In the Promise Park Project (PPP), we selected a number of cities across the globe and researched approaches to modern parks in the context of the circumstances of each city and the history of its formation. (This work might well continue in the future.) The cities that we chose were London, home to Hyde Park, the birthplace of modern parks; New York, whose Central Park was inspired by Hyde Park; and Tokyo, where the establishment of parks progressed rapidly in the wake of the Meiji Restoration, during a period of dramatic cultural change. (Furthermore, we plan to add Seoul ─ MOON Kyungwon’s hometown, where ultra-modernization is progressing apace ─ to this list in future.)

These cities are all massive economic centers that have gone through the processes of modernization (metamorphosing from modern to postmodern and beyond); we also chose to study the Japanese city of Yamaguchi, which is on a totally different level from these metropolises. Why did we include Yamaguchi? Our primary motivation was the fact that YCAM is based in Yamaguchi City (one of the factors that inspired YCAM’s establishment was Japan’s rapid transition from a society based on heavy industry to an information-based society) and we needed to drill down into local history in greater depth, but it also sprang from the fact that Yamaguchi in its present form as a city and the transitions that it is experiencing are so different from the big cities mentioned above. So what are the specific points of difference ─ one might even call it asymmetry ─ between them?

It would be fair to say that modern parks began with the securing of equal rights and the legal democratization of cities that progressed in parallel with the economic development triggered by modernization, and the resultant standardization of visual elements. However, the hidden intention of the PPP is actually to unearth through research from an anthropological perspective the things obscured by modern parks, and the layers of history as evidence; in this approach, “earth diving” (based on the “earth diver” concept posited by Shin’ichi Nakazawa) can be applied.

Yamaguchi City is the capital of Japan’s Yamaguchi Prefecture. It is a small city, with just 140,000 residents in its central district, and, unlike the neighboring cities of Ube and Shunan, heavy industry is not a key industry there. Perhaps because of this, it escaped unscathed the aerial bombing campaign that the U.S. military launched on the Japanese mainland during World War II. The Shinkansen bullet train line and the Sanyo main line cross through the city’s south-central Ogori district on their way from east to west, but because of its location between the big cities of Hiroshima, Kitakyushu, and Hakata, there has been no major commercial development around the Shinkansen station and the city retains a very flat profile, with hardly any tall buildings, even now. Thanks to this, it is an almost-unheard-of example of a place where a city built by an ancient society 1,500 years ago and the topographical profile thereof ─ what one might call the prototype of the city ─ is still visibly preserved on the surface of the modern city. Its history can be traced back to the 7th century and the rich sediment of its heritage is immediately perceptible when one looks at the city in its present form. (This sedimentary nature is a point that it has in common with such cities as Nara, Kyoto, and Barcelona, but in Yamaguchi’s case, one could say that it remains in a more primitive form.) Another reason why the city’s shape and nature remained fundamentally unaltered over the centuries was that it survived the turbulence of the Sengoku period through to the Edo period without frequent changes of feudal lord or reorganization of domains, so nobody sought to transform the city in order to stamp their presence on it. This state of affairs might very well be described as miraculous, given that the Yamaguchi area achieved such economic might in the Muromachi period that it was considered to be one of the nation’s major political strongholds. Another distinctive feature of Yamaguchi City is the convergence of topographic elements around it: to the south, there is the coast, while to the north, east, and west are low mountains and hills. A large river runs through the city from north to south, with a narrow basin on either side. Ancient Jomon remains have been discovered along the river. In ancient times, it was one of the country’s foremost areas for the production of high-quality copper, silver, and lead (and coal, in early modern times); the Suzenji district, located in the south-central part of the basin, housed a mint that produced Japan’s oldest large copper coins, helping to generate a great deal of wealth. It has also been pointed out that, as a result, east-west transport links with the central government then based in the Kinki region and technology for remote communication tailored to the local terrain (beacons and the like) were developed from an early stage.

