Promise Park ─ Rendering of Future Patterns

- Date: Nov. 28, 2015 to Feb. 14, 2016

- Venue: Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Two Carpets and Park Atlas

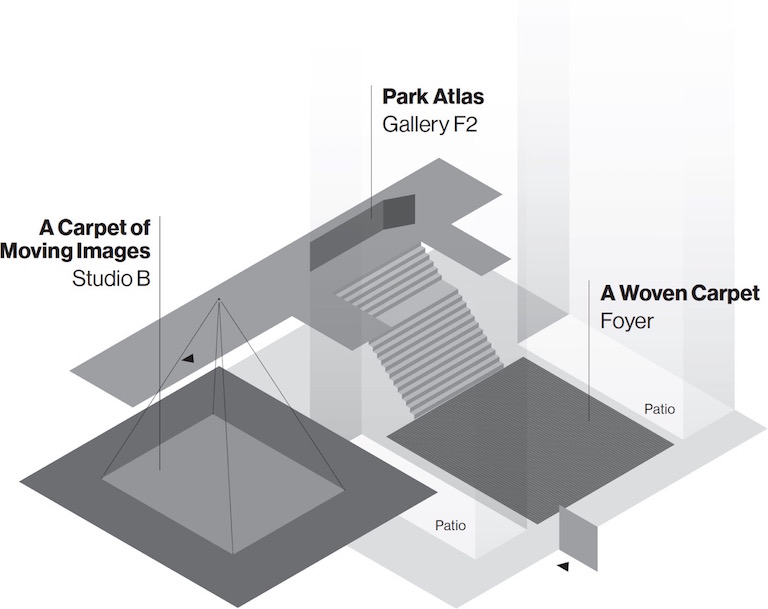

In 2015, two new installations and Park Atlas (an archive of parks) were exhibited, marking the culmination of three years of documentary research and fieldwork.

When confronted with a vast database, we cannot always rely on human knowledge and perception. Perhaps we can find a solution in cultural phenomena from various ages in history. Promise Park focuses on the concept of “Shukuchi (folding space),” associated with Taoist thought, to imagine abstraction of information and quickly changing connections, and the metamorphosis of patterns and textiles as a bricolage – a multilayered construct, which is abstract, minimal, and floating, that is transformed into a two-dimensional plane.

Textiles, a combination of the binary elements of warp and weft, serve as a potent symbol, triggering a connection between the archive, and the human body and perception. Parks and gardens are devices for compressing and freezing various landscapes, and the East Asian garden can be seen as the ultimate in abstraction and compression. It is also notable for its use of folding space. Moreover, a carpet can be likened to a moveable garden or park.

Related article

A Carpet as an Artistic Medium [KAZUNAO ABE]

