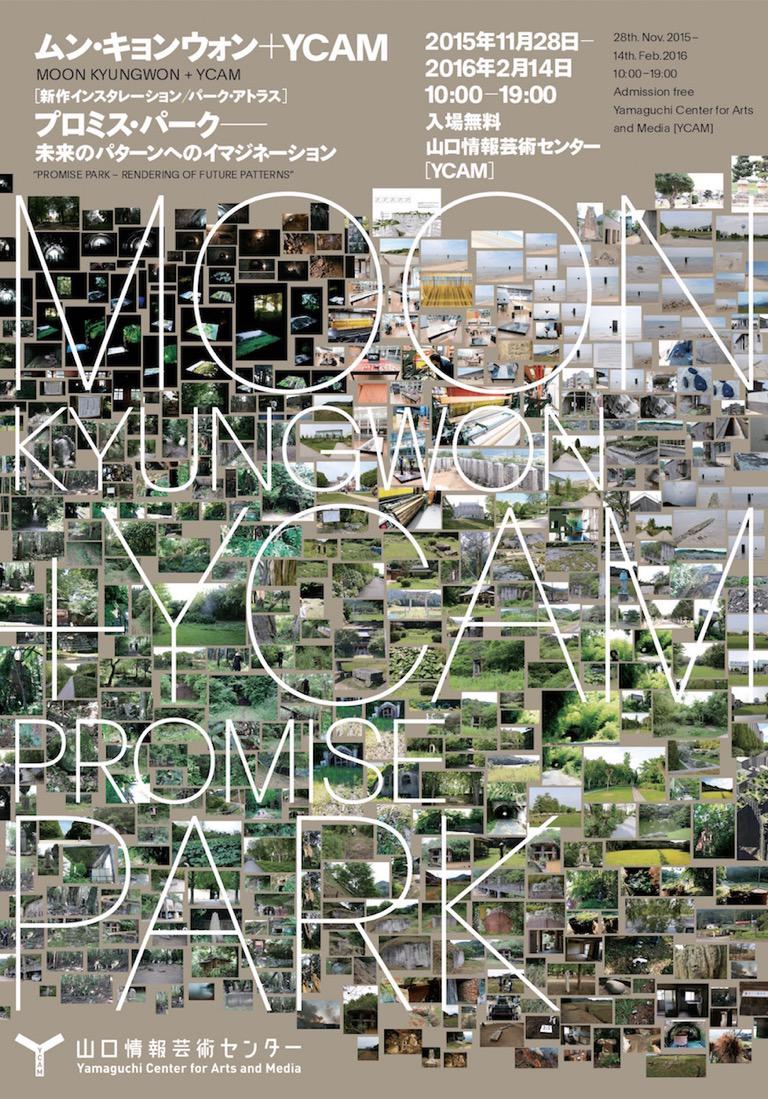

IDAKAThe Promise Park Project was conceived in 2013 as a three-year art project to consider the future of public parks. A collaboration between MOON Kyungwon and YCAM, the project consists of both an initial exploratory research phase as well as the creation of an art installation component. A comprehensive, large scale exhibition will run from November 28th 2015 through February 2nd 2016 as a final concretization of the project.

Although the project is slated to continue developing in the future, the YCAM exhibition presented a prime opportunity to conduct today’s talk event. Without further delay, I would like to first turn the floor over to MOON Kyungwon as well as our guest, architect Toyo Ito, for a brief explanation of their respective endeavors, followed by an extended talk session in the second portion of today’s event.

MOONThank you all for coming today.