The urban environment ruled by the Ouchi clan for 800 years is the prototype for the Yamaguchi City of today. The Ouchi clan were descendants of Prince Imseong (Rinsho Taishi), who was said to have been the third son of King Seong of Baekje, one of the kingdoms of the Korean Peninsula. Imseong came ashore on the coast of Suo, to the south of Yamaguchi, and was received by Prince Shotoku, who appointed him ruler of Suo Province, the area encompassing the place where Imseong landed in Japan. The Ouchi clan prospered until internal discord and the Mori clan brought about their downfall in the mid- 16th century. In particular, during the Muromachi period, the Ouchi held a monopoly on marine transport and western trade (with China under the Ming dynasty, as well as the Joseon and Ryukyu kingdoms), holding so much power that they served as administrators for the shogunate for a time. Most notably, in 1467, immediately after the Onin War reached Kyoto, the Ouchi invited merchants and cultural figures fleeing Kyoto to come to Yamaguchi, famously nurturing the magnificent Ouchi culture through the presence of artists such as Sesshu (the inventor of the hatsuboku, or “splashed ink,” technique) who established a uniquely Japanese style of ink wash painting. It has been pointed out that the exodus of people of culture to the western capital of Yamaguchi resulted in the flourishing of unique cultural activities that were an enriched mixture of the Kitayama and Higashiyama cultures of northern and eastern Kyoto, blended with the continental cultures of China and Korea.

From the perspective of urban design, the shape of Yamaguchi as it is today has its origins in a decision taken by the ninth lord, Ouchi Hiroyo, who achieved peace in Suo Province in 1360, during the Nanboku-cho period. Seeking to rival the central government in Kyoto, he relocated the city from the eastern bank of the river to the western bank, so that he could restructure it. He initially constructed a manmade urban environment that condensed Kyoto’s layout and replicated it in miniature; his descendants, Ouchi Yoshioki and his son, Yoshitaka, are said to have engaged in additional development later on, in the Sengoku period. What people in Yamaguchi refer to as Ouchi culture is the culture that began to flourish in this early modern Muromachi period. However, after the fall of the Ouchi clan, the loss of cultural memory and the decision by the Mori clan, who succeeded to their lands, to move their capital elsewhere, resulted in the rapid decline of Ouchi culture into obsolescence. Consequently, it is hard to detect any traces of the cultural or economic effects of Ouchi culture in Yamaguchi City today. However, rather than regarding Ouchi culture since early modern times as the origin of Yamaguchi City, which is a perspective familiar to local citizens, we decided to focus on the urban environment prior to that period of renewal. Specifically, we sought to explore the dynamic structural relationships between the city and its environment from the time of ancient societies through to the Middle Ages, as well as the relationship between the city and the movement of the sun and the cosmos, aiming for an approach that would lead us to the deeper structure of the city that modernity had lost. As described above, this is because the present shape of the city makes it ideal for examining the profile of the city in ancient times from the perspective of earth diving.

Partly because hardly any relics of that time remain, studies of the structure of the city prior to its early modern relocation by Ouchi Hiroyo have made little progress. Hikamisan, the complex that housed Kōryūji Temple and Myokensha Shrine, in the Ouchi Mihori district of Suo Province, stood on the east bank of the Kushino River and prospered for many years as the home of the Ouchi clan’s tutelary deity, but hardly any of the original shape or remains of the buildings can be seen today. Kōryūji Temple is known to have followed the “Roku-soku,” the six steps that the esoteric Tendai school of Buddhism taught were required to reach the ultimate satori, or enlightenment: “Risoku (理即),” “Myojisoku (名字即),” “Kangyosoku (観行即),” “Sojisoku (相 似即),” “Bunshinsoku (分真即),” and “Kukyosoku (究竟即).” The six steps of the Rokusoku, indicating the six stages of ascetic practice of bodhisattvas in accordance with the “perfect teaching” (engyo) of the Lotus Sutra are said to have been laid out as spatial steps running in order from south to north within the magnificent precincts of Kōryūji. In other words, the steps representing stages in ascetic practice can be interpreted as progress from the low ground of the coast, along the river, to the high ground of the mountains. Stones carved with the names of the Rokusoku are thought to have been laid out to mark the boundaries between spaces. Of the six steps, only three (Ri, Myo, and Bun) have been found so far. (There are historical sources stating that the stone markers engraved with kanji characters that served as these Rokusoku stones were laid out during the early modern period.) During fieldwork, we conducted surveys of the relationship between the stones as a distinguishing mark and their spatial representation. (These Rokusoku stones at Kōryūji Temple are just one sample. As part of the fieldwork focused on stones throughout the Yamaguchi Basin, based on historical facts in the Bocho Fudo Chushin-An (Report on the climate and culture of Yamaguchi), which is believed to have been compiled in 1842, toward the end of shogunate rule, Rurihiko Hara and the YCAM team chose a number of stones that serve as distinguishing marks and conducted a study of their positions on a ground plan of the entire Yamaguchi Basin.