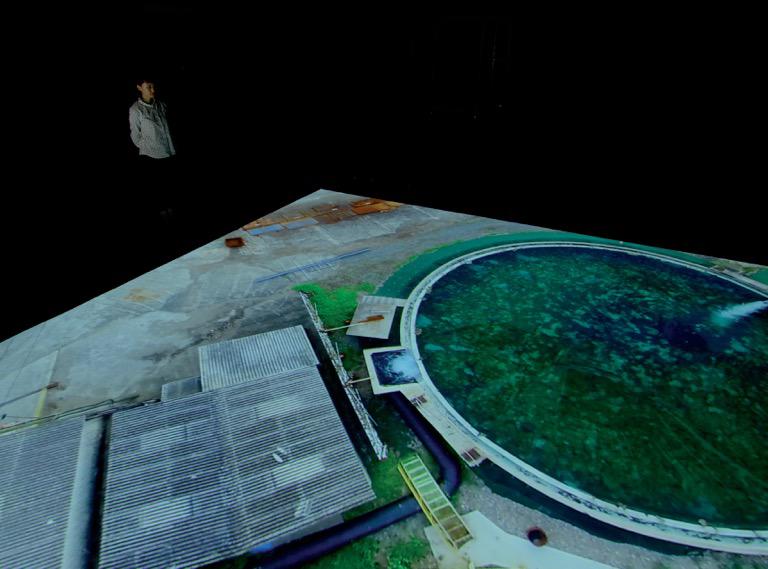

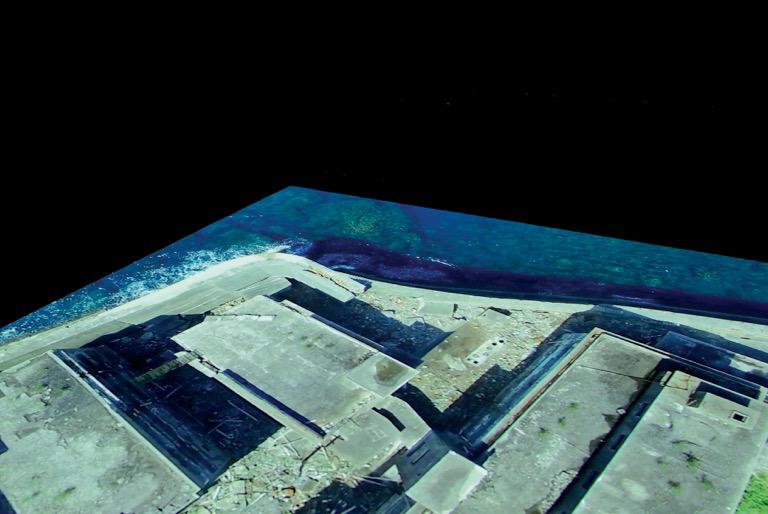

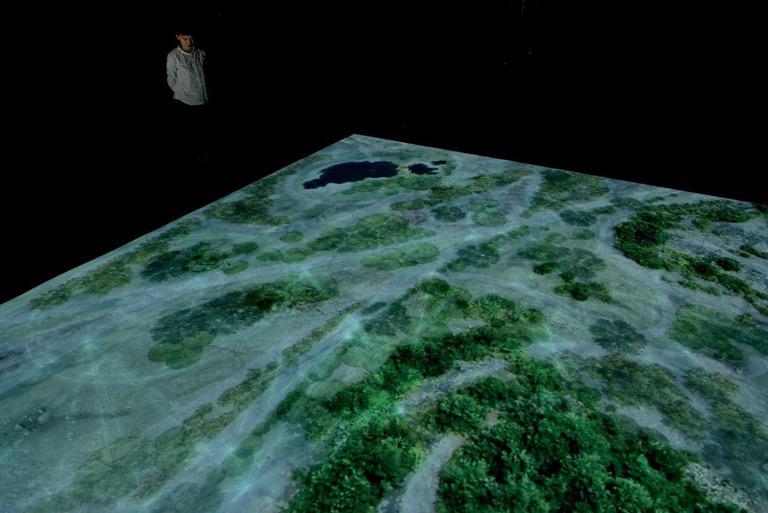

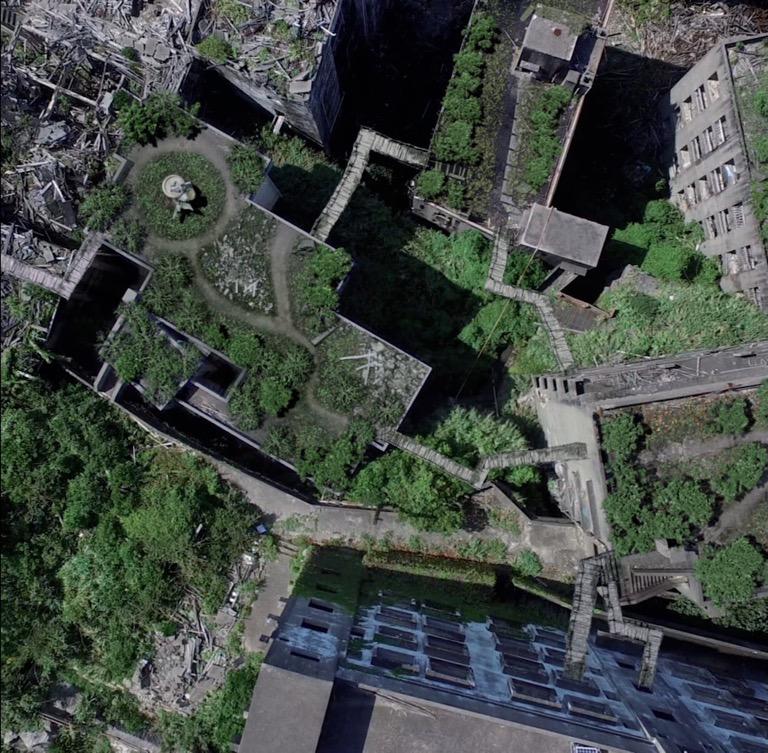

This carpet of moving images, an overwhelming installation, is made up of a vast collection of high-resolution, aerial shots and computer-graphic images of ruins from Japan’s modern industries.

