Tell us about Hosoo Co., Ltd.

Nishijin is a special yarn dyeing and weaving technique developed over 1200 years ago. Even now, it’s strongly associated with obi (kimono sashes). During the 1,000 years for which Kyoto was the capital of Japan, it was woven to order by craftspeople in a cottage industry setting and supplied to a limited range of clients in the upper echelons of society, such as the Emperor, aristocrats, the Shogun, and temples and shrines.

Hosoo was founded in 1688 and was originally a manufacturing wholesaler, making our own kimono and obi, and wholesaling high-end kimono and obi, including some made by Living National Treasures.

Tell us about Hosoo’s new business initiative.

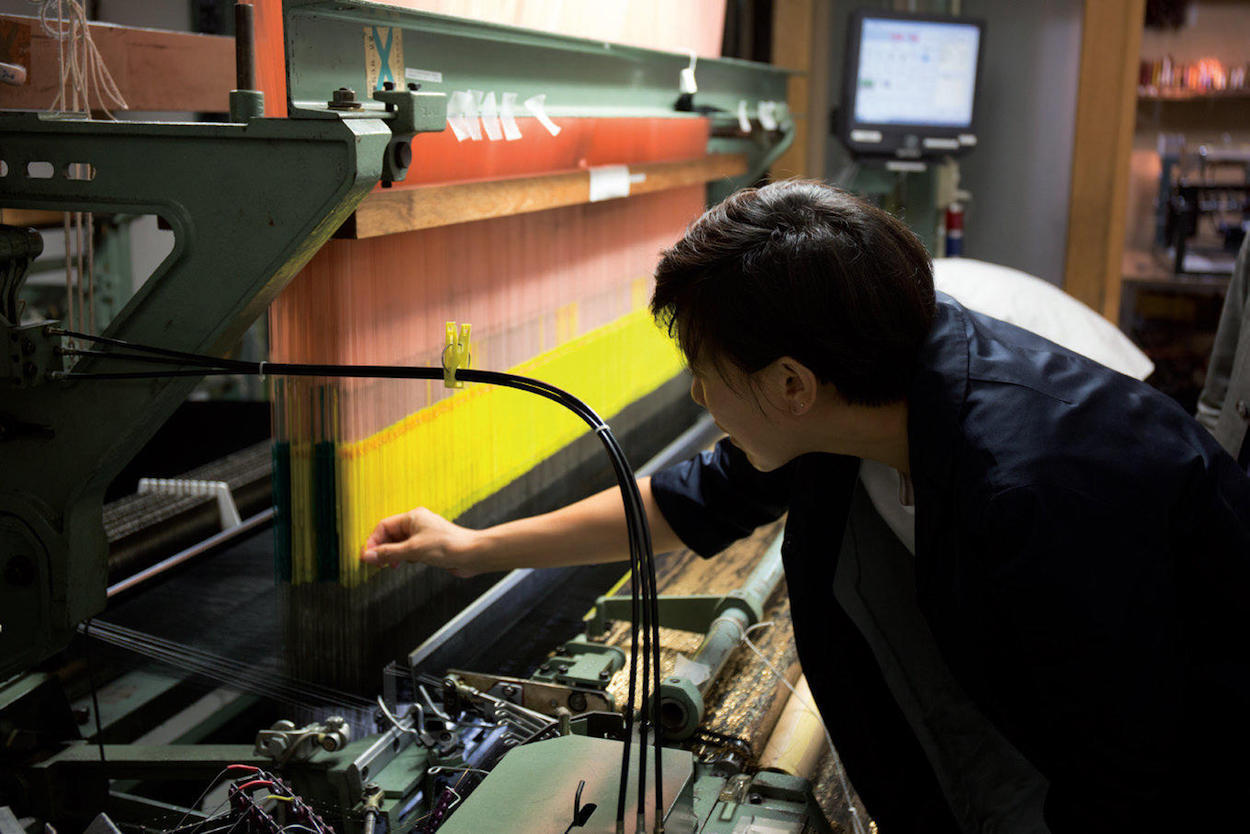

The new business initiative that I am overseeing was launched seven years ago. It involves marketing Nishijin textiles as interior fabrics, mainly to overseas markets. Obi are, on average, about 31 centimeters wide, which is very narrow, so in using fabric of this width, there would have to be many seams, whether you use it to make clothes or wallpaper. That’s why we spent about a year developing a loom ─ the only one of its kind in the world ─ capable of using Nishijin weaving techniques and materials to produce fabric 150 centimeters wide. This is now the mainstay of our new business initiative and we’re taking up the challenge of expanding into entirely different fields, including interior décor, fashion, and, most recently, art projects.

What were your impressions of Promise Park?

To be quite honest, at first, I hadn’t a clue what direction it would take. But that’s exactly why I was hopeful, feeling that we might be able to achieve something that had never been done before.

I have the impression that in interior décor and fashion projects, you just need to get over the arbitrary line regarded as the pass mark for success, whether that’s 90% or whatever. But with art projects, it’s all or nothing ─ 100% or 0%. To put it another way, the key characteristic of art projects is that you have to start by searching to find where your goal lies. In that sense, my impression is that Promise Park started out in total darkness, without a glimmer of light to lead the way.

What was the biggest challenge Hosoo faced in this collaboration?

We used a unique piece of software to convert a graphic image produced by Ms. MOON into a format suitable for Nishijin weaving. It’s probably the first time in the 1,200-year history of Nishijin fabric that something like this has been done.

Ultimately, we managed to produce an enormous carpet measuring 17 meters by 17 meters, consisting of multiple 150-centimeter-wide sections joined together. When laid out on the floor, it forms a single huge picture. This, too, was something that we’d never done before. I think this is a project that you could not have been done without skillfully blending the latest technology with the traditions cultivated over the centuries through to today.

Tell us about the potential for media technology and traditional crafts to collaborate and progress.

I think traditional crafts have a rather conservative image, but in fact, Nishijin weaving has continually evolved by constantly incorporating cutting-edge technology.

For example, up until the latter half of the 19th century, Nishijin weavers used takahata looms ─ horizontal looms with foot treadles that the weaver used to raise and lower the warp yarn – but then Jacquard looms were introduced to Japan. The community of weavers imported the state-of-theart technology of the time, which you could even be described as a prototype computer, and set about combining and blending it with what they had achieved up to that point. In that sense, I think Nishijin has an unbroken tradition of collaborative endeavors of this nature.

For a tradition to go on being a tradition, it must progressively incorporate the new. Indeed, I think the strength of traditions lies in the fact that they’re strong enough not to collapse when something new is introduced, so I want to keep developing edgy projects.

What feedback do you have based on this collaboration?

When collaborating with artists, we find ourselves getting thrown curveballs from angles we’d never even thought of. That’s why, in some respects, it is very hard work, but this also allows us to gain new perspectives, so it’s really meaningful and gradually activates braincells that we had never used. I want to carry on doing this kind of thing and stimulating the further development of textiles.

What subjects are you interested in right now?

I’m very interested in biotechnology. I’m also fascinated by how material (in the true sense of the term) is made; for example, sericulture. I want to work with various research institutes on basic research and other initiatives, so I can create new textiles.