Following the death of Emperor Meiji, who swiftly promoted the modernization and Westernization of Japan, Meiji Shrine was built to enshrine his spirit and commemorate his achievements. The shrine complex consists of two parts: the Naien (inner precinct) and the Gaien (outer precinct). In early August 1912, very soon after the emperor’s death on July 30 that year, the industrialist Eiichi Shibusawa and others put forward the Memorandum on the Construction of the Meiji Shrine, in which they proposed a plan that became the kernel of today’s Meiji Shrine. The Naien eventually opened in 1920 and the Gaien in 1926.

The construction of Meiji Shrine triggered substantial progress in modern Japanese landscape architecture. The shrine poses numerous potential questions, including challenging us to find in its completion some significance for the completion of Tokyo’s establishment as the nation’s capital.*1 What this section focuses on is the unique configuration of the “park” realized through its dualistic structure, consisting of the Naien and Gaien.

*1: Sohō Tokutomi, “Meiji Jingū,” in Meiji Tennō seitoku hōshō kōenshū, ed. Kokumin shinbunsha (Tokyo: Min’yūsha, 1921), p.6.

The land that became the inner precinct of Meiji Shrine had been occupied by the Ii clan, the lords of Hikone Domain, since the Edo period. However, following the demise of the Tokugawa shogunate, the land was confiscated by the new government and eventually became the Yoyogi Goryōchi, an estate owned by the Imperial family. This, then, is the place where a shrine was built to enshrine the spirit of Emperor Meiji. The surrounding man-made forest, which covers an area of 700,000 ㎡, was planted on what had, until then, been a barren wasteland. (Fig. 1)

In the initial plan, the forest was to be a coniferous one, with Japanese cedars, Japanese cypress, and Japanese red pines, similar to the forests at such major shrines as the Ise Grand Shrine and Kasuga Grand Shrine. However, as the land was sited in a warm-temperate forest zone and would be exposed to smoke pollution from nearby areas, the plan was judged to be unfeasible. Accordingly, landscape architecture scholar and forestry experts Seiroku Honda, Takanori Hongō, and Keiji Uehara devised the “Meiji Shrine Inner Precinct Forest Plan,” a plan to create an “eternal forest” by planting a climax forest consisting mainly of evergreen broad-leaved trees such as evergreen oak, chinquapin, and camphor trees, which would develop over the course of 100 years. As Yoshiko Imaizumi states, a German forestry aesthetic was introduced there, rooted in Goethean conviction that “nature is always right,” but at the same time, the completely primeval forest rediscovered by Uehara around Emperor Nintoku’s burial mound also served as a key point of reference.*2

*2: Yoshiko Imaizumi, Meiji Jingū: ‘Dentō’ wo tsukutta dai purojekuto (Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 2013), p.158.

