A modern artist has to exhaust two-thirds of his time trying to see what is visible ─ and above all, trying not to see what is invisible. Philosophers often pay a high price for striving to do the opposite. A work of art should always teach us that we had not seen what we see. – Paul Valéry, “Variété”

─ Paul Valéry, “Variété”

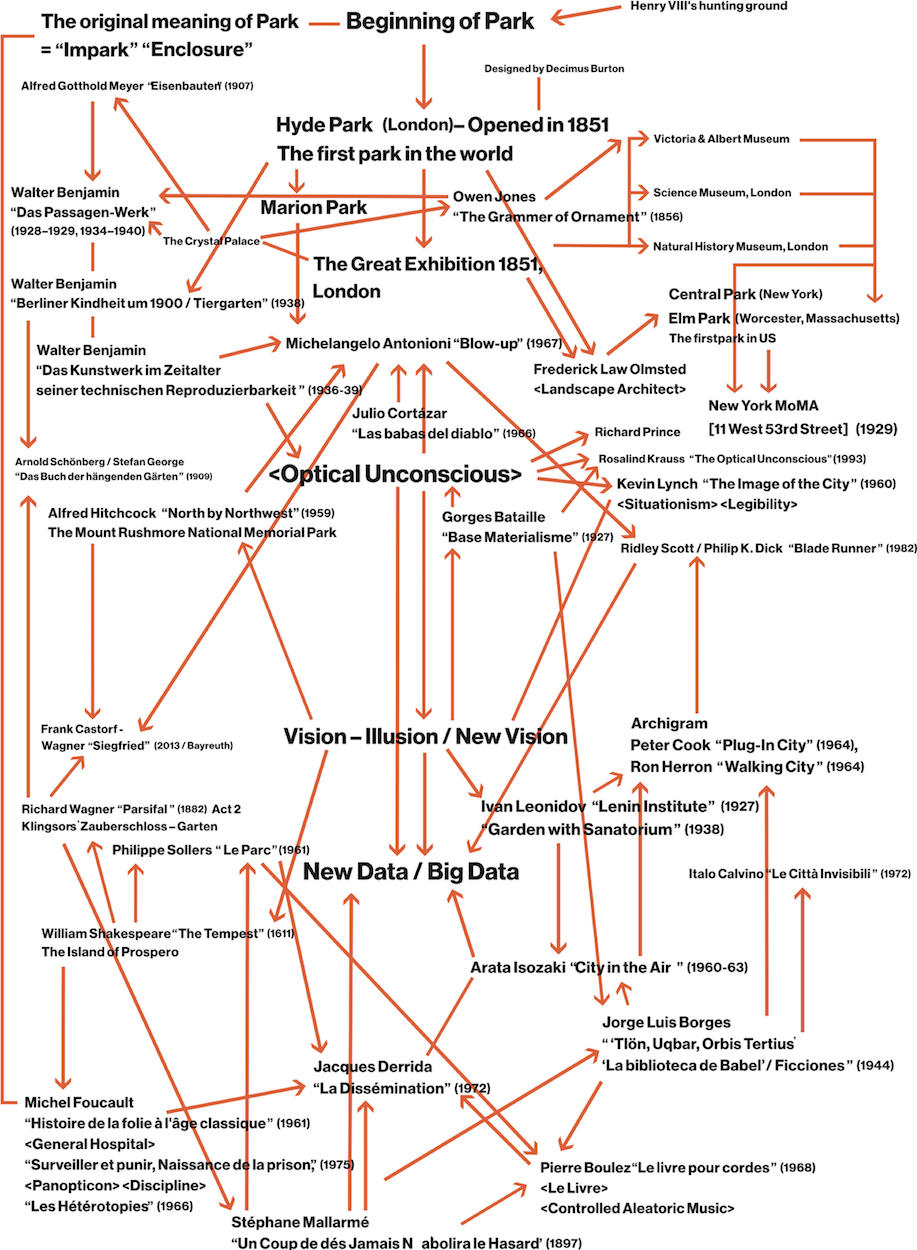

At first glance, the Promise Park Project installations might seem far removed from parks. Ruined relics of early modern industry and a ruined island provided the sources of the images presented in both Carpet of Moving Images and Woven Carpet. the PPP does not make suggestions for the parks of the future based on a realistic urban plan, nor does it focus on sampling the parks of the past. Modern parks emerged with the rise of civil society and they have a history of functioning as a means of covering up the temporal and spatial genius loci that existed in those places. the PPP’s aim was actually to unearth the possibilities for the future from what they had concealed, actively utilizing media technology and biotechnology as well to focus on the visionary network functions of parks as special confined spaces. Parks and gardens essentially differ in terms of the history of their formation, as do their social functions in modern cities. However, from a cultural anthropological perspective, if we trace back the origins of parks and gardens and focus on the aspect of a particular element in shared space = public space being separated as a void from the rest of the space, it is not impossible to end up finding a point that parks have in common with gardens, their precursors in park history. This short, collagesque essay explores what possibilities for reminiscence emerge when examples of confined spaces and folding functions evoked by parks in contemporary history are linked in a saltatory way and their context rearranged. (“Essentially memory is conservative; reminiscence destructive.” Theodor Reik)