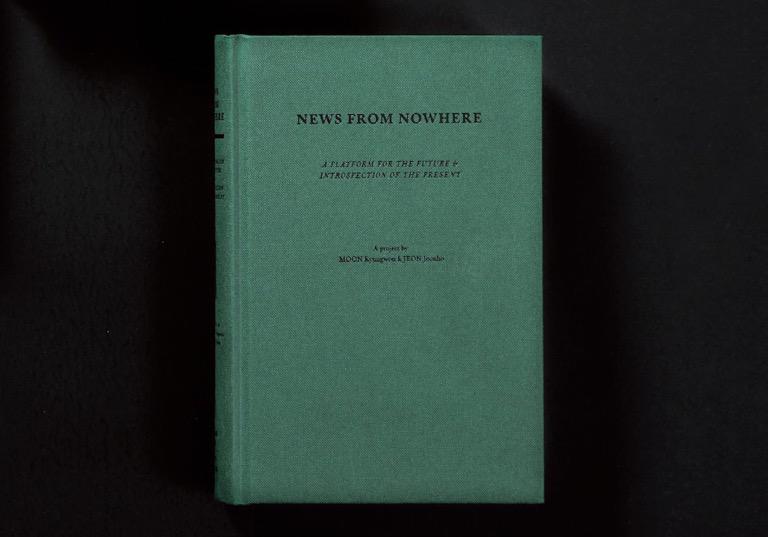

I have always been interested in the relationship between the individual and history, between the individual and society. Focusing on the myriad collisions and phenomenon born from such relationships, I’ve then asked the question: What can art do in response? This query has been a longstanding theme that I’ve grappled with personally. On the other hand, I’ve also been collaborating with the South Korean artist JEON Joonhoo since 2009 on a project called “News from Nowhere.” The project started from exactly this question, this own personal inquiry into the role of art, and has become a platform to research further considerations, such as: How much utility does art offer in terms of an individual’s life? Furthermore, what kinds of social functions and roles can art achieve? The News from Nowhere project was first debuted in 2012 at dOCUMENTA ( 13), then taken on the road to Chicago in 2013, and Zurich in 2015.

It was through this collaborative process that I met today’s guest, Toyo Ito. He was kind enough to oblige our invitation to the exhibition, and came to visit us at dOCUMENTA. I would like to take this opportunity to thank him, again.

Moreover, JEON Joonhoo and I participated in the Venice Biennale as representatives at the Korean Pavilion (2015). By engaging in these collaborative projects, I find that I’ve also become more passionate about my own work. Having then participated in YCAM’s 10th Anniversary program (2013), I became involved in the Promise Park Project, and was fortunate to have spent the past three years working alongside the YCAM team.

When I joined this project, I asked myself the following question: “What form will parks take in the future?” As cities modernize and develop, residents create parks as manmade clusters of nature. We incorporate nature into our cities, and in so doing imbue our cities with icons of a distant spiritual realm. I realized that perhaps this is the essence of parks as symbols. I believe that parks are an individual’s utopia, the embodiment of an ideal. Throughout the course of human history, I think that of all sites, it is parks that reflect the ethos of any given era.

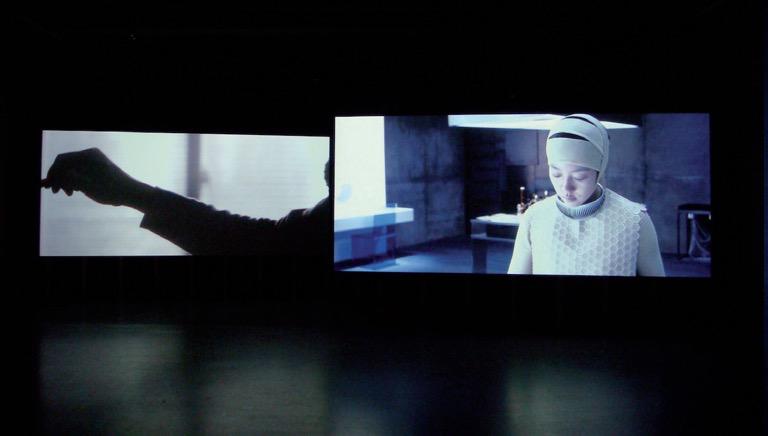

I also felt that, in its purest incarnation, a park also embodies something of an innate humanism, a spirit of resistance that pushes back against civilization. These notions informed the project’s inception. In the wake of civilization’s total collapse, when the world amounts to an abandoned ruin, what form would future parks take? While this is admittedly a very abstract question, I approached it imaginatively, and created the first film (Promise Park, 2013).