Etymologically speaking, the Japanese kanji characters meaning park (公園) and its previous incarnation, garden (庭園), signify “an enclosed space,” representing both the space and the corresponding perspective on the world. In particular, “gardens” in Japan are always defined in terms of their relationship to the great sea, whether or not there is a view of the sea in the actual landscape. The presence of water in the “garden” (in the form of a pond) is more or less a portrayal of the imaginary scenery of the Utopia in the concept of the western pure land, incorporating Mount Sumeru (Shumisen 須弥山) and the great sea. In other words, rather than containing realistic elements or recreating features on the actual scale, garden-like spaces are devices that indicate the presence of a symbolic allusion, providing the viewer with a sense of space or distance far greater than the scale of the elements of which the garden is actually composed. As such, this inspires a bold hypothesis: that the structural space and enclosed precincts of Kōryūji Temple, which is thought to have been magnificent in scale, and the surrounding religious community might well have had a spatial relationship similar to that of a park, and that the spatial concept of the temples built to the north, south, east, and west might even have a proportional relationship to the Yamaguchi Basin as a whole.

Furthermore, adopting an approach based on media history, in respect of the archive functions of items other than digital media, the PPP focused on the existence of “stones” as a form of archival storage, assuming a relationship between stones as transhistorical distinguishing marks and human history. Japanese gardens always contain stones that people have deliberately chosen and placed there. These symbolize imaginary mountains, with those mountains representing remoteness from reality. At the same time, the stones are also distinguishing marks that represent the movement of the sun and the cosmos, transcending daily life. These are transhistorical deep structures that transcend individual eras in the city, and their significance is likely to have been all the more nuanced in ancient societies. (For example, there is a quite powerful theory that structures such as the stone circles of Jomon societies were used both as ritual spaces and as markers for the observation of celestial bodies.) And what if we look beyond parks and gardens to focus on all of the stones on which the layers of various eras are engraved throughout all public spaces in the city, from ancient times until the present day? Stones have a semi-permanent stability, so they are given various meanings and roles as “living archives” in each era (such as possession of physicality or a supplement to life and death) and exist in cities as cornerstones of public spaces, even as their symbolic meaning varies, affected by periodic changes in communications and economic performance. They provide clues to deciphering the long scroll of history and assist in imagining the outer boundaries/ delineation of the “enclosed space” that these diverse stones inscribe.

During the fieldwork for the PPP, we surveyed the “stones” thought to have existed in the Yamaguchi Basin since ancient times and deliberately arranged in public spaces in the city, as well as studying records thereof, and scrutinized the relationship between these and the terrain, forests, and the movement of the sun. One quite topical example of our findings was the discovery of the “Tateishi standing stone” thought to have been erected in fairly ancient times at Yotsutsuji (literally, “where four roads meet”) to the west of Suzenji. (Unlike wood, stone cannot be carbon-dated, so an accurate measurement of its age is not possible.) This large, flat piece of grantie about 2m high boasts a quite man-made singularity. It was erected beside an east-west highway that has been in existence since ancient times, leading to the site of the mint at Suzenji that produced copper coins. We discovered that the direction in which it faces corresponds exactly to the east-west passage of the sun at the time of the winter solstice. In addition, the summit of Hinoyama (a peak where beacons were once lit, which is visible from all directions in the south-central area of Yamaguchi and which used to house a shrine) lies due south of the stone, while Kasuga Shrine lies due north. (One can infer from a map of the precincts thought to have been made in the Edo period and copied by hand several times down the generations to the Meiji period that in ancient times, this area marked the boundary with the sea.)

