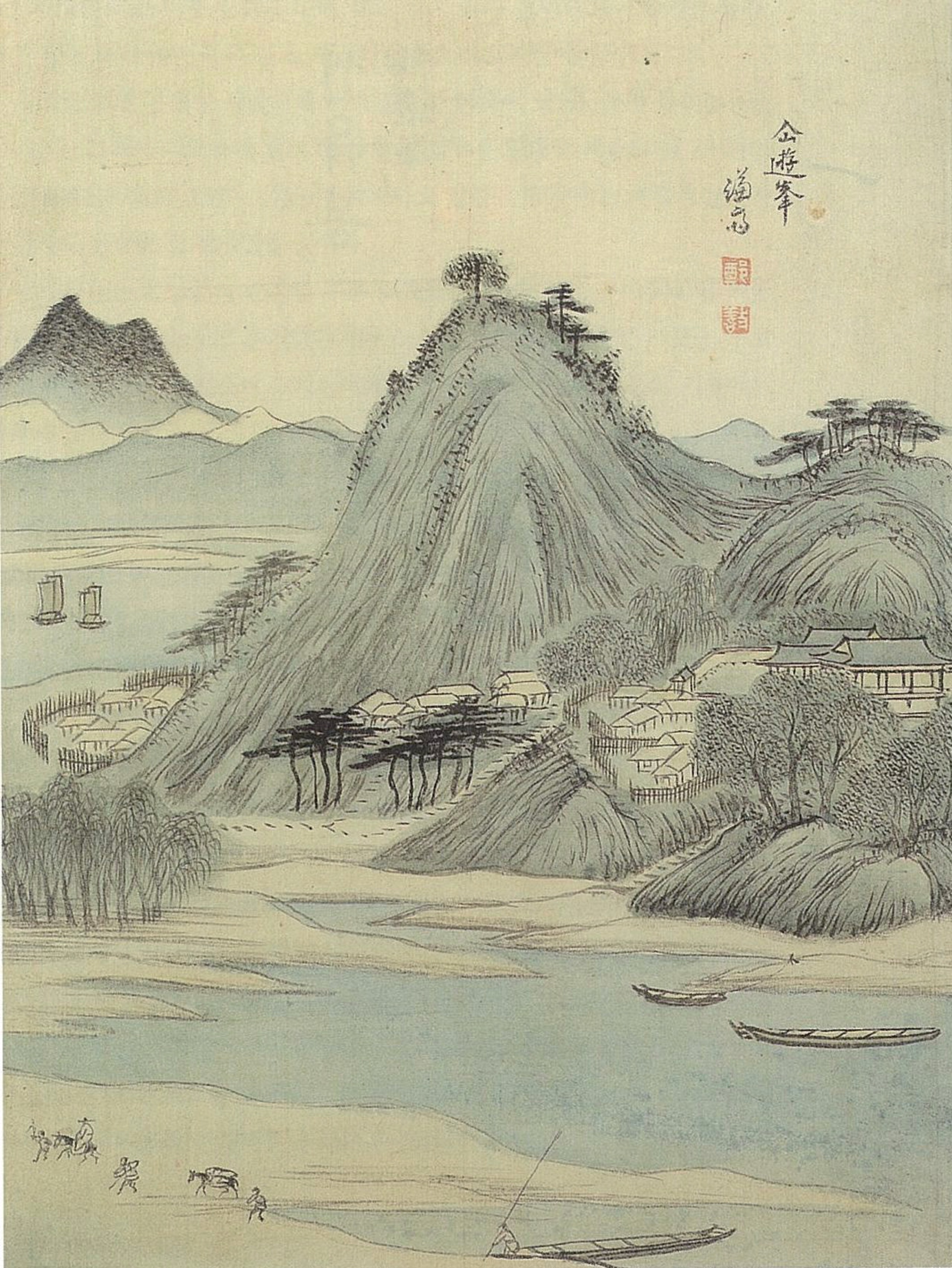

Seonyudo was not an island but a 40-meter-high peak that, while not very large, was elegant. Being slightly covered by water from the Hangang River, Seonyu Peak was literally a peak where Taoist hermits used to take strolls. Seonyu Peak was the best of the magnificent views on the west side of the Hangang River that connected Yanghwanaru with Chamdubong (today’s Jeoldusan Mountain). It was also one of the eight great views of the Hangang River. This was a place that housed many pavilions and was one of Seoul’s most picturesque sites. In order to enjoy the scenery around Seonyu Peak, literary people in the Joseon era gladly climbed this area or walked around it. In addition, Chinese envoys left many poems celebrating the Hangang River and surrounding landscapes when they visited the peak.