It would be fair to say that there is not a city anywhere without a park. This might be because, somewhere in our minds, we associate a park created by enclosing part of a city with a memory of paradise. If we liken a city to the body, parks also evoke a reminiscence of the imaginary, in the form of a womb-like haven. (The opposite of this might well be parks as a pathosformel (“pathos formula”).) To start with, a park itself is a space whose nature clearly differs from the functions of the city around it, where time flows in a different phase. The style within a park is always that of a “park within a park.” Fundamentally, parks are a nested entity. Rem Koolhaas called spaces that continually proliferate and develop without individuality (the majority of modern cities) “Generic Cities” and believe that empty spaces that differed from these were needed, referring to these as “the void.” As Henri Lefebvre pointed out, if we regard cities as “lived space” rooted in physical sensation, urban spaces manifest their significance as something synchronized with our bodily rhythms. In that case, how is this urban void perceived? How is it associated with the body and perception?

What is more interesting in examining the relationship between art history and parks is the question of what saltatory roles and channels do parks, which come into being through the act of being enclosed, set in motion when they deviate from this original function of modern parks and are associated with other spaces and times? Are the devices called parks places where something is stored or buried (“negatives which remain useless because the intellect has not developed them” Marcel Proust)? Are they places that project the things spawned by the maelstrom of creation and destruction? Are they something brought about by force, through the act of being enclosed to separate them from the outside world, or are they something created spontaneously or endogenously....It is necessary to consider them in this multiplex way. For example, William Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1611) could be described as an extremely modern play in structural terms, but the island where Prospero is exiled after being banished by the Duke of Milan is itself a type of imaginary place, which could justly be called a visionary, futuristic device. Interpreting it as something created to produce an imaginary place, rather than as something for a theatrical representation of The Tempest, throws its placelessness into stark relief. In the sense that it is a confined space where an organization that is spatially and temporally different from that of the surrounding city arises, one could hypothetically liken the island of Prospero’s exile to a park. It is home to spirits of the air and magic is made reality there. Prospero can predict the future and manipulate time there. The isolation of exile (hospitals and prisons amid the tide of modernization referred to by Michel Foucault) occurs in the midst of a “hot society”; at the same time, this shows that the humorous magic garden that Prospero controls, which swims against the tide of modernization, has the ritual symbolism of a “cold society.” In the film Prospero’s Books (1991), which could be described as Peter Greenaway’s version of The Tempest, told from Prospero’s point of view, all of the action that takes place on the island of exile is simultaneously three-dimensional and picturesque. Furthermore, Prospero’s magic = media is used to manipulate space and change dimensions, with everything being recorded in virtual books. (Greenaway actually used Hi-Vision video inserts and the Paintbox system, which were advanced technologies at the time, to manipulate digital images.) Although Prospero’s Books has been criticized for focusing too much on picturesque video effects, scenes in the film have been made in such a way that they can be stored separately, further rearranged, and manipulated on the palette to turn them into images, which help to further emphasize the nature of The Tempest as a virtual device when divorced from the overall plot (context). The play unfolds with the symbolism of both a “hot society” and a “cold society.” Shakespeare ultimately leaves the judgment concerning the answer up to the reader (audience).

Let us now leap to another work that is clearly based on The Tempest, Parsifal (1865/1883), the Bühnenweihfestspiel (“Festival Play for the Consecration of the Stage”) composed by Richard Wagner at the end of the 19th century, and let our imagination roam in the gardens of Klingsor’s magic castle, which is the setting for Act 2. If Act 1 and Act 3 are set in an unspecified space in the vortex of a hot society, then Act 2, in which the three unities of theater are ensured, constitutes the insertion of a cold society. A domain foreign to the injured Knights of the Grail = Prospero’s island appears there. (In Wagner’s own set drawings for the premiere at Bayreuth, it is a space replete with an Asian orientalism.) However, looked at through the lens of today’s diverse society, we cannot differentiate between the two perspectives to determine which is the foreign domain, the Christian one (Acts 1 and 3) or the foreign religion (Act 2). Gurnemanz’s words during the Act 1 Verwandlungsmusik (transformation music), “Here, time becomes space” (“Zum Raum wird hier die Zeit”), which marked the transition to a hot society, were reversed by Claude Lévi-Strauss, who proposed that in a demodernized society that has gone past an anthropological perspective, “space becomes time.”