Parks begin as an individual’s idea of utopia, but then become a public space, a site that fosters interpersonal communication. Furthermore, parks also facilitate a relationship between man and nature. As such, I thought that I might be even able to explore the existential reality of man existing within a park, and first drafted an indeterminate, uncertain park. This resulted in the video that I made when I first joined the project in 2013, and was the outgrowth of my initial vague approach that was developed and refined over the course of research conducted together with the YCAM team.

This is the exhibition held in 2015 as a research showcase.

Next is an image of one page from Fujiko F. Fujio’s short manga, “Midori’s Guardian,” published in 1976. I was introduced to the manga during the research process, and it came as quite a shock. The park of the future as drawn by this manga artist back in 1976 was extremely similar to what I had envisioned.

I think that I gained two insights from this research.

First, I realized that perhaps my perspective on things has changed due to the evolution of technology. During the research stage, we utilized drones as an omniscient observer capable of surveying abandoned ruins from far overhead. A bird’s-eye view is quite different from the perspective of someone approaching the same site on the ground. I think this difference of perspective dictates how we think about a site.

Second, I came to consider the manifestation of errors on a historical scale. It occurred to me that humans have doggedly pursued a vision of utopia, yet once a park falls into disrepair, it conversely becomes a dystopia. Perhaps this transformation has become a cyclical pattern repeated over and over throughout history. While not visibly tangible, it is a pattern of mistakes that we have historically been wont to repeat, and is evident in an existential form.

I plan to enlist two methodologies to exhibit Promise Park: a film and a carpet.

What led me to create this carpet? I think that the act of weaving a carpet is an apt metaphor that reflects a myriad of symbolisms. It’s a matter of evoking the cohesiveness of the ruins that we researched and fleshing out memories of the past as a means of healing and encouraging regeneration.

Additionally, the act of laying out a carpet equates to transforming that site into a platform. It allows us to modify the character of an extant site, and create a park out of the exhibition space. This also allows us to influence the mindset of visitors to the exhibition. Furthermore, I realized it would be possible to invite visitors onto the carpet itself, in effect transforming the carpet into a site for new interaction and communication. This signifies how, by turning ruins into a park, it’s possible to once more summon a crowd to the site. As such, I want to make it clear that Promise Park is not a project with a one-month expiration date, but rather an ongoing endeavor that will continue to develop and evolve going forward.

This new symbolic platform – an amalgamation of parks as multifarious symbols – will be expressed in the form of a carpet, displayed within an art museum. While this object does suggest future parks, it should not itself be taken as a utopian proposal. “The carpet is a conceptual tapestry” that can be understood in geological terms as the cumulative sedimentary deposits of history to date. In other words, this conceptual tapestry provides a medium for us to conceive of the park-asutopia. It signifies one vehicle by which to conceptualize this ideology.

Unfortunately, there isn’t enough time during today’s event to fully delve into the project in more concrete detail. However, in short, the piece will be installed in YCAM on November 28th as the result of my creative faculty as an artist.

IDAKANext, I’d like to ask Toyo Ito to introduce his own project in dialogue with Ms. MOON’s presentation. Mr. Ito, the floor is yours.

ITOMs. MOON treated us to quite a beautiful and in the same breath, abstract presentation, which I suspect conjured a wide range of associations within everyone here today. That said, the discussion ventured into the realm of imaginative fantasy, a few steps removed from reality. As such, I would like to discuss how we can once more tie these themes back into real world applications.

First, I’ll begin by explaining how I came to meet Ms. MOON. As she mentioned, I was asked to contribute the “Home-for-All”project back in 2012, when she was exhibiting at dOCUMENTA (13). At the time, I didn’t quite see how “Home-for-All” fit into the exhibition, and approached the project with some trepidation. However, after listening to her presentation today, I feel that I finally understand how these projects gel. Ms. MOON’s discussion of ruins just now jogged a mental connection, and I see a link with the towns that became uninhabitable in the wake of the 3/11 tsunami, akin to the abandoned ruins she cited. I wanted to find a way to lend some assistance to these devastated towns, to provide some inertia with an eye for the future. In particular, I made repeated trips to a town called Kamaishi, but was ultimately unable to do anything. The residents of Kamaishi have always lived in their town alongside an unbroken history of land inherited over the ages. It’s a way of living that differs from modern dictums, and I was unable to bridge that gap. Indeed, it’s an example of another problem facing our times: the ongoing squelching-out of history wrought by the goliath strength of modernity.