If we compare this standing stone thought to have been erected at the intersection of north, south, east, and west with a ground plan of the Yamaguchi Basin, something extraordinary begins to emerge. The standing stone is actually located at the center of a magnetic field reminiscent of Onmyodo ( Japanese esoteric cosmology); the Iwahana stone on the Aio coast, Takuhi Shrine, the summit of Hinoyama, the Tateishi Stone, Kasuga Shrine, the summit of Himeyama, and the Wani Stone (the barrier at the Kushino River) lie on a completely straight line running north from the southernmost stone. This straight line intersects with the east-west highway (the east-west passage of the sun at the time of the winter solstice) at right angles. For the 2014 Research Showcase that formed part of the PPP, we took 360° footage at a number of points on a plane linking these areas of high and low terrain. Then, at YCAM InterLab, we used a virtual reality system to produce a visual system that enabled visitors to experience the feeling of warping freely from one point to another. Another profoundly interesting point is the fact that relics of the urban culture of the Ouchi clan from early modern times onward are layered over these deeper urban structures of ancient societies in the north, south, east, and west. Myokiji Temple (known today as Joeiji Temple), which was the family temple of Ouchi Masahiro’s mother, and Jotokuji Temple both lie exactly on this north-south line and both of these temples that were a key presence in the lives of the Ouchi clan have gardens by the painter Sesshu (said to have been designed by Sesshu). No conclusion has been reached about whether these were intentionally laid out to reflect the sun’s movement through the celestial geography or whether they are the product of chance. However, it is at least certain that there was a common spatial awareness, transcending individual eras, that the basin as a whole was contained in a symmetrical structure with the sea to the south and the mountains to the north.