Like parks (neutral spaces in the city,) these are also limited spaces that emerged from industrial production during the modern era. To compare the two, we surveyed and made a video record of these industrial ruins built under the modernization, whose function came to an abrupt end due to changing times. In light of the fact that enclosed spaces and functions were also segregated in the Western Industrial Revolution, one might say modern industrial relics and parks have a yinyang relationship. A special effort was made to observe the present form of the relics by focusing on detailed areas that have been revegetated and eroded by nature.

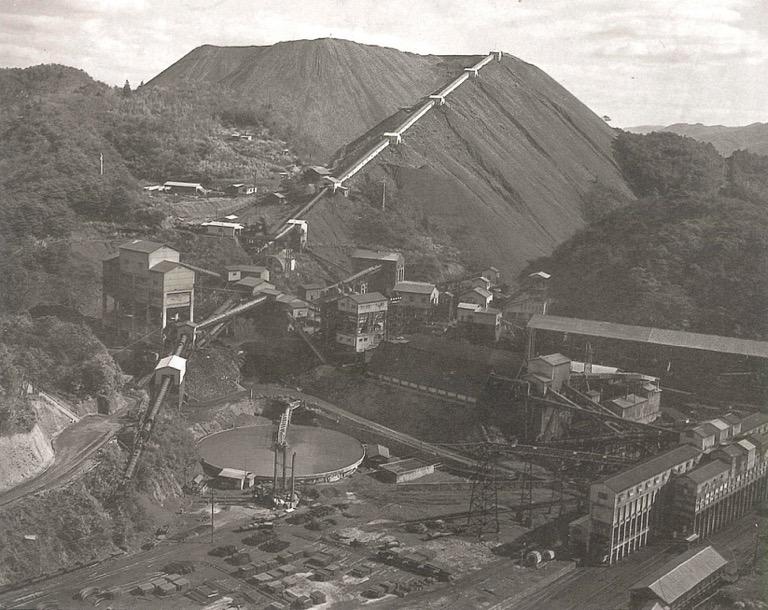

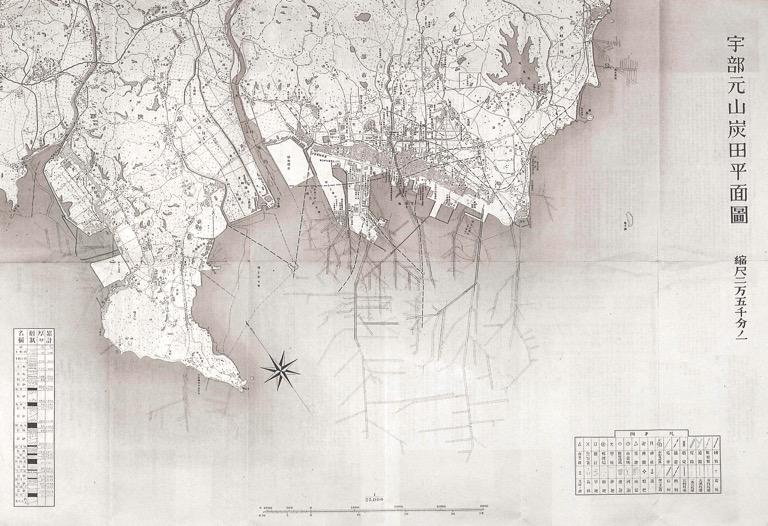

The production of the installation began with an investigation of ruins (relics of early modern industry) in Yamaguchi Prefecture and the Kyushu region. Thanks to their geology, Yamaguchi Prefecture and the Kyushu region were endowed with mineral resources, so they prospered on the back of the wave of modernization during the Meiji period and high postwar economic growth in the 20th century. The sites of many mines from which coal and other minerals were extracted can still be seen today.

The research team made a list of these industrial relics and, as they visited each one, they encountered the reality of how most ruins are gradually torn down after reaching a certain level of decrepitude. Finally, they selected four of Yamaguchi Prefecture’s key remaining ruins and recorded them as symbolic relics, along with Gunkanjima, a relic of early modern industry in Nagasaki Prefecture.

- Ogori Water Works (1923 - postwar period [exact date unknown]):

Yamaguchi City, Yamaguchi Prefecture.