Seeking to restore Bayreuth, the mecca for Wagnerians, after it had been overrun by Nazis during World War II, the maestro Wagner’s grandsons, brothers Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner, revived the Bayreuth Festival in 1951. Wieland himself became a director, presenting a succession of masterpieces, including Parsifal and Der Ring des Nibelungen (1874). The innovative visuality that Wieland advocated completely stripped away any elements suggestive of a specific sense of place from the set, instead arranging enormous disks and plates on the stage in a manner that one could call plate tectonics. In this technique, a number of these plates were combined for each scene and were twisted up and down, and left and right, creating the location of the characters in the spaces between each plate. Bayreuth’s archive of stage maquettes that have survived the years show that prewar sets, whether representational or somewhat abstract, mainly used the architrave cut off by the proscenium arch to represent a natural scene or views within the town or inside a building. The enormous, abstract plates = special virtual device employed by Wieland do not appear.

Wieland seems to have been greatly influenced by Carl Gustav Jung’s archetype theory in the field of psychology. So why did he use these plates? In short, Wagner’s operas are an act of flinging the audience into a place of primitive sensation a world away from the superficial representation of real-life cities ─ a place where we can directly access the perspective on the world on which our society fundamentally relies. Europe’s modern performing art system places great value on greater complexity, pouring in not only combinations of structures and principles, but also mythical things, economic things, and even folksy things, going so far as to add to texts a generative productiveness or sustainability that completely deviates from the classic music framework. Unquestionably, this tendency reached its apex in Wagner. As such, without the introduction of an extreme form of abstraction as a reaction against this, it would have been impossible for the ever-more-complicated Wagnerian opera structure to sustain itself. Regarding direct access to the universe of Wagnerian opera, association (Martin Geck) with the philosopher G.W.F. Hegel’s “List der Vernunft” (“the cunning of Reason”) provided the comprehensive artistry of Wagnerian opera with a sense of unity, but, on the other hand, led to the results that invited the association with the Nazis in the 20th century. Considering this, the world of visual plates introduced by Wieland was a choice requiring a great deal of courage and the use of the plates to turn the stage into a void space is highly critical.

Patrice Chereau’s production of Wagner’s Ring to mark the centenary of the Bayreuth Festival (1976), which reflected social progress since the Industrial Revolution, and Harry Kupfer’s production of The Ring set on “The Road of History” are, in the sense that they abandon symbolism reliant upon Jungian archetypes, a clear rejection and technical criticism of Wieland’s style. However, one could say that these productions, which utilize abstract linkages, leaping from one point in time to the next and mixing eras, have critically inherited the fundamental nature of Wieland’s production, in a sense. (Chereau’s production of The Ring featured industrial machinery beside the stage that was constantly in motion, irrespective of the action unfolding on stage.) Moving forward into the 2000s, the Regietheater paradigm came to the fore: lewd and tawdry, with transposition of settings into contemporary social phenomena or a present-day locale and shot through with satirical sarcasm. The production of Parsifal (2004-6) staged by Christoph Schlingensief at Bayreuth must have been a remarkable achievement within the Regietheater movement. Acts 1 and 3 of Schlingensief’s Parsifal transposed the setting to a refugee camp in the African country of Namibia, with Parsifal depicted as a savior who has the only antibody serum in the midst of a biohazard caused by a retrovirus. In the salvation of the last scene, just like in Peter Greenaway’s film A Zed & Two Noughts (1985), actual rotting rabbits appeared on a gigantic screen. To the sound of a long, drawn-out chord representing the ultimate salvation, the rabbits’ hearts started to pulsate again, the curtain fell, and the audience was dumbfounded. Schlingensief regarded Parsifal as the conflict between a hot society and a cold society, using video media to convey the stirring of life amid this conflict. In Act 2, Klingsor is portrayed as a voodoo priest, performing rites not tolerated by Christian society, but finally, like in Fritz Lang’s film Woman in the Moon (1928), Klingsor dies trying to escape to another world on a rocket.