For example, we now have seawalls, these monstrous coastal barricades that use staggering technological skill to conquer nature. Kamaishi spent thirty years erecting a massive seawall facing its central bay, yet the entire fortification was wiped out in an instant by the 2011 Tohoku tsunami. Despite this, they are now trying to reconstruct the same exact seawall. Why? In the background of this attempt is the utter confidence in this ideology that humans are capable of conquering nature.

However, even if they were to construct a new seawall, the townspeople certainly cannot reside in the areas breached by the 2011 tsunami. As such, all the residents were corralled up to temporary housing at higher elevations. Public housing then becomes available in a matter of two or three years. These public housing facilities are themselves the epitomic product of modernity. Essentially, they are simply a pile of boxes, stacked one atop the next.

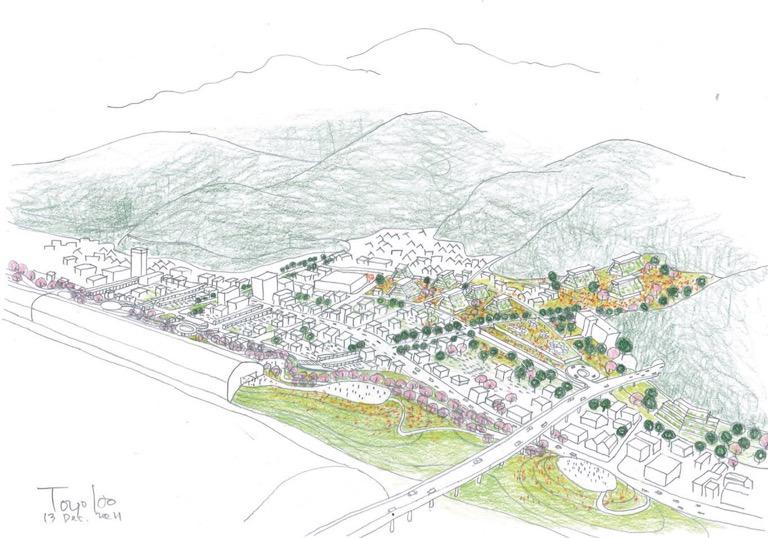

We felt that, if they are going to go to the trouble of building a seawall, they might as well make one that resembles a park. Even where public housing is concerned, surely it’s possible to fashion public housing informed by that locality’s inherited history. We tried to draft any number of proposals to this extent, but ultimately, were unable to bring anything to fruition. At the time, the only thing that we were able to do was the “Home-for-All” project.

The municipality only provided us with the land, so we collected donations ourselves in order to create some ten-odd “Home-for-All” projects. While it’s not a park per se, the project still amounted to something of a park of the future, rising amidst the ruins. In the context of Ms. MOON’s presentation, I was able to make a connection between the “Home-for-All” and future park projects that both emerge from ruins.

I was struck by the interesting ideas included in Ms. MOON’s presentation, which provides much food for thought. I would also mention that the materials provided by YCAM for today’s event were also rich with engaging text. One particularly vivid line read, “Parks and gardens compress a range of scenery into a given space, and are thus a sort of deep freeze apparatus.”

I find that the word “garden” lends itself to far more diverse associations than the word “park.” As an architect, I would always like to make something akin to a Japanese garden. You’ll find a pond in the very center of a Japanese garden, surrounded by tea-ceremony rooms, rocks, and special trees, designed as a course for the visitor to amble about. This layout stands in stark contrast to Western gardens. Your individual experience of the garden space materializes based on the route of your choosing. Personally, I always want to create free architecture without walls. This is because I believe that my own architecture resonates with the linguistic space of the Japanese language.

The Japanese that we speak brims with excess space in the individual partitions between words. This leads to expansive ambiguity, and produces infinite nuance. The reader discerns this nuance, and the speaker layers on words to generate this infinite void.

Yet, perhaps sadly, architecture absolutely demands the construction of walls. This raises the issue of “inside versus outside,” as we must place a demarcating boundary somewhere. I always regret the necessity of this border-drawing.