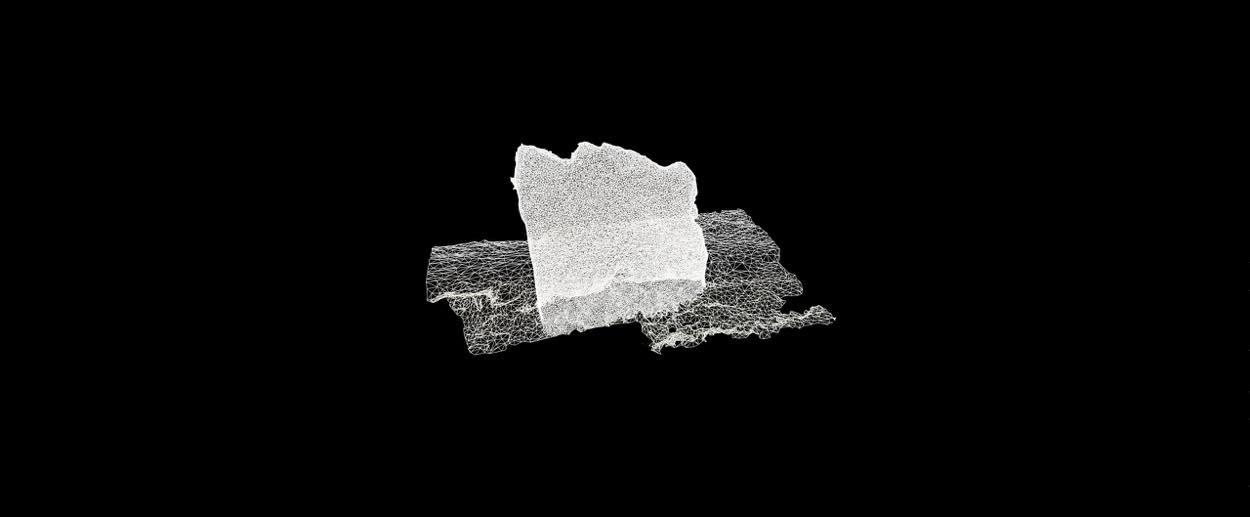

Ouchi Hiroyo’s shaping of the city that became the prototype for modern- day Yamaguchi during the Nanboku-cho period is known to have been based on the Inyo Gogyo Setsu (Theory of Five Elements in Yin-Yang) [a system in which the four points of the compass correspond to four symbolic sacred beasts: east is an azure dragon, south a vermilion bird, west a white tiger, and north a black tortoise] established in ancient China. [The five elements, or five phases, are a concept that Zou Yan, a Chinese philosopher during the Warring States period, blended with yin-yang theory in Yinyang Zhuyun Shuo (The Master Cycle of Yin and Yang). He advocated the Wuxing Xiangke Shuo (The Mutual Conquest of the Five Elements), which regarded the five states of qi (life force) of which everything consists (namely wood → earth → water → fire → metal → wood) as being in a state of conflict. Later, the Han philosopher Liu Xin propounded the Wuxing Xiangsheng Shuo (The Mutual Engendering of the Five Phases), which held that the elements were in a cyclical relationship in which each was successively engendered.] In seeking to gain a spatial understanding of the Yamaguchi Basin as a whole as it was in ancient times and the Middle Ages, one can only imagine the effects of this thinking, but it is almost certain that steps with religious and feng shui connotations were arranged along the north-south axis. Moreover, the common characteristic of almost all Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples since ancient times is a south-facing gate, while the garden-like spaces within their precincts have visual elements that use borrowed scenery (including those needed to be supplemented by the imagination), in which the viewer gazes out from the north toward the sea to the south. Our research also revealed the presence of the Ochakunoishi, a stone thought to have been an object of worship in the mountains about 10km northwest of Yamaguchi Daijingu, a branch shrine of Ise Grand Shrine. The presence of a stone signifies the presence of a spirit or serves as a mapping object, and can therefore raise the question of how it relates to the spatial structures of distant cities and the formation of transport and communication links. We have edited our research into these stones to compile the “Park Atlas,” a data visualization of the PPP.

To start with, we can see a common thread in that, throughout the history of civilization, regardless of era or culture, parks have, via gardens, been associated at a fundamental level with some kind of paradise (Utopia) separate from life here on Earth. This is because, while “parks” are public spaces, they are also devices with a sense of the imaginary or saltatory that dissimilate surrounding environments and contexts precisely because they are enclosed. Moreover, by thinking about parks as such devices of common fantasy, we could well reach a new diachronic interpretation of the relationship between paradise, gardens, and parks. When considering the boundary dividing modern parks from pre-park gardens, one might even apply the concepts of what the anthropologist Lévi-Strauss named “cold societies,” which achieved stability through the symbolism of ancient rituals, and modern “hot societies,” in which such stability collapses and degenerates. Gardens are “cold societies,” whereas parks are “hot societies,” in the sense that they are modern. However, if one examines the garden- like nature of parks, which have an other-worldliness and buoyancy through being separated from the surrounding environment, one might reach the assumption that while the parks that emerged in modern history were located in the vortex of a “hot society,” they had deviated from it to become a channel or zone that reverts to the religious order of a “cold society.”

To decipher the symbols in the city and their topographical lineage, enclosed by a boundary delineated by a constellation of stones, portraying the whole of the wider area around the basin in which Yamaguchi City ─ YCAM’s home ─ is sited as a single park-like concept and examining the meaning of the stones not only in a fetishistic religious sense, but also in terms of their relationship to the terrain in which they were placed and their positional relationship to each other might well throw into relief the multi-layered, multi-temporal thoughts and deeds that have arisen in the city, including a hitherto-invisible sense of community.