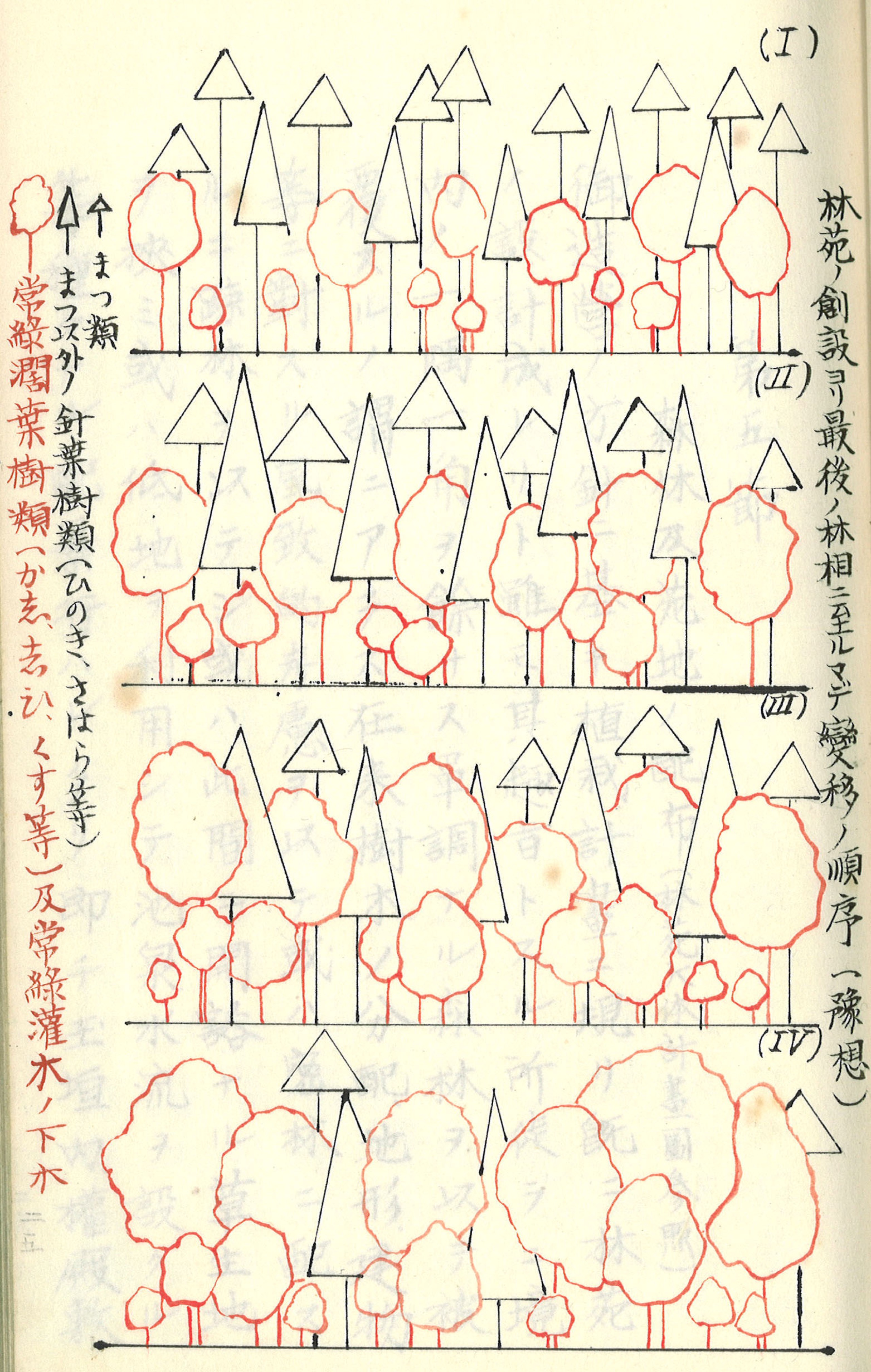

To establish the shrine forest, almost 100,000 trees were donated, not only from across Japan, but also from Manchuria, Taiwan, and Korea. The plan by Honda and his colleagues involved forming an upper canopy consisting of red and black pines, among others, as well as planting such trees as evergreen oak, chinquapin, and camphor trees, aiming to reach forest succession with these latter species as the main constituents in the final stage (Fig. 2). The Naien will celebrate the centenary of its dedication in 2020; today, the shrine where the spirit of Emperor Meiji resides is surrounded by a full climax forest consisting of evergreen oak and chinquapin, covering an area about 15 times that of the main shrine building. It is basically an invisible realm that cannot be entered, but a recent study revealed that the forest is home to many endangered species and rare creatures.*3 Thus, thanks to Meiji Shrine, a huge sanctuary has formed at the heart of the metropolis.

*3: Chinza hyakunen kinen dainiji Meiji Jingū keidai sōgō chōsa hōkokusho, ed. Chinza hyakunen kinen dainiji Meiji Jingū keidai sōgō chōsa iinkai (Tokyo: Meiji Jingū shamusho, 2013).