Among Gyeomjae Jeong Seon’s works, Gyeonggyo-myeongseungcheop (“Album of Scenic Spots of Seoul and Vicinity”), which captured views of the Hangang River and the areas around Inwang Mountain, also features spectacular views of Seonyu Peak. Of the 33 paintings, almost 20 are themed around the Hangang River, with three of them showing Seonyu Peak: Yanghwa Hwando (“Summoning the Yanghwa Ferry”), Geumseongpyeongsa (“Marsh Covered with Sand in Geumseong”), and Soakhuweol (“Waiting for the Moon to Rise at Soakru House”). The three landscape paintings clearly show the smoothly rising peak with a pavilion on it directed towards Mangwonjeong and Yanghwajeong pavilions as well as the leisurely excitement of sailboats coming and going.

As many Koreans know, there was no concept of a park in the Joseon Dynasty. However, there was a culture of enjoying outdoor leisure time for both the aristocracy and ordinary people in Joseon. H. B. Hulbert, who lived in Korea from 1886 to 1892 and opened a school, observed “Koreans have no idea of parks as decorated public spaces or places for recreation. However, they enjoy strolling through verdure, where they can appreciate the beauty of nature.” Before the Western culture of parks was introduced to Korea, Koreans had a unique culture of leisure in a way of enjoying views and sceneries while climbing nearby forests or mountains. Although places with magnificent views like Seonyu Peak were different from Western parks, they played a similar role to the parks we use today; they were interpreted as special places that were more than simple parks, which were unlike today’s parks.

The great flood of Seoul in 1925, which was an unprecedented natural disaster in the history of the city, had an enormous influence on the geography of the city and the history of the Hangang River. Water reached the front of Namdaemun and the center of Seoul was filled with water. Later, banks were built on both sides of the Hangang River and rocks were gathered from Seonyu Peak for this purpose. That is when deconstruction began on Seonyu Peak. The banks essentially separated people from the river, and a veritable hill was formed along the river.

In the 1940s, sand and pebbles were gathered from Seonyu Peak in order to build an airfield on Yeouido. That is when the beautiful peak disappeared and it turned into what basically became a flatland. The late architect Guyon Chung commented on this by saying, “Seonyu Peak was flattened to fill the bottom of Yeouido and came to have the shape of an island floating like a lengthy ship, but was ultimately deserted on the Hangang River like a piece of useless land.”

The construction of the 2nd Hangang River Bridge (now Yanghwa Bridge) in 1962 and the Hangang River Development Project in 1968 finally changed Seonyu Peak into an island. While river flowed between Seonyu Peak and the end of the Hangang River, Seonyu Peak became a flat island in the middle of the river and surrounded by concrete retaining walls six to nine meters high. The rapid urbanization of Seoul changed the fate of Seonyudo Island ─ a mountain-turned-island ─ once again in 1978 when a water purification plant was completed there and started to supply water around Yeongdeungpo, where a number of factories were located. Like a power plant, a water purification plant is thoroughly off limits to the general public. Together with the Danginni Thermal Power Plant, Seonyudo’s water purification plant was a leading industrial facility established along the Hangang River. Seonyudo Island became a forbidden land for citizens and was completely forgotten by us all. It silently carried water to Seoul residents during the modernization and industrialization of the city, with its presence eventually forgotten by people. No one was interested in it, and only a limited number of people could visit it. Most of us could not see the island even though it continued to exist right in front of our eyes.