As shown by Schlingensief’s frequent use of multiple screens, with his emphasis on the spatial-temporal intersection of video over picturesque stage design, the Wagnerian stage becomes closer to a film. (There were constant rumors that film directors such as Wim Wenders and Lars von Trier would be invited to stage Wagner’s Ring, but this did not ultimately happen.) In the production of The Ring staged by Frank Castorf to mark the 200th anniversary (2013) of Wagner’s birth, live footage shot on stage with high-resolution handy video played the main role. Act 2 of Sieg fried contained a reference to the famous gigantic monument featuring the faces of four great American presidents carved into the side of the mountain in Mount Rushmore National Memorial Park in South Dakota. However, rather than being those of past presidents of the United States of America, the faces that Castorf used, which took up the whole of the stage, were transformed into the iconology of communist lineage: Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao Zedong. This is obviously a reference to the Alfred Hitchcock film North by Northwest (1959). (The rear of the rotating stage depicted Berlin Alexanderplatz, which also has links to a film.) Hitchcock’s protagonist (Cary Grant) is, without his knowledge, mistaken for a spy and is thrust into a vagrant existence, his life at the mercy of the ideology between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. For Castorf, this protagonist must truly be a Siegfried for our times, amid the contests to capture energy resources that still repeatedly play themselves out even now, in the 21st century. As is often pointed out, the direction north by northwest has no factual meaning, indicating a fictitious other place. As in the aforementioned Act 2 of Parsifal, Sieg fried, the Second Day (performed on the third night) of the four-part Ring Cycle, constitutes the insertion of a cold society into The Ring. One would have to say that Castorf, who introduced the hollow papier-mâché Mount Rushmore (even North by Northwest was not filmed on location, but rather entirely on a set at MGM’s studios) possesses quite a discerning eye.

As you know, in Act 1 of Sieg fried, the god Wotan appears as an anonymous wanderer; the predictions that he makes to Mime and the appearance of the earth goddess Erda symbolize that Siegfried is a cold society. Thus, one could consider the three prophetesses known as Norns, who appear in the prologue to Götterdämmerung, the Third Day (performed on the fourth night), as an epilogue that constitutes an extension of the cold society of Sieg fried. (It goes without saying that these three Norns are a reference to the three prophetic witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1606/1623).) As Friedrich Kittler points out, it is deeply interesting that Wagner, rather than simply setting a play to music, wanted from the very outset to introduce magic-lantern technology ─ effectively, film ─ to project onto the stage something not actually there to provide visual information as part of his grand opera vision. It was only in the 21st century that Wagner and film-like techniques at last began to show signs of being brought together. This is because, like the cinema that appears at the start of Bernardo Bertolucci’s film Luna (1979), a film is a much more visionary device than a play; indeed, it is a medium of womb-like memory.

Parks as a device are also very important in cinema, which is considered to be the Seventh Art. New York’s Central Park is the place where international spies conventionally make contact, but in Bertolucci’s first film, La Commare secca (1961), which was based on a story by Pier Paolo Pasolini, the setting is a park in a run-down suburb of Rome. La Commare secca is famously an adaptation of Akira Kurosawa’s film Rashomon (1950), with the action transposed to Europe. Kurosawa’s Rashomon, which is based on a story by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, won global acclaim for its depiction of a multidimensional situation in the setting of a Middle Ages period drama. In the film, several people witness a crime, but the statements that they give from their respective viewpoints all differ, contradicting each other and giving rise to multiple versions of the truth. (It became the first Japanese film to win a Golden Lion at the Venice International Film Festival (1951).) Kurosawa chose as the setting for the crime a grove in a forest in the mountains, where the actual location and the situation outside are unknown. Kazuo Miyagawa’s outstanding cinematography, which combines both natural and reflected light (the tracking shots in the forest were actually created by rotating the camera around the same spot several times), gave equal expression to the fascinating nature of the characters. Bertolucci transposes this to a park in Rome in summer and transforms it into a lyric poem that spins together the threads of existence of five people of varying origins, who are at the bottom of the heap in society. The bizarrely multidimensional situation that occurs amid the net of order and legal constraints becomes a reality that arises as a matter of course within the park. The significance of alienating spaces = parks in Europe stands out here.

Michelangelo Antonioni filmed in London for the first time when making Blow-up (1966), which was inspired by Julio Cortázar’s short story Las babas del diablo (1966). The protagonist, a photographer played by David Hemmings, accidentally photographs a murder while walking through a park, triggering a series of incidents. Initially, he does not realize that he has photographed a murder, but once he develops the film in his studio at home, he notices that he has unexpectedly captured a suspicious gun in one of the shots. It was produced in such a way that the whole of the plot was devised by working backwards from the actual fragment of photograph blown up and the appearance of this image. One cannot but describe Antonioni as brilliant for the way in which he perceived parks as places that hide things and condensed events into that situation. (The filming location was not Hyde Park, but Maryon Park in southeast London.) Blow-up can truly be described as the first film to have directly dealt with the visual unconscious of photographic media. It was Walter Benjamin who first referred to the “optical unconscious.” In Kleine Geschichte der Photographie (1931, published in English as A Short History of Photography), he points out, “It is indeed a different nature that speaks to the camera from the one which addresses the eye...instead of a space worked through by a human consciousness there appears one which is affected unconsciously.” The visual media of photographs and video, which are reproduction techniques, physically expose and imprint visual enlargements of details from objects that do not impose themselves on the human consciousness or extensions of time, such as slow motion, as a kind of pattern. Today, optical technology has been digitalized, making ultrahigh- resolution photography possible. As such, when combined with technological innovations such as sensor technologies, networks, new cybernetics, and deep learning, as well as big data, we could be said to have already gone beyond the optical unconscious and plunged into the paradigm of the mediated unconscious, in which there is not even a subject there to see that which is photographed.