The Gaien, meanwhile, was created from plots of land that were owned by people from a variety of classes during the Edo period. In 1887, it became the Aoyama Parade Ground, a military facility, and it was there that Emperor Meiji’s funeral took place on September 13, 1912. The Gaien has a western-style geometric garden structure and a vista stretching along the Ginkgo Avenue from the entrance to the Meiji Memorial Picture Gallery, which forms the heart of the outer precinct. On display in the two wings of the picture gallery are 40 Japanese-style and 40 western-style paintings depicting the life and times of Emperor Meiji and Empress Shōken. The gallery itself is inspired by the War Salon at the Palace of Versailles and the Rubens Hall at the Louvre Museum. The paintings, which were painted to a standard size of 3 m long by 2.7 m wide, were commissioned especially for the gallery, each from a different painter.

Around the picture gallery can be found a variety of sports facilities, including an athletics field and a baseball ground. As such, whereas the Naien is basically a Shinto shrine, the Gaien is a multifaceted space that is park-like in nature. Shinobu Orikuchi provided a stimulating insight when he stated that the Gaien’s picture gallery and diverse sports facilities are analogous to the emadō (shrine building where votive picture tablets are hung) and the baba (horse track for mounted archery) found in the precincts of traditional shrines, and that one could therefore consider the Gaien to be a venue for contemporary performing arts (geinō).*4

*4: Shinobu Orikuchi, “Shinshintō no kengen,” in Orikuchi Shinobu Zenshū 3 (Tokyo: Chūōkōron shinsha, 2001), pp. 392-93.

Thus, we have the Naien, a shrine surrounded by an extensive climax forest, and the Gaien, a venue for contemporary performing arts that also has Emperor Meiji’s memory at its heart. This pair of precincts addresses a number of dichotomies: Japanese style and western style; ancient style and Meiji style; tradition and innovation; and government-funded construction and donation-funded construction. They are linked by a shrine approach path (sandō) that was once called the “Urasandō” (literally, “the rear approach path”). (Fig. 3) Today, the “Omotesandō” (literally, “the front approach path”) street in Aoyama, which is lined with luxury brand boutiques, is renowned as the approach road to the Naien, but the road that links the rear of the Gaien with the northeastern part of the Naien (what is now Metropolitan Route 414) is none other than the Urasandō. The original plan was to make this road the Omotesandō, but this would have meant that the entrance to the Naien would have faced northeast (“kimon”, or “Demon Gate”), which was traditionally considered an unlucky direction that would allow evil spirits to enter. Consequently, the layout we see today was adopted.

Interestingly, before the plan to build a shrine there, the land that became the Naien, Gaien, and the Urasandō was due to serve as the venue for the Great Japan Exposition. This was intended to be Japan’s first Universal Exposition and was initially planned for 1912, but it was then postponed, with the intention of holding it to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Emperor Meiji’s coronation. The state of public finances led to the plan’s abandonment in March 1912 and Emperor Meiji died later that year, so the land ended up being used for Meiji Shrine. Accordingly, in the words of Teruomi Yamaguchi, one could say that Meiji Shrine is “the exposition transformed.”*5

*5: Teruomi Yamaguchi, Meiji Jingū no shutsugen (Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan, 2005), p. 91.

The Naien and Gaien are not linked by the Omotesandō,*6 but the Urasandō does connect them directly to each other. What meaning can be found in the fact that the Naien and Gaien are linked at the rear by the Urasandō?

*6: Although the original plan was that the Omotesandō should connect the Naien and Gaien (Yoshiko Imaizumi, Meiji Jingū, p. 192).