Please take a look at my firm’s design for Sendai Mediatheque. It consists of 50-meter square planes supported by 13 tubular structures. The function of each tube is distinct, but if I were to compare these tubes to trees, the effect is precisely like walking through a 13-tree grove and being able to use the empty space between trees as you please. When the south side is warmed by the sun’s rays, everyone will gather toward the south. You might find that the shaded north is more amenable to couples who want to enjoy a meal in relative privacy. These types of location-dependent characteristics emerge organically. It’s the same mindset as the Japanese garden. In theory, the space continues indefinitely.

Yet as actual plots of land have definitive boundaries, if we were to metaphorically cut a slice at that borderline, then that cross-section becomes the façade.

IDAKAToyo Ito’s comments are very apt. As he pointed out, MOON Kyungwon’s approach is extremely befitting of an artist. She launched the Promise Park platform in the form of an imaginary, floating garden as a deft aggregation of many people’s visions of the future. I think that this distinction is at the heart of this project.

In juxtaposition, Toyo Ito’s approach is extremely befitting of an architect, as he discussed the nuances of spatial planning in concrete terms. While both approaches do share conceptual commonalities, we were treated to a difference in perspectives, and I believe that both presentations have much to offer as we think about the Promise Park project.

As a next point of discussion, I would like to pose the following question to each of our speakers: When you think about parks of the future, what kind of platform comes to mind?

I’ll ask Ms. MOON to respond first, incorporating your thoughts on Toyo Ito’s presentation.

MOONAs a youth, I also had great admiration for architects. Mr. Ito is a visionary who practices architecture fully mindful of the people who will live and breathe inside his buildings.

When I think about what I can do with my creative faculties as an artist to find ways to connect with society and breathe the same air, I feel that Toyo Ito’s work sets a fine example that offers much for me to learn.

As for the park of the future project, I do think that my work could be viewed as an extension of the garden concept that Toyo discussed. If a garden is a repository for an individual’s thoughts, then I would say that a park is an amalgamation of multiple gardens that, through addition, has experienced a conceptual development from the private to the public sphere.

Moreover, the notion of a “park of the future” is itself a derivation from reality, so my present work entails rethinking what parks might look like in the future from the perspective of the reality that we are presently living. As Mr. Ito said, it’s not a matter of wholly razing the parks and architecture that have long existed on a site, only to spontaneously erect something new in their place. What constitutes a park? I feel that parks inherit a certain historical part and parcel, then evolve by adding an extra layer on top of this history. Furthermore, the gaps he mentions exist dually on a spatio-temporal basis. In other words, excess space that exists “spatially,” so to speak, also exists as gaps on a conceptual temporal scale. Therefore, I thought that we might be able to draw out some further possibilities from this duality.

IDAKAI would like to hear Toyo Ito’s thoughts regarding the Promise Park as a platform. Personally, I think that Promise Park is a highly abstract platform. Rather than having some kind of concrete social impact, I suspect that it will instead attract and consolidate the creativity of researchers and artists at a level one rung higher than society at large.

How do you think that this sort of platform could be developed when contemplating public spaces of the future?

ITOI didn’t have an opportunity to view the project’s Research Showcase, but that said, do think your decision to focus on rocks was truly interesting. Wherever you visit in Japan ─ whether bustling tourist area or small country town ─ you are guaranteed to encounter rocks and stones that seems to have been deliberately placed with a wide variety of meaning. For example, at one shrine, there’s a ceremonial stone, and apparently just by looking at this stone you will be ensured safe childbirth. I thought it was extremely interesting to see such an ethos overlap with Ms. MOON’s film in particular and the project in general.

Although the topology is utterly different, the architecture world has experienced a recent interest in collaboration among groups of people from disparate backgrounds, and work to weave all of these genres togethers as if creating a textile. Even if I were the designer, the truth is that the process is a collaborative effort by a multi-person team. In that sense, we can expect an increasing application of technology in both the art world and also our own world.