Many parks appear in the novels of Marguerite Duras, notably Le Square (1955). From beginning to end, Le Square is written in the form of a dialogue between a man and a woman, and the novel reaches a sudden end when this is interrupted. It has no conventional dramaturgy, just a drifting conversation. The film Détruire, dit-elle (1969) is based on a novel by Duras and directed by the author herself, set in an environment that contains only a tennis court, a dining room, a window, and a garden. In the final scene, an unpredictable catastrophe approaches. It is unclear whether the setting chosen by Duras is a garden or a park, but what is more important is to scrutinize the link between the inside of the room and the space outside provided through the window. In last scene of the original novel, Duras writes, “This music must smash the trees and break down the walls.” However, in the film, what we hear is not music (Duras specified J.S. Bach’s Unfinished Fugue from The Art of Fugue (1742 onward)), but the sound of explosions = vibration. The park is going to destroy the world. The short film Césarée (1979) (cinematographer: Pierre Lhomme; the footage in Césarée consists entirely of unused footage from Duras’ film Le navire Night (1978), which intentionally abandoned systematic camera blocking. Duras said that this was an act of “filming the failure of the film,” in which she arrived at the impossibility of making it) was filmed on location in Paris’ Jardin des Tuileries, home to many statues by Aristides Maillol, and makes liberal use of circular panning shots. Contrasting sounds of Duras repeating “Césarée” and “Caesarea” in her narration and the sense of alienation that this produces are juxtaposed with shifting shots of statues and the park and minimal, monophonic violin music, so that the park space, which in reality should have been an organized system, is rendered disorderly as an individual presence, without any context amid the montage of images. The narration of the text, the images, and the music exist as parallel, unsynchronized entities. The park is a space exposed to something destructive, more so than the urban space outside it. Philippe Sollers’ novel Le parc (1961), whose title itself means “the park,” is a controversial work that presented the disruption of a utilitarian text as écriture. In the elaborate visual depiction sketched out by I appear He and She, but each and every sentence is disruptive and drifts freely as it is asserted, so rather than a dependent, sequential relationship, they have an unrestricted relationship in a mutually nested state. This text is concrete in terms of the links between adjacent meanings, but the overall destination of the écriture is a ramble through a formless space. In Nombres, the exploration of Sollers’ literary space is made at once simpler and more complex. Like the system in Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), each paragraph in Nombres is tagged with a sequential number and the text is a simple ontology in which each sentence stands out equally. None of the sentences have commas. In addition, Nombres contains many fragmentary quotations from Le parc. Even without waiting for Jacques Derrida to mention it in La dissémination (1972), one can clearly see that the origins of Sollers’ work intersect with Proust and also Stéphane Mallarmé’s cryptic poem Un Coup de Dés (1897). As a pictorial representation, Mallarmé’s enigmatic text is, like a constellation depicted on a plane surface, laid out on pairs of consecutive facing pages read as a single panel, with words scattered across the pages in varying typefaces and fonts. The text itself demonstrates that the system produces multiple meanings, whichever temporal channel or detour you follow. Here, not only does the typography have a significant syntactical nature; each character itself contains varying spaces/ margins, producing diverse phases according to the approach (viewpoint). The words divorced from context are perceived visually and their memory constantly galvanizes their existence, so their respective resonance never fades. What turns them into a whole is the confined surface = park-like space on which the characters have been written.