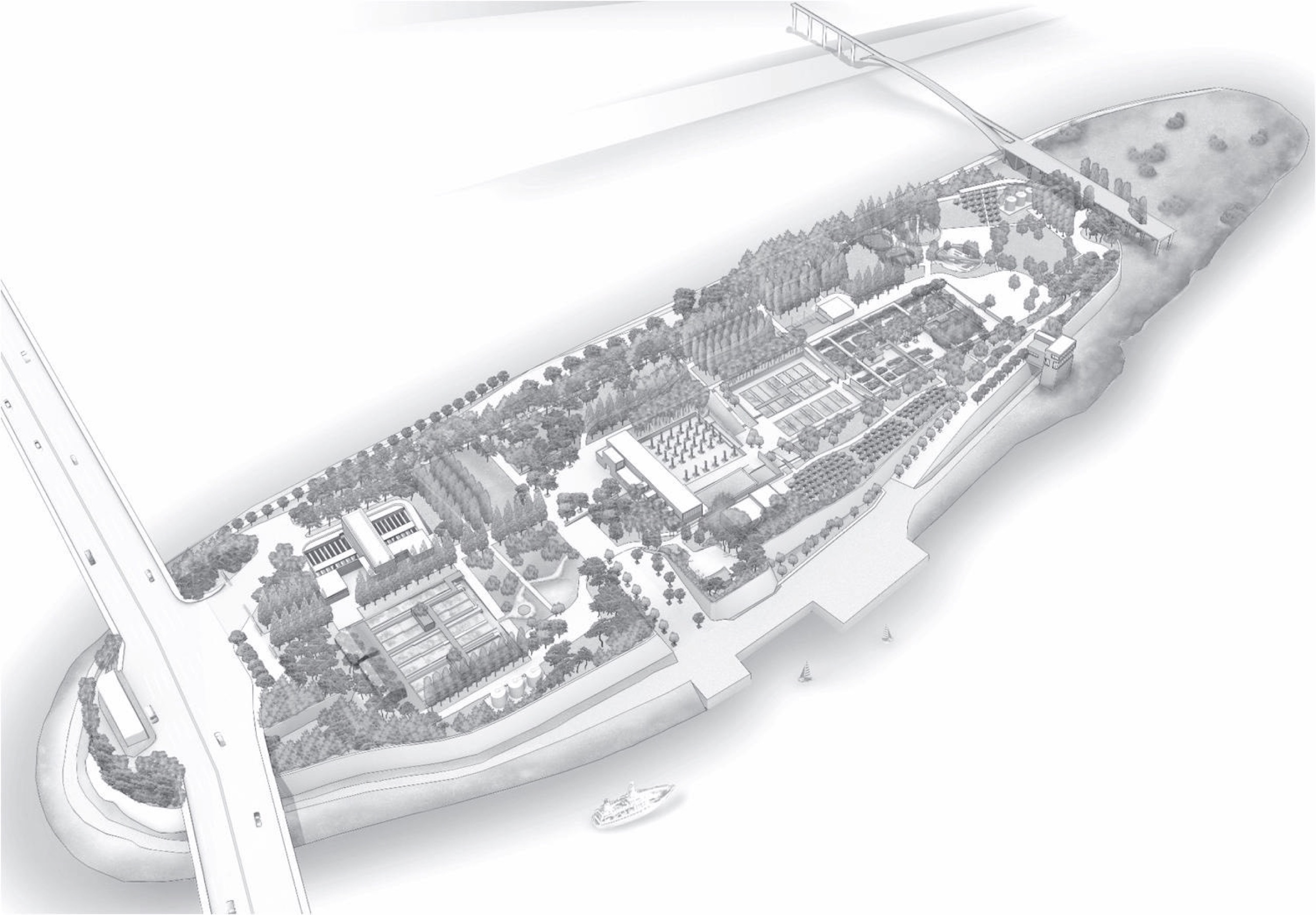

Later, the Gangbuk Water Purification Plant was established in Guri, and the water supply system across Seoul changed, so the Seonyu Water Purification Plant was not necessary any more. Then, in 1999, the function of the Seonyu Water Purification Plant was integrated into the Noryangjin Water Purification Plant, meaning Seonyudo Island lost its function as a water plant. The Seoul Metropolitan Government decided to make Seonyudo Island ─ which covers more than 10,900 square meters ─ a park as part of the “New Seoul, Our Hangang River” project. In December 1999, it selected a design plan through a competition. After a year and a half of construction, Seonyudo Park was opened in April 2002, right before the 2002 FIFA World Cup. In addition, by making the pedestrian bridge that connects Hangang River Park and Seonyudo Island, the forgotten land of Seonyudo Island returned to the forefront of people’s lives.