Remains of the municipal water works - Kawayama Mine (1658 - 1971):

Iwakuni City, Yamaguchi Prefecture.

Remains of a mine (copper, iron sulfide, silver, zinc) - Gunkanjima (Hashima Island, 1810 - 1974):

Nagasaki City, Nagasaki

Prefecture. Remains of a submarine coal field - Sanyo Anthracite Mine Facility (1877 - 1971)

Mine City, Yamaguchi Prefecture.

Remains of a coal mine - Chosei Coal Mine (1914 - 1942)

Ube City, Yamaguchi Prefecture.

Remains of a submarine coal field

Some of these mines had been in use since before Japan began to modernize; as mass production grew with the development of heavy industry in the process of modernization, most saw their prosperity peak. However, against the backdrop of a shift from coal to petroleum as a source of energy, not to mention various terrible accidents, these mines ceased to have a role and they fell into ruin. One of the factors behind the construction of the dam to supply tap water to Ogori was the expansion of its urban functions due to modernization during the Meiji period. This expansion in urban functions triggered a population explosion that necessitated the development of a water supply system to prevent the spread of epidemics. Sometime after the war, the need for modern water supply facilities resulted in the dam falling into ruin. These ruins exist in urban spaces as entities cut off from the current passage of time and bear a kind of pattern, in the form of the degradation or revegetation of these manmade structures. Properly speaking, a pattern is a regularly repeated motif; for people, the patterns of these ruins call to mind the passage of time as it repeats and changes, while simultaneously offering a glimpse of how the passage of time will affect our current urban spaces in the future.

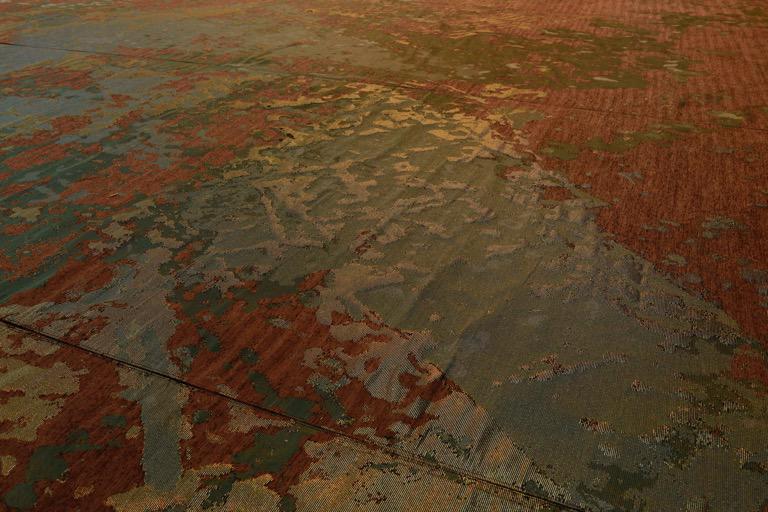

Woven Carpet

Based on aerial video footage of four symbolic ruins in Yamaguchi and Kyushu, MOON Kyungwon created a pattern formed from a collage of elements from the ruins and used Nishijin weaving techniques to weave these into a massive carpet. The carpet grew in size over the course of the exhibition, eventually covering the entire floor of the exhibition space. The carpet into which the pattern of ruins was woven organically transformed the boundaries as it grew to fill the space, presenting a sense of continuity and endlessness.