In parallel with Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés, modern composer Pierre Boulez called the concept that made possible a “divisible continuity” “Le Livre (the book).” (Among Boulez’s works is Livre pour quatuor (1968).) Boulez espoused “aléatorique controllée (controlled aleatory),” in which the detailed elements are generative, like the organs within a cell, permitting mutable options incorporating aleatory, while the “Livre” that serves as the overall concept, defining the edges and margins of which they are composed, is clearly prescribed. It is the conceptual frame that permits the coexistence of creation and overall order. The text = music is constantly being written in and proliferating, as a work in progress. (Boulez’s habit of adaptation even extends to the tendency to fully orchestrate his piano and chamber music works to add extra dimensions.) This idea becomes even clearer and more pronounced in his later masterpiece, Répons (1985 onward). Répons adopts a system in which the space functions as a device for adding depth to the potential for the multilayered, nested timbres and acoustic blocks, including distortion from live electronics using a computer, to intersect and explode. A garden-like space within a garden. In this sense, if one were to level a criticism at Répons, one could say that the acoustic space is a nested space created first and foremost not for the audience, but for the performers themselves. Ultimately, the only problem in Répons is the “generative inner space” in which there is no differentiation between the performers and the audience.

In the sense of being a mutant version of Mallarmé for the modern age, the experimental short film Toute Révolution est un Coup de Dés (1977) by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet is an outstanding work. On a hill on an open space in front of Père Lachaise Cemetery, where many of the victims of the 1871 Paris Commune are buried, nine men and women of different nationalities sit in a line facing the entrance, a little way apart from each other, and, one after the other, recite Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés, phrasing it in the way they choose. The single camera changes its position for each shot and the sound was recorded at the same time, so the 50 shots in total (41 of which are shots of the landscape filmed live and 39 of which feature the recitation of Mallarmé’s text) give the work the feel of a montage. Although it is a short film, it has a major impact, thanks to its hitherto-unprecedented approach of linking film, which is a medium based on a sequential timeline, to spaces with continuity in a nonlinear way, by giving them a scattered constellation-like spatiality.

Thai film-maker Apichatpong Weerasethakul has presented numerous video installations and explores video and photography in diverse ways, regardless of the genre of expression. Apichatpong’s film Cemetery of Splendour (2015) features Thai soldiers afflicted with a sleeping sickness. Although they are breathing, they remain fast asleep the whole time and, suffering also from a time loss disorder, do not try to communicate anything. There are eerie curved LED indicators on each soldier’s bed, though what they are linked to and what they indicate are unclear. Only changes in those lights demonstrate that the beings in a vegetative state are being kept alive, indicating the weak and silent rebellion of life, and announcing only invariability and existence. It is set in a hospital on the outskirts of Chiang Mai, in northeastern Thailand, the hospital’s garden, and the park beside it. The film never provides an overall picture of the city, so the viewer discovers only the spatial layout of the immediate surroundings. In fact, it appears that relics of ancient ruins lie dormant under this park. However, under the current military dictatorship, the earth in the park is being dug up randomly, perhaps in pursuit of new economic development in the form of a shopping mall. A number of workers employed by the government subcontractor continue to dig up the park in silence. At the end of the film, a shot of one of the main characters ─ an elderly woman ─ gazing at the pathetic sight of this park signals the close of the film. A reverse angle shot of the elderly woman and the park shows that the earth and sand dug up has been turned into a miniature garden reminiscent of undulating hills, with children from the neighborhood moving playfully around it, for some reason.

Apichatpong’s impenetrability is a gaze that imparts a somehow humorous nomadism to sights that, under normal circumstances, one would expect solely to be burdened with the strength of the ideology of criticism of the administration. Somewhere in there is something also reminiscent of John Ford’s shots of Arizona's Monument Valley. It is a place that Ford used for location filming many times, starting with Stagecoach (1939). Monument Valley too is a type of enormous miniature garden. Westerns are stories set in a confined land, about which only the indigenous Native Americans know everything, in a space dotted with garrisons from which the U.S. cavalry set up in opposition to them patrolled the border. Ford depicted grand battles between the Native Americans and the cavalry in Monument Valley on film many times, but Ford actually looked on the Native Americans with kindness and friendship. He employed them on his films, stimulating economic activity, and also featured them in his narratives. Cheyenne Autumn (1964) depicts the development of the U.S.A. from the perspective of the Native Americans, shining a light on it from the opposite direction. The gaze of the elderly woman in Cemetery of Splendour corresponds to some degree to the sight of Dolores del Río in Cheyenne Autumn. The park dug up in Apichatpong’s film is a miniature version of the landscape in Ford’s Monument Valley (landscapes with a common denominator). The trajectory of the vigorous movement of the Native Americans and cavalry soldiers in Ford’s films is transposed into Apichatpong’s Thai workers as a memory. The representation of this ambivalent, fluid, drifting nature is the best means of expressing respect for the place itself.