Seonyudo Park is considered a masterpiece that opened a new horizon for parks that recycled industrial legacies by leaving the site and structure of industrial facilities in place and reusing the same systems and processes. At Seonyudo Park, the landscape designer did not pursue traditional design to fill an empty space with new objects. At the same time, he did not intend to represent natural landscapes or idealized images of nature. Designing a park through the discovery and reorganization of the existing objects can be compared to contemporary art using common objects in everyday life as subjects for art. Seonyudo Island is an objet trouvé that is the essence of Seonyudo Park’s design. Discovery was made in two dimensions. One was the concept to change a ruined site into a park; the other was a means of spatial design to use existing objects. With its useless water purification plant, Seonyudo was terrain vague. In a post-industrial society, terrain vague is actually a land of new possibilities. It is a space that, while uncertain and unproductive, ultimately lends it more freedom. This gives an area like this the potential to be transformed into a place of memory, one in which people can experience the traces of time.

The strategy of discovery appears more concrete in spatial design. Designing Seonyudo Park started with discovering the traces of a seemingly useless place. Later, new usages and meaning were brought about by morphing or reusing these traces. Archeological design is all about rediscovering and preserving what is seemingly useless. A crucial factor in this design was selecting some of the water purification plant’s traces and transforming it into a place where people could remember the past. In other words, to make time a part of this space rather than simply designing a space was an issue with this design. Interest in temporality is also a topic of the latest environmental art. Temporality also appears in various patterns such as change, movement, variability, and uncertainty. If modernism yearned for eternity and tried to express it, postmodernism actively accepts variability. Nature or materials that change over time are not an obstacle in design, but are used and celebrated as unique characteristics.

Seonyudo Park has facilities that were built by renovating the existing facilities, including a visitor center, the Hangang River History Museum, a cafeteria, a water purification basin that reused the underground site of the water purification plant, the Garden of Green Pillars, the Aquatic Botanical Garden, the Garden of Time, and a playground and theater that recycled the plant’s circular structure. Essentially, all the existing facilities were reused or removed before new elements were added. The underground space, building columns, and walls were retained, while existing buildings were renovated. Plants were added and pedestrian paths were formed to better experience the park. Instead of creating powerful images, the materiality of raw materials was emphasized. Changing the focus from visual images towards materiality means those who experience the park are involved in the structural logic of design rather than being indulged in forms.

On top of the logical standards often used to evaluate Seonyudo Park, such as being labelled an “alternative experiment in resolving the crisis of traditional urban parks,” “a recycling strategy for post-industrial sites,” and “respect for time and memory beyond form-focused design,” we need to focus on the “sensory” characteristics unique to this park. With a wooden deck attached to the Seonyugyo Bridge, the lonely wind from the river that blows towards the deck feels extremely light; the sights and smells of Seoul are experienced all at once through the Hangang River; the mesmerizing montage of naked concrete, cold metal, and life of plants can be felt; long paths of contemplation that require solemn steps of introspection rather than stressful physical movement are actually “aesthetic.” This is because aesthetic judgement is not logical but instead sensory. Seonyudo Park, a veritable “Palace of Senses,” replaces traditional landscaping aesthetics that are usually represented by the beautiful and the picturesque with the “sublime”. In short, the materiality of ruins creates the aesthetics of the sublime. The power of materiality that governs Seonyudo Park originated from the fragments of time, whether broken concrete, rough cement columns, or rusty and corroded steel pipes. However, what connects these fragments is an aesthetic aura of the sublime.

In the aesthetic experience at Seonyudo Park, there is a certain path that is totally different from meditation on concepts like harmony or beauty. It does not appear as spatial perception and logos-like detachment, but as the eruption of a temporal flow and pathos. It is more of a chaos than cosmos, more of Dionysus than Apollon. At Seonyudo Park, we do not experience clear objects with the characteristics of order and harmony, but instead a certain feeling that disorderly, formless, and uncertain objects evoke.

We do not feel disharmony in a landscape where a city’s fiercely rising skyscrapers and thickly growing reeds are paralleled. We live in a time when a ruin ─ once seen as a nuisance ─ can be turned into a great park. There are those who believe the traces of ruined industrial facilities can become meaningful landscapes. People experience a different sense of aesthetics even in concrete blocks and rusty steel structures left behind from a removed plant. Today, park aesthetics are moving from beauty and the picturesque to the sublime. The aesthetic of the sublime revealed in Seonyudo Park is the sign of a phenomenon whereby the dualistic concepts of city/park and culture/ nature from the 20th century collapses and a new point of reconciliation is established. In contemporary parks, the sublime is rediscovered as an aesthetic strategy in practice beyond the concept of theoretical aesthetics. Traditional landscape aesthetics, which has pursued green make-up skills focusing on the imitation and representation of natural beauty, is going through a process of deconstruction. The territory between parks and aesthetics is now waiting to be reestablished.