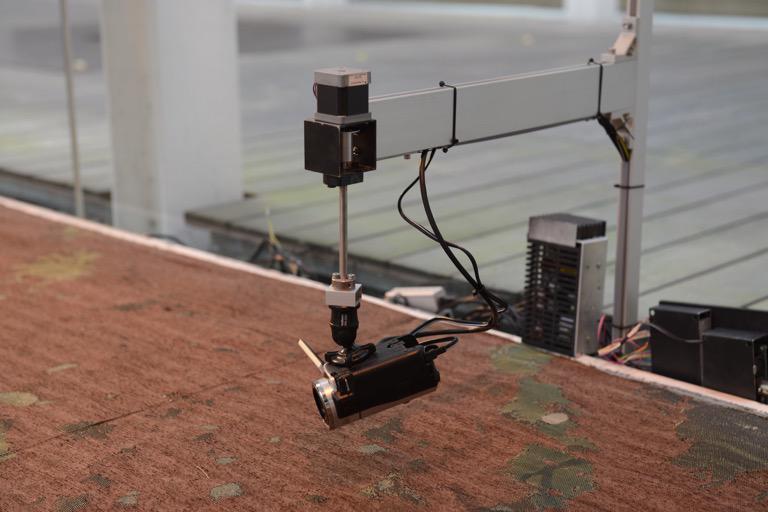

The gold leaf woven into it using a distinctive Nishijin technique combine with subtle variations in the computer-controlled LED lighting to alter the carpet’s hue from one moment to the next. The color of the lighting changes based on data from outdoor light sensors. Four monitors have been installed above the carpet, repeatedly showing video images of ruins, a loom, and the carpet. A computer program breaks these video images down like the warp and weft of a textile and weaves them together again on the screen. This shows Shukuchi (folding space) and the process by which the carpet’s pattern was generated and woven. The video images of the carpet are shot in real time using a camera attached to a robotic arm. Influenced by changes in the light outdoors and the indoor lighting, the camera captures details from the carpet. The movement of the robotic arm makes the camera pan slowly across, causing a landscape to emerge from the design of the carpet, the appearance of the materials, and the structure of the weave, which is then displayed on the monitor screens. Sound is provided in a multichannel surround sound environment, using field recordings taken at the ruins. Two parametric speakers bring voices raining down along with the spotlights. The voices are the collected memories of people associated with the park; they gradually appear and disappear with the spotlights as viewers move around.

A multi-channel sound installation was installed in the patio linked seamlessly to the carpet. The sound of a loom actually weaving textiles was recorded and Dalparan (musician) composed for multi-channel speakers installed under the floor to make the sound of the loom seem like tiny insects.

Related article

Interview with Ken Furudate

Carpet of Moving Images

A park of the future, perched atop computer-generated images of ruins, was depicted on high-definition aerial footage of ruined relics of early modern industry filmed by MOON Kyungwon with a drone

Park Atlas: Atlas Formed by Memories of Parks

In this exhibition, guest researcher Rurihiko Hara, a specialist in Japanese gardens, and other researchers, present “Park Atlas” based on the results of surveys related to the lineage of parks of the past which were conducted in conjunction with YCAM InterLab. The atlas approach is used to present two opposing lineages: the Western and Eastern models, the pre- and post-modern, the macro and micro, comprehensive and diffused space as seen in various kinds of parks around the world and Archive of Stones in Yamaguchi City. A huge variety of data, including plans, photographs, videos, paintings, texts, bibliographies, 3DCG are presented using a multi-screen, slideshow format. With this new atlas, it is possible to analyze the evolution of parks in a historical context and to find connections, changes, and sudden leaps between various elements.

- Modern Parks:

- Hyde Park (London)

- Central Park (New York)

- Ueno Park (Tokyo)

- New Developments in the Park Concept:

- Mundaneum (Brussels, Geneva, Mons)

- Garden in Movement, Parc André Citroën (Paris)

- Yamaguchi Central Park (Yamaguchi)

- The Lineage of Park-like Spaces in the Pre-Modern Era:

- Archive of Stones in Yamaguchi City (32 locations)

The Formation and Development of Modern Parks

As case studies, we first examine Hyde Park and Central Park, considered to be the origin of the modern park, and Ueno Park, an example of the concept being imported to Japan. This is followed by new developments in the park concept, such as the Mundaneum, created by Paul Otlet, the socalled “father of documentation,” Parc André Citroën, which contains Garden in Movement, conceived by the French Landscape architect and thinker Gilles Clément, and finally, Yamaguchi Central Park (adjacent to YCAM).

The Lineage of Park-like Spaces as Seen in Constellations of Stones

Though parks are devices that were originally formulated in the modern era, park-like spaces naturally existed long before that. To explore this lineage in Japan, stones ─ which function as a living archive imprinted with various temporal layers that have existed in the city since ancient times ─ provide us with various hints. Due to the fact that stones are characterized by a nearly eternal constancy, they exist as a key component of public space while constantly acquiring and changing significance and function. To more extensively explore the relationship with urban theory in a somewhat unofficial manner, we used the large area of basin surrounding Yamaguchi, the city where YCAM is located, as a subject of analysis. By comparing the entire area to a park, we embarked on various research and fieldwork projects based on stones in 32 locations. Not only do stones have a fetishistic, religious aspect, their connection to the surrounding topography and the positional relation between them can be seen in terms of the sun’s movement, transportation, and economics, giving rise to a multi-tiered, multi-temporal conception of the city.