I would also point out the remarkable novelty of Ms. MOON’s decision to create a carpet, given her background in filmmaking. HOSOO ─ the stalwart textile-firm in Nishijin, Kyoto that collaborated to create the carpet ─ is a traditional textile maker, yet they are now developing new cutting-edge technology that can even produce this degree of thick, collage-like, entire city of a carpet. I was also very interested in the concept of having the carpet grow with each exhibition. Carpets are portable and can be transported anywhere, so I would like to see it put inside some of my architecture. It consolidates an entire future park. I can see how it is indeed a form of cryopreservation.

My understanding is that the concept of a park was imported into Japan along with the modernization that occurred following the advent of the Meiji Era, so I see a significant distinction between parks and gardens. When I think of parks, the first thing that comes to mind is Yukio Mishima’s essay, “A Defense of Culture,” which contains the phrase, “...like a fountain in a public plaza.” Mishima used the phrase to signify culture that had “been made into something harmless and pretty,” or in other words, had already run dry. Nowadays, most of Japan’s public parks are nothing more than the fountained plazas that Mishima described. So the concept of a park is not something that clearly resonates for me. Gardens, on the other hand, are rife with meaning and association. This was something that came to mind during the presentation.

MOONNow that you mention it, although I’ve been using the word “park,” I agree and suspect that the word reflects a concept that entered or was imported from the West in the wake of modernization. Essentially, a park is an artificial, manmade space.

However, I think that the language used in our ongoing Promise Park project is close to the concept of a garden as explained by Mr. Ito. In short, it starts from an individual level, and the amalgamation, this emotional thought, this private space, is how I conceive of the Promise Park.

In the course of this project, while I have been very happy to have been able to translate my vision into a physical, viewable form, today’s talk event made me realize for the first time how glad I am to also have met Toyo Ito and the many other likeminded people on the project.

ITOThank you. I was also able to think about things in a new light during today’s talk. For one, it struck me how the carpet discussed a moment ago is exactly like a geological layer. In cities like Tokyo, our skylines are now steadily being taken over by skyscrapers. However, if we so much as scratch the surface of the ground under our feet, we’ll encounter layer upon layer of history. I was left with the impression that your carpet is what would result from sampling all these layers.

Another thought that occurred to me is how ashamed I am that we were only able to implement the “Home-for- All” projects in the Tohoku region. I realized that I would like to try and push the envelope a little further somewhere that wasn’t in the disaster area, and have recently been making trips to Omishima, an island in the Seto Inland Sea.

I never had a chance to visit Omishima until a decade or so ago. Although it is an extremely small community, the city built an architecture museum there for me (Toyo Ito Museum of Architecture, Imabari). It seemed like a good time to visit the island. When I went, I discovered that the scenery was immensely beautiful, all orange groves, devoid of the modern. Furthermore, there’s a small, almost communal coastal village on the island, resembling those outcroppings in the Sanriku region hit by the tsunami in northeastern Japan. The island is the kind of sleepy locale that will remain dormant unless someone arrives to take action. I think that I would like to introduce some new, small measure to see how the island will incubate the project and change ever so slightly.

Up until now, I’ve occasionally toyed with small ideas, such as creating “Home-for-All” on the island, or trying to turn the orange fields into a winery. But today’s discussion has made me realize that my endeavors there might have slightly more significance than I initially anticipated. In other words, I’ve begun to envision the entire island as a future park/garden. This doesn’t mean that I will be imposing any kind of master plan for the island. Rather, I’ve begun to think that by simply perceiving of the entire island in such terms, it might be possible to calibrate my previous ideas for the island to think on a larger and more vibrant scale that would combine multiple small little threads moving forward.

Incidentally, Omishima is close to YCAM, so I would be happy if this event encouraged some form of communication and exchange with the island.

IDAKAThank you for the very engaging discussion. As touched on by Toyo Ito, parks exist within this project as a space that, in a sense, creates continuity out of the intermittent, bridging what could be called the interruption between pre- and post-modernity. I believe that the common denominator of today’s event was the question of how to envisage parks and develop them in the future as one platform for public space.

There is still clearly much more room for discussion, and Promise Park itself will surely continue evolving over the years to come. I hope that you all will visit the exhibition space to experience for yourself the project’s staggering past archive as well as MOON Kyungwon’s proposed park of the future.

In closing, thank you both again for the wonderful presentations and discussion.

(Text : Yoshi Tsujimura)