This dualistic structure of Naien and Gaien is reminiscent of the Inner Shrine (Naikū) and Outer Shrine (Gekū) of Ise Grand Shrine, or the inner grounds and outer grounds of the Imperial Palace. Shinobu Orikuchi described the Gaien as a venue for contemporary performing arts. In this case, I would like to discuss the “ushirodo” (back door and a space behind the back door of the Hondō (main hall of temples), a privileged topos established in the Middle Ages where sarugaku (the predecessor to Noh and Kyogen) was performed to protect the enshrined deity or temple Buddha at the rear of the building.*7 Regarding Ise Grand Shrine, Shin’ichi Nakazawa states that the Outer Shrine, which enshrines Toyouke-Ōmikami, the goddess of food and the performing arts, equates to the ushirodo for the Inner Shrine, which enshrines Amaterasu-Ōmikami, the Emperor’s ancestor.*8 This schema would also appear to be applicable to Meiji Shrine.

*7: Yukio Hattori, “Ushirodo no kami,” Shukujin ron: Nihon geinōmin shinkō no kenkū (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 2009), pp. 1-25.

*8: Shinichi Nakazawa, “Tetsugaku no Ushirodo,” in Mikurokosumosu I: Yoru no chie (Tokyo: Chūōkōron shinsha, 2014), pp. 185-87 and pp. 209-12.

The ushirodo was also the place where foreign deities were enshrined. At the rear of the Meiji Shrine’s Naien is a vast English-landscape-garden-style lawn extending in front of the Hōmotsuden (Treasure Museum). It would be fair to say that this is one of the most beautiful parts of Meiji Shrine. (Fig.4) As stated above, the Naien is basically a Japanese-style, traditional shrine space consisting of climax forest. This part alone presents the appearance of a western-style garden, almost as though an extraneous element from the Gaien had sneaked into the rear of the Naien via the Urasandō. However, at the same time, one might also say that the power of the various arts in the Gaien supports the space of the Naien from the rear via the Urasandō. This, then, would seem to be where the necessity of linking the Naien and Gaien from the rear lies ─ is it really a coincidence that the National Noh Theatre stands exactly halfway along the Urasandō? Conversely, the climax forest in the Naien imbues the contemporary performing arts that take place in the Gaien with the basis of their dynamism via that same Urasandō, does it not?

Meiji Shrine thus has a unique dualistic structure that formalizes the relationship between nature and the activities of humankind; this would seem to offer clues that might point the way when thinking about the parks of the future.

There is one more interesting thing to mention. The dualistic structure of Meiji Shrine is actually very similar to the structure of the exhibits at the 2015 PP Exhibition. From the outset, Ms. MOON was thinking in terms of producing a pair of new installations to be placed in two contrasting rooms. As a result, the two installations were brought to fruition in the form of a carpet of Nishijin fabric and a carpet of moving images. The former, which was laid out in the light, airy foyer, had a park-like quality, with children running around or sprawled out on it every day; in effect, it served as the Gaien. On the other hand, the latter, in Studio B, was a space in which one could become lost in meditation in the darkness ─ almost as though surrounded by an invisible forest ─ with no scope for play, in contrast to the foyer. This shrine-like ambience thus made it the Naien.

The line of visitor flow linking these two installations more or less corresponds to that around the Naien and Gaien at Meiji Shrine. At Meiji Shrine, you can enter the Gaien through the main gate to the south, go all the way through to the rear of the park, turn left, proceed along the Urasandō, and then enter the Naien from the rear. Similarly, at the PP Exhibition, visitors entered through the front entrance to YCAM, walked over the carpet in the foyer all the way to the back, went up the stairs, and then turned left at the second-floor gallery to enter the room of moving images in Studio B. Thus, the second-floor gallery corresponds to the Urasandō. The vestigial approach path in the Great Japan Exposition was used to display Park Atlas. Put simply, the structure of the PP Exhibition was unexpectedly Meiji-Shrine-like.

However, at the same time, it also leveraged YCAM’s spatial attributes. This might well be thanks to PP’s synchronicity with the ideas of Arata Isozaki, who designed YCAM ─ “Future cities are themselves ruins” is one of his most famous quotes. What we must also not forget is that the three stages ─ carpet, atlas, and video ─ also correspond to the three repurposed Rokusoku-seki stones.

This, then, is the form in which the PPP was translated into reality. One wonders what its next incarnation will look like.