In his video installation Phantoms of Nabua (2009), Apichatpong depicts young people who, for some reason, play football with a burning ball on a vacant lot on the outskirts of the village of Nabua (the whole village was occupied by government forces for about 20 years from the 1960s, because the government determined that it was a secret base for communist insurgents) in northeastern Thailand. In remote parts of Asia, which have neither modern urban spaces nor park-like spaces, the vacant lots where common people and children play are a type of park-like void space. In Apichatpong’s Phantoms of Nabua, the ball of fire actually kicked around by the boys finally goes flying toward a screen (the surging flashes of light in the space are actually projected onto it) erected on the field and the screen goes up in flames. Thus, the real (actual scenery) and the recorded/remembered flame (video) melded and were destroyed. Apichatpong has often selected burning objects and fireworks as elements in his recent work. He says that exploding fireworks represent destruction and slaughter by military weapons, while also, in direct contrast, being symbols of the vitality of life and celebrations, which always make an appearance in the festivals of the common people, without fail, serving as a root element linking humanity with the earth. Fully tolerating the ambivalence of existence, opening up the senses as a result of this shock, and the manifestation in the blink of an eye of the passage of time in multi-layered memory that cannot be measured is the resolution of vision = perception that Apichatpong’s works could have, and the sensitivity that we must intentionally summon toward park-like spaces. A scene in the end credits of Cemetery of Splendour shows common people doing group calisthenics to music in a modern urban park. The void that the common people have at last opened up here merges with modern urban park spaces on the screen. In the PPP fieldwork, posing the question “Is it possible to view Tokyo from the perspective of the city as a park?”, we worked with MOON on a study of Meiji Shrine, which has been at the core of the city’s design since the Meiji Restoration, and its surrounding area. The magnificent Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden, located adjacent to Meiji Shrine, housed an Edo period mansion that became a plant testing station before being turned into a garden for the Imperial family in 1906. After World War II, it was opened as a national garden in 1949. The vegetation within is also intentionally very diverse and, as a garden-park, it is a complex space, featuring a traditional Japanese garden, a Chinese-style historic building, an English landscape garden, and a French formal garden with four rows of huge plane trees that create depth by using a perspective called vista structure. Whereas Meiji Shrine is a concealed space with many areas that are off-limits, Shinjuku Gyoen was opened up to be an extensive space for public relaxation, symbolizing postwar freedom.

Mikio Naruse’s film Yama no Oto / Sound of the Mountain (1954), which was based on Yasunari Kawabata’s novel The Sound of the Mountain (1954), contains a famous scene set in Shinjuku Gyoen, which was filmed on location in the French formal garden. This scene in Shinjuku Gyoen also appears in the original book, but Naruse’s film focuses only on the appearance of the vista-structured avenue, changing around events that occur in the original, so that this becomes the climactic scene at the end of the film. In this scene, Kikuko (played by Setsuko Hara), who has secretly had an abortion, exhibits a hint of an Electra complex toward her father-in-law, Shingo (played by So Yamamura). Naruse uses the intervals between the two rows of trees lining the avenue and the depth that the desolate wintry scenery creates to represent the sense of distance glimpsed in the relationship between the two. Skillfully, moving the angle from left to right, he weaves delicate tracking shots and reverse angle shots with directional shifts and changes of focus into a single sequence (cinematographer: Masao Tamai). The discipline of the straight perspective and the dislocation of the characters’ viewpoint as they seek to evade and flee it. That is a distinctive feature of Naruse. The scene is set on a winter’s evening, as in the original book. As you will discover if you actually go there, Naruse ensured that only two of the four rows of trees, which are thought to go on for 120m, appear on the screen, by means of artful cutting and editing. Thus, he pruned away excess to express in an iconic way the taboo love-hate relationship between father and daughter. He represents the stagnation befitting the depth of perspective and, immediately after, the movement into the open plaza, with its view, as elegant movements in space. Shingo declares, “I wouldn’t have dreamed that there was a place like this right in the middle of Tokyo.”

In fact, a few years before Sound of the Mountain, Yasujiro Ozu shot the film Banshun / Late Spring (1949), which also starred Setsuko Hara. It is likely that Sound of the Mountain’s Naruse had a tremendous sense of confronting Ozu, given that both films share the Electra complex of a daughter for her father as a central theme. Interestingly, in both of these world-famous cinematic masterpieces, the garden/park space is inserted as a contrast to the psychological battle between father and daughter in the climax depicting an Electra complex. In Ozu’s Late Spring, the famous vase shot constitutes that scene. A husband has finally been found for Noriko (Setsuko Hara), the only remaining daughter in the family after her siblings died in the war, but she cannot bring herself to get married. Father and daughter go on a last trip to Kyoto before the wedding and, in the traditional inn where they stay, Noriko confesses to her father Shukichi (Ryu Chishu) that she does not want to marry. However, Shukichi pretends not to hear, faking sleep. Shots of a vase in the tokonoma alcove, which has nothing to do with the plot, are interspersed here. These shots have been the focus of a torrent of diverse opinions from across the globe, debating what meaning the vase could have. Let us look again at the order of this sequence. Before this scene, we see the L-shaped stage of Kiyomizudera Temple’s main hall, which cuts into the cliff face, in the Higashiyama district of Kyoto. The perspective switches back and forth between a dialogue sequence “over there” and a dialogue sequence “over here,” creating a deep perspective. After the vase scene, in contrast, there is a scene (a dialogue between the father and his friend, without the daughter) set in the karesansui (dry landscape) stone garden at Ryoanji Temple, a famous temple in the Ukyo district of Kyoto, affiliated to the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism. The Ryoanji sequence is composed of eight shots, with linked close-ups of the stones dotted around the karesansui garden (the sand represents the ocean, while the stones placed amid it represent the high mountains amid the clouds). The composition of the seventh shot is such that the rocks laid out unevenly in the garden appear in the very center of the screen. This more or less corresponds to the tense relationship between the object (vase) and the space around it (the space in the tokonoma alcove) in the vase shots. Ryoanji is the ultimate garden space, compressed into a long, narrow form, with all elements condensed in an abstract way that could well be described as unreal. Ozu links three sequences with extreme changes of tone: (1) Kiyomizudera on a clear day / a space with emphasized perspective / a fulfilling dialogue between father, daughter, and friend (2) a room in an inn in the semi-darkness / a narrow tokonoma alcove / the psychology of an unstable father-daughter relationship (3) Ryoanji in bright sunlight / the oblong shape of the rock garden, cut to remove the sense of space / a dialogue between father and friend, lacking a phallus. In addition, using the shot of the vase (a tokonoma could also be described as a kind of indoor garden space) as a hinge between two contrasting spaces representative of Japan, Ozu connects the two (in the bedroom of the inn, a struggle is taking place to determine whether the daughter’s desires will be influenced by the former (Kiyomizudera: fulfillment) or the latter (Ryoanji: absence) and the strength of the subliminal connections between unrelated inorganic objects (vase stones) convinces us, through the flow of these three scenes, that she will gravitate toward the latter), wrapping up the climax of Late Spring in just a few minutes. Using a Japanese garden space while attempting to express himself within the paradigm of a classic cinematic frame enables Ozu to conjure up a subliminal dynamism.

Ryoanji Temple has influenced numerous contemporary works. Sitting in the Zen Garden at the Ryoanji Temple, Kyoto, Feb. 1983 (1983), which David Hockney produced as part of a series of multiperspective photocollages, is famous, but in the field of contemporary classical music, there is a piece by John Cage called Ryoanji (1983), which represents the 15 stones of varying sizes laid out in the rock garden as spatial notation. Analysis has revealed that the stones in this rock garden created in the mid-15th century were laid out according to an elaborate algorithm, with each stone’s position in respect of the earth precisely determined and informed by feng shui. This is undoubtedly one reason why this rock garden is still the focus of awestruck gazes even today. The rock garden is a space for reminiscence. Finally, let us touch upon the relationship between the problems of ruins and revegetation, to which MOON Kyungwon has repeatedly referred since the outset of the PPP. Among the short manga created by manga artist Fujio F Fujiko in the 1970s is Midori no Mamorigami (“Midori’s Guardian Deity”; 1976), which was later turned into an anime. In the story, some kind of impact causes an airplane to crash in the mountains and when the protagonist Midori wakes up, she finds that only she and one other person, a boy, have survived. The two of them head for a city, but the unfamiliar jungle seems to go on forever, with no sign of any urban areas. When some buildings at last appear, they discover that it is Tokyo, overgrown with vegetation, but without a human, animal, or even insect to be seen. The manga depicts a world in which all organisms other than plants and bacteria have been rendered extinct by a pandemic caused by the accidental firing of a biological weapon. The manga depiction of a jungle-covered Tokyo actually looks more real than anything achievable with CGI or montage photographs. Although Midori no Mamorigami presents a world that should seem gloomy and apocalyptic, it is a work that somehow leaves the reader with a lingering sense of regressive exhilaration. Envisaging Tokyo, the city as a garden without people. Plants woven through space and time. In the world depicted in MOON’s PPP installations, a post-Fukushima (2011) world (MOON actually went to the Tohoku region to report on the March 11 disaster), no people appear, for some reason, and CGI is used to depict the rooftops of ruined modern buildings connected (vegetatively) to each other, in a landscape where the only development is that of the vegetation. Rather than being visionary, this might actually be a semi-real perspective on the world. Let us ask ourselves again what possibilities exist for parks in this landscape.

The Continuity of Parks (Cortázar) is suspended throughout